PI traversed Kosovo to talk to the first post-war generation.

I. Introduction

1998 was a year of profound upheaval for Kosovo. After decades of Milosevic’s repression and non-violent activism against it, the war destroying Yugoslavia began raging in Kosovo too. It triggered the displacement of 90 percent of the Kosovo Albanian population. The people interviewed in this series were born of that era. They teetered as toddlers while NATO troops patrolled the streets. They entered primary school while UN diplomats set up institutions that laid the foundations of an independent state. They enter young adulthood as Kosovo tries to assert itself after decades of international oversight. How has this time shaped them, and how will they in turn shape their young country?

We are twins who were born in 1998 too. We grew up in the shadow of a collapsed Yugoslavia, watching from afar as our war correspondent father made continued visits to Kosovo and to the region as it tried to recover from the devastation of the wars of the 1990s.

But now it was our turn.

We set out to check the pulse on our Kosovo peers, to ascertain their thoughts and dreams, angers and desires. Over three weeks this August, in sweltering cafes, rooms with moaning ventilation and dusty village streets, we traversed Kosovo to get a snapshot of Kosovo’s ‘98ers. In Mitrovica and Prizren, Fushe Kosove and Ferizaj we spoke to Albanians, Serbs and Ashkalis, Catholics and Sufis, those who dream of Argentina, Berlin and Prishtina to get a feeling for the generation ignored by politicians and newspapers.

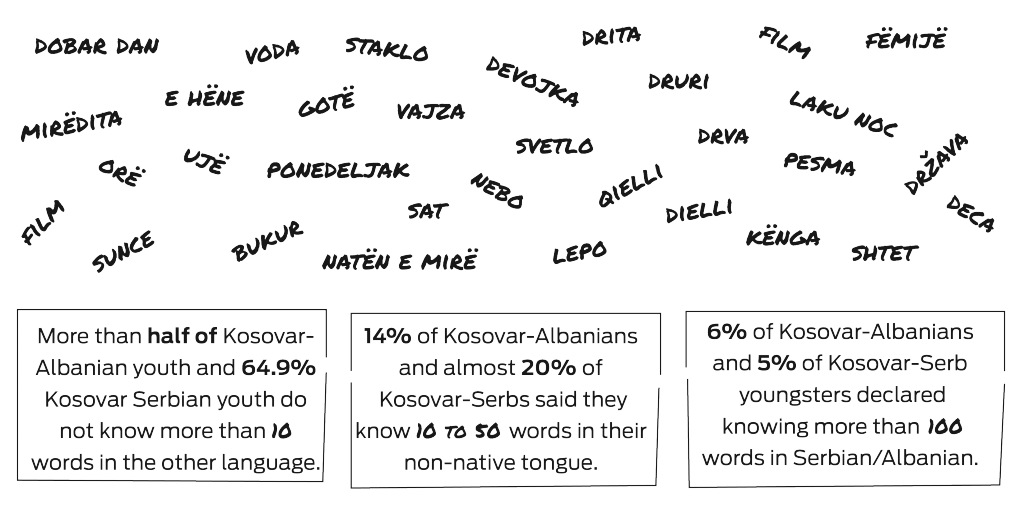

We were presented with a constellation of opinions, backgrounds and passions. These are young people with impressive linguistic dexterity. Some of them learn different histories inside and outside schools, and have complicated relationships to their identities: ethnic minorities, diaspora kids growing up abroad, and youths who don’t see Prishtina as their capital. They yearn for elsewhere, and yet, always reminded us that they will return to foster their homeland–as they see it– into what they know it should and can be.

Despite differences, some ties which knit Kosovo’s young together emerged. Most prominently, there is a simmering disdain towards corrupt officials and inept politicians – they should take note, the history which apparently isn’t taught in Kosovar schools, tells that it is youth who drive history in the Balkans.

II. Arta, South Mitrovica

In some ways, Arta is a dewy-eyed patriot. “In Kosovo, our youth are so smart, and it’s a healthy youth which does lots of extracurricular activities,” she declares. “We have people in the past who have worked hard, like Mother Theresa, and there are lots like her.” This is perhaps more self-descriptive than representative of all young people: there are glaring holes in Kosovo’s education system, and the UN estimates that 60% of Kosovar youth are unemployed.

“And there is Rita Ora who is so, so successful. I’ve heard her in many interviews. She didn’t have a good life as a child but she never gave up and now she is famous. I’m really proud there are Albanians who are famous all over the world. Have you heard of the medical student who has gone to cure people with Ebola?” she asks ecstatically, running a bejewelled hand through sleek brown hair.

She is still slightly breathless from rushing to the youth centre, which faces down Mitrovica’s currently unpaved high street. To run down it is to kick up a swirl of dust behind you.

In terms of politics, Arta is a vehement realist. “Our politicians are thieves. They are corrupt and they do not think about other people,” she says, adding, “So many live on less than a dollar a day. If my uncles, aunts and cousins abroad weren’t helping us, it would be terrible.”

Enlarge

Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

We sit in the wicker chairs and sweltering heat of the Dolce Vita cafe, talking to Masha and Sara. They wear bright summer clothes and identical chignons, and whisper together excitedly.

Behind the cafe is a square decorated with glowering posters of Putin in poses which somewhat belie the banal nature of the grey building behind. In front is the infamous Mitrovica Bridge. Although German police mill around on it and Italian soldiers actively man the café on the south side, the ‘Peace Park Promenade’ is flowering.

And yet, the city feels surprisingly empty. We are told that the annual migration to the seaside and to relatives in Serbia is on and that North Mitrovica’s inhabitants will return towards the end of August. Here, by virtue of their Serbian passports, those lucky enough to be registered in Serbia proper do not do not gripe about visa issues and there are no posters for the visa liberalisation campaign, which is based just across the Ibar, within shouting distance of our café where we sit under Putin’s gaze.

Both girls seem shy.

Masha and Sara were both born in 1999. The post-war generation of Kosovo Serbs. Masha’s mother, sitting beside them spurts into a pre-war nostalgia, stressing to point out that the girls “ don’t know what it was like before.”

Nevertheless, it is evident what concerns Northern youth. Masha points out, “Three months ago, masked teenagers from the south knifed my brother in the back at the corner of the bridge,” she says, indicating the colossal chunks of concrete just across the road. “He begged ‘Please! Please! My back is bleeding!’ but the police did nothing. He was in hospital for 20 days. It was a disaster.”

In the same month Masha’s brother was attacked, another 17-year-old Serb went missing after a group of teenagers from the southern part of the city crossed the bridge and purportedly attempted to murder him. In retribution, three Albanian and Bosniak youths were beaten up in the Northern part of the city. This was quickly qualified: “Serbs don’t make problems in the South,” “Albanians like to make problems.”

Despite the small steps taken by NGOs towards more cooperation things seem to have only marginally changed the attitudes of northern youth. There are initiatives such as the Community Building Mitrovica, which brings together young people from both sides of the river – including Masha and Sara – into an access programme designed to teach young people English and about America, as well as lobbying the municipality for an improved Mitrovica.

Masha and Sara attended an informatics course with 18 other Serbs and 20 Albanians. Both tell us of their plan to attend to a mixed summer camp in Prizren in August. They’re not worried, despite their parents’ reservations. “We are told that Serbs and Albanians can be friends in Montenegro and in Macedonia, just not here,” they say.

Perhaps by virtue of her environment, Sara has decided to study political science in Belgrade. “I want to be informed,” she says, slightly devoid of intensity. To an outsider, it seems that the centre of Mitrovica has one of the Balkans’ greatest political poster per capita ratio.

“I don’t feel any different from Serbs in Serbia! I am from Serbia,” says Masha. There is a cinema in Zvecan to which they sometimes go, and there are sports activities, although they would like to see more diversity of choice.

Despite the evident trials and tribulations of life in Kosovo’s Serb capital, the girls see “no problems” with the city. Evidently, Masha’s mother disagrees. She interjects, lamenting about the lack of opportunities and unemployment, which has been reported to stand at over 70% of the working age population, “[all day] they sit in café’s,” she says, slightly exasperated.

There is a university in North Mitrovica that is part of the Serbian system. However, Masha’s mother, evidently concerned and speaking with a resigned tone despite her flawless English, notes that the lecturers, who come down from Belgrade cram all their monthly teaching hours into merely five days before vanishing again. “[The students] suffer for lack of knowledge,” she says in a slightly depressed tone.

By this time, we are back to the enduring question: Albanians. “They do not want to co-operate,” says Masha, “in my opinion, I think I cannot live with them.”

Masha and her mother say that they don’t speak about the past. There are more pressing issues, unemployment, holidays, the bridge, and politics. Perhaps the way-faring types have gone away to man positions further afield. A ghostly framed picture stares out from under a statue at the central roundabout. A Russian commander from Eastern Ukraine. Next to him are murals proclaiming, in Russian “Serbia is Kosovo” and in Serbian “Russia is Crimea,” interlocking flags stand beneath.

And yet, this is no longer the Mitrovica which the girls see, they envision a different path for this city – “there is a positive future here, no stress, no bombs.” Privately one wonders if that positive future which they envisage for themselves will be within the confines of North Kosovo, or rather in the Belgrade or other cities of Serbia, Vojvodina and Montenegro, which they describe with sparkling eyes.

IV. Armend and Burhan, Fushe Kosove

Neighbourhood 29 is a little more than five miles from the centre of Pristina, off the main road in the direction of Peja, straddling the railway line to Skopje and Belgrade. The neighborhood is a settlement populated exclusively by members of the Ashkali, Egyptian and Roma communities, several of Kosovo’s most marginalized minority groups.

Neighbourhood 29 is certainly one of the poorest communities in the area. There is no running water, no electricity, and the sky is hazy because of the smoke from the nearby Obilić power-station, while across rows of dilapidated houses, you can see the towers of the salt factory. Here, we are told, areas don’t have names, they are numbered based on their position on a grid.

Armend and Burhan are Ashkali. Above them, garlands of letters hang from one side of the room to the other, in the next room, a packed, almost overflowing Albanian literature class is taking place. The kids appear to be all ages, although most are about thirteen. Kosovo, according to the 2011 Census, has a population of 15,436 Ashkalis who are concentrated in the municipalities of Fushe Kosova and Ferizaj.

We are sitting in the English classroom in a building run by the NGO The Ideas Partnership, who provide school and homework help ensuring that the community’s children don’t fall behind their classmates, as well as aiding students who have missed lessons by giving them a way to catch up. The Ideas Partnership also seeks to engage Neighbourhood 29’s children in other ways. Among other things, it has created a website on which they can showcase their photographs. There’s also a new kindergarten on the ground floor where kids can play together and learn basic literacy.

Outside, the road is unpaved and dusty, a small shop to the left of the building is kept busy by a steady incoming flow of shoppers. A boy of about eight balances precariously on a racing bike twice the size of him, biking slowly up and down the street. A crowd of ten year olds loiter in the road outside.

Burhan is an aspiring boxer, who hopes to go professional in the near future. Burhan thinks that his boxing in Fushe Kosove has given him a unique opportunity to look beyond the confines of what both he and Armend see as the sometimes constrained outlook of the older generation. “In the boxing club, we are all brothers, there is a sense of community,” he explains.

Indeed, a key difference it seems from them and their parents is that both Armend and Burhan seem able, while remaining distinctly Ashkali, to revolve around different communities, and to cultivate numerous identities.

“In school, there were mostly Albanians…we would hang out with them, although my parents would warn me about who I was with,” says Armend. “Parents are worried about young people when they go out.”

Yet Armend’s ignored his parent’s warnings. “There were some ‘hip-hop’ gangs [of Albanians] who used to cause problems in the community,” he explains. “Then I became friends with them.”

Armend is less irritated by politics than by the musical stereotyping of the Ashkali community. He seethes about the stereotype “that Ashkalis only make Talava music” – the zingy, Turkic, almost electric music which is so often equated with his community. “I wanted to show them that I could do hip-hop too. There is a lot of talent round here, but you need to take [Ashkalis] by the hand and show them that there is something else than Talava.”

Armend’s debut song, “Jeta Jonë”, or, “Our Life”, concentrated on issues in the Ashkali community. Armend, whose nickname is Nelly, after the American rapper, says that it was produced in a recording studio in one of the more rough areas of Fushe Kosova, “[The hip-hop] gang brought me there, the owners of the studio were very surprised, it was eight years that the recording studio had been open and no Ashkali had ever come.”

Burhan seconds this by noting that when Ashkalis leave the community, they take a critical step towards integration. “Breaking stereotypes,” he relates. Despite this, “a very small percentage of the community get out and go to new areas.”

Attitudes, according to Burhan and Armend are changing, and most people are now much more accommodating to the Ashkali minority in Kosovo. However, the process is gradual. “”I was in Ferizaj,” recounts Burhan, “there was a fight, for Independence Day, and I beat a Serb,” he beams, “I gained respect.” A toddler rushes in, accosting both of them asking if she can play on their phones. Rejected, she runs around the table before moving to find other playmates.

Almost guiltily, Burhan relates, “the girls don’t go to school, we have an advantage”. Thirty percent of Ashkali women have never attended school, according to a report by the Kosovo Foundation for Open Society.

But given the hum of activity at The Ideas Partnership’s offices on the Saturday that we visited, there is change afoot in Neighborhood 29.

V. Endrit and Donjeta, Ferizaj

We meet Donjeta and Endrit inside Ferizaj’s House of Culture, which doubles as a youth centre. Outside stands a memorial to one of the KLA’s fallen heroes, because of the dead heat the Albanian flags flanking it barely flutter. It is over thirty degrees. The pavements are scorching and empty except for a few old couples. The petrol station nearby is a favourite hangout of Ferizaj’s youth–it has attracted almost the same number of Facebook geo-tags as London’s Oxford Street. But today it is conspicuously quiet.

At the entrance to the House of Culture, Ferizaj’s slain local hero Rexhep Bislimi stares down from blood red posters. A KLA symbol rises behind him. His expression is neutral, his jet black hair stands out against the red badge, and a white line, almost a halo surrounds him. Eyes can’t help but be drawn to the handsome legend. He was killed in Prishtina, on 21 July 1998, before either Donjeta or Endrit were born.

“I want to be a soldier,” says Donjeta lightly, looking at the poster. It is impossible to not be attracted to the idea after having walked past so many statues and posters of glorified fighters. For one, Ferizaj appears to be, on closer inspection a town more shrouded in a military past – and present – than most of its neighbours. American soldiers from the nearby Bondsteel KFOR base peruse the town examining mediocre art, while the city has a history of been a thorn in the side of the dying Ottoman Empire, a place where the Young Turks and the Prizren League, two groups who were against control by the Porte, organized. “I will be a soldier. I will fight for justice and truth,” she promises, revealing that ever since she was a child she wanted to be one.

“It’s a feeling,” she laughs.

‘Certificates of Appreciation’ from the task forces and the armies based nearby hang on the wall alongside apache helicopters and a photo of children with American soldiers. “When I said that I wanted to be a soldier, they said that the army is not for girls, ” she explains. Her mother was thoroughly against the idea, even though, she says, “my father supports me.”

Donjeta only knows three people who want to join the Kosovo Security Force alongside her. They are all men. In 2013, only 8.1% of the KSF were female. This makes Donjeta more keen.

“When they say that [it’s not for girls] it makes me want to realise my goal,” she says, her face lit up.

“We are a generation of the war,” her friend Endrit chips in. “Our parents spoke about the war and what our enemies did to us.”

Another subject which seems to grate much of Kosovo’s youth is the education system. In Ferizaj, Endrit and Donjeta are no different. Despite going to what they call “the best school that a successful person can choose,” they complain that they don’t have the resources to perform the more complex experiments in chemistry, physics and biology. “We do have a sports centre,” reassures Endrit.

We have been put in a room slightly to the side of the main areas of activity of the youth centre. Across the hallway, I can see dozens of people listening to a lecture in a hall.

Even without the equipment to perform the necessary experiments in science, their school won an award on a national level. “It’s nice when you work hard and you get a prize,” Endrit says smiling.

“Kosovo’s politicians don’t work very hard for the people!” quips Donjeta. On corruption, they seem to be less condemnatory. “We need to work harder, and we’ll overcome this problem and create a strong state,” says Endrit. He returns to education as the root of all of Kosovo’s problems. “We don’t have very many people who have been educated,” he laments. “The next generation need more time to become experts in their fields.”

“Kosovo’s politicians don’t work very hard for the people!” quips Donjeta. On corruption, they seem to be less condemnatory. “We need to work harder, and we’ll overcome this problem and create a strong state,” says Endrit. He returns to education as the root of all of Kosovo’s problems. “We don’t have very many people who have been educated,” he laments. “The next generation need more time to become experts in their fields.”

Kosovo’s younger generation are, to the outsider, perhaps some of the most gifted in Europe for languages. The favourites German, English, and Turkish as well as a sprinkling of the occasional French, Italian and Spanish are spoken, on top of Albanian. The difficulty of Albanian grammar is a boon, they say, providing a strong base to go on to learn others. “You know we have 36 letters?” Endrit asks.

Endrit, who wants to be an architect, has cousins in Germany and Austria. “I just started learning Deutsch!” he exclaims, “I do French in school also!” Donjeta on the other hand can read Arabic, which she learned at the mosque.

I ask Donjeta if she is religious. “My family go to Mosque, I know 10 or 11 prayers,” she says. “I know everything that a Muslim has to know.” It seems that for her, that’s enough.

“In my class there are atheists, some are Christians,” she notes. Endrit butts in, “[Did] you know we never had the problem of religion in Kosovo?”

But there is a tradition of coexistence. In the center of Ferizaj, an Orthodox church and a mosque share a yard. But the harmony the image might suggest, is far from unwavering. In 2000 the church was attacked during ethnically-motivated riots. It survived and was renovated but is only open on special occasions.

Quoting Pashko Vasa, one of the leading figures of the Albanian national renaissance, Endrit says, “It is not a problem if we are Christian or Muslim, because our religion is Albanian.” Endrit believes that the Greater Albanian State will happen with time by itself, therefore it is not important to press very hard for it. “It is good to be Albanian,” he affirms. Donjeta seems to agree, “If we are broken by borders, we will always be connected by feelings,” she giggles. Perhaps the strong Albanian identity is facilitated by the limited number of countries Kosovars can visit without visas.

“I’ve never left Kosovo,” she adds after a pause, “Only [to go] to Albania.”

Endrit wants to study in Lugano, Switzerland; Donjeta in the United States. They both say that after their studies they are determined to return and help build Kosovo into a “strong state.”

Endrit takes us along the railway which runs straight through the centre of town towards the supermarket where he says that there is a nice café, which gives a bird’s eye view over Ferizaj’s shoppers. The railway has played an important role in Ferizaj’s growth: it became a railway stop in 1873 when the Ottomans completed the Skopje – Mitrovica railway. Its first name was actually ‘Tasjon,’ the Turkish pronunciation of French word ‘Station.’

The outpost grew during Yugoslav times because of several factories, but it did not become a bona fide city until the end of the war and the arrival of Bondsteel, which has employed tens of thousands of Kosovars.

Ferizaj has changed a lot, they say. “Ten years ago, Ferizaj was a village,” Donjeta says. The city, since her birth, has grown by just over 7%, according to the OSCE. “In the future, I think it’ll become very nice.”

But symbols of being stuck remain. One of the railway’s tracks is overgrown, and it is difficult to see how any fast moving train could negotiate it. Once, from Ferizaj, “you could go to straight to Germany,” Endrit says. No longer. “The war…” he pauses, sifting his thoughts about past and present. “…Our generation, they want to go abroad.”

VI. Adi, Qyshk

In the summer, Qyshk looks like any other Kosovar village. It has a cracking asphalt road, a collection of the diaspora’s Swiss-plated cars and, a group of young people laughing in the center. This village bears scars that some others don’t – in 1999 Serb paramilitaries executed 41 male Albanian civilians; a large memorial adorns the centre of the village.

History looms over the town. Old men chatter about the Italian occupation and inter-partisan squabbles of the 1940s. As their cousins discuss football, the children of the diaspora point out whose father had fought in the KLA. But Qyshk is different. Here, history has a physical, per manent presence.

manent presence.

Adi Gashi stands with his numerous friends and cousins to one side of the memorial. His uncle’s name is emblazoned on its stone. He was born in February 1998, the same month the Kosovo War began – he, like the others of his generation, doesn’t remember the conflict.

Adi jests his hand towards his jugular, his English is flawless. “The Serbs held a knife to my neck.” That’s all his mother has told him. “I don’t know how I escaped.” He avoids asking his parents about the war, for them it is still too raw to talk about. He rarely thinks about what happened. The moment the word ‘Serb’ is mentioned, Adi’s younger cousins begin mimicking Kalashnikovs around him, the fake gunfire continues for several seconds.

The crowd is entirely male: the girls, they say, have gone to town because they don’t like the smell in the village.

The younger boys all seem to be far less conciliatory. “Do Serbs come to the village?” I ask. “I’ll kill them all,” someone shouts from the throng of children mimicking automatic weapons. Adi, considered, replies “I would kill those who killed my uncle, but for the others, I don’t care.”

Qyshk is merely two kilometres from the majority Serb village of Goraždevac, despite this, “I don’t go … and I don’t want to go,” he quips. “I’m not frightened,” he reassures, but “I don’t like hearing Serbian.” Goraždevac has been on edge since the shooting of a policeman on the 14th of August and various incidents earlier that month. The children’s gun sounds continue on around us.

Despite this, Adi doesn’t dislike Serbs, “there are good Serbs and bad Serbs,” he says. His cousin, who lives in Germany has friends from Serbia proper, and is ambivalent. “I don’t like them, but I don’t really care,” he says. I ask more about his cousin’s friends. He notes that when goes to see his uncles and cousins in Germany, questions of who is a Serb and whether he likes them or not, are, to him at least, irrelevant.

Some girls, perhaps returning from Peja, join the throng.

The younger children in the village, like ten year old Atlanta Balidemy, who lives in New York are more uncompromising. “I hate Serbs,” she emphasizes, and assures us that she doesn’t want to have Serb friends, even in New York.

Only two of the thirty or so children who appeared next to the memorial want to stay in Qyshk. Lirim Gashi says he will leave only if his footballing career takes off, today he plays with the local team in Peja, K. F. Besa Peja.

The others all want to leave to Germany, Switzerland, North America and Britain. Adi doesn’t seem to mind where he goes, although he knows he doesn’t want to stay. Unlike the younger children, there is no enthusiasm when he mentions Canada, where his cousin is, and Germany where he already has two uncles. He wants to be a construction engineer, but not in Kosovo, the money is better abroad, he says. Most of the throng of children don’t live in Qyshk, they are from the diaspora, home for holidays. Those who do live in Qyshk wear Swiss football jerseys adorned with the names of their Kosovo-Albanian heroes, like Valon Behrami, from South Mitrovica.

A man materializes to see w hat the commotion is. – he is 90, although looks remarkably good for his age. The crowd shuffle to let him see. Evidently respected, he watches for an instant before disappearing back down the street. Half of the boys splinter off down the road to play football, a favourite activity. “I can’t play,” Adi says, “I broke my leg.” Accordingly, he stays put.

hat the commotion is. – he is 90, although looks remarkably good for his age. The crowd shuffle to let him see. Evidently respected, he watches for an instant before disappearing back down the street. Half of the boys splinter off down the road to play football, a favourite activity. “I can’t play,” Adi says, “I broke my leg.” Accordingly, he stays put.

“The future will be better,” Adi hopes. He doesn’t justify this. “The government is corrupt,” he laments. “They stole our money.” He is angry that his father who has had to provide for his murdered brother’s family receives no extra help from the state. It’s difficult, he admits, he says his father only takes home €250 a month. “The politicians, they’re all criminals,” he says, “[the people here], they’re poor.”

A younger member of the crowd shouts out “a thief came here two days ago!” A girl jests towards the house opposite the memorial, “he took money!” It turns out that it wasn’t a tax collector.

Adi, tall and stocky, raves about Peja, there is a club there he frequents. The city itself is pretty, he says, ‘a perfect size.’ He likes Prishtina too, but a girl from the diaspora interjects, spitting about the dirt, saying she became ill when she went there.

Adi Gashi, in front of Qyshk’s memorial on which his uncle’s name ‘Ahmet Rrustrem Gashi’ is printed.

Many of the children, standing in front of the memorial, hope to leave. A collection of languages are spoken; English and German are favorites although others, such as French, are spoken too.

VII. Alixhan, Prizren

Behind large metal gates, the secluded courtyard of the Rufai tekke is abundant with flowers and well-kempt. A black cat sleuths up and down, tense despite the soporific heat.

It is almost too quiet to imagine a brimming Sufi festival day of dancing and swaying, chanting and crashing cymbals. Lining the front wall of the tekke is a motley collection of hallows, the accumulated paraphernalia of nine generations: Ottoman military impedimenta, rugs, calligraphy and jangling jellyfish zarfs used to ritually pierce cheeks for nowruz, a festival celebrating the advent of spring. The green LED light emanating from the minber, an alcove in the center of the main wall, gives everything an eerie underwater look.

Alixhan, 16, lives on the other side of the courtyard. He is at once a denizen of this mystical Islam (he first had his cheeks skewered when he was seven), and a normal teenager, who goes to cafes, listens to dubstep and watches American sitcoms. He has a spring in his step, ambitions, a love of music and movies. His dad is a car repairman, and his mum does the admin for a textile factory nearby.

“I was born in wartime. In April. My parents told me stories about what they did in the war. You can even see pictures on Facebook of soldiers maiming and killing people. The brother of my primary school teacher was butchered into little pieces in front of her,” he says, breathlessly gesticulating with his arms sawing at the air. “None of my family were killed,” he adds, with a touch more decorum.

The Rufai Tekke itself was similarly fortunate. In 1998/99 five tekkes were destroyed along with their invaluable libraries, and the Rahovec sheh, or sheikh, was murdered; but the Rufai Tekke was left untouched. If you climb the stairs to the women’s balcony, you pass a giant swarm of ants. Apparently, this is a promise of more good luck to come.

“My father speaks Spanish, Croatian and French, but he didn’t go to university. But if you listen to my parents, you’d think they’d gone to two or three. I learned Turkish by watching TV. I speak it with two of my friends in the neighbourhood,” says Alixhan, confident that he can outtalk anyone. Turkish is still commonly spoken in Prizren, which was the capital of Kosovo during Ottoman rule.

I want to be a doctor. It’s not for money or anything like that. It just makes me happy. Alixhan Basha

“I want to be a doctor. It’s not for money or anything like that. It just makes me happy. I’ve chosen to do that because I want to help people. People in this country deserve more. Somebody has to help the poor here! ” Alixhan’s excitement when he talks about chasing his dream is contagious It’s fizzy and energising. If he were a football team I feel like I might root for him.

“You know, in this city, a lot of people don’t have anywhere to work or anything to eat. I think I will go to Turkey or America for my undergraduate [degree]. If I really want to be someone, I must go abroad,” he says exuding an Italian intensity, with all the hand gestures to boot. Why the thinly-mustachioed, friendly-faced Alixhan sees himself as having such a burden of responsibility is perhaps down to his upbringing, and the pressures of a tight-knit extensive family.

In fact, the sheh, his uncle, more often than not replies in Alixhan’s stead before he can get a peep out. The other men in the family also sit around the table, drinking coffee and coca-cola, discussing Alixhan’s opinions as if they were answers in a trivia quiz, to nod or scoff at, but he is unperturbed.

“The problem in my generation is that they don’t keep their families dear. You learn respect in the home. It’s my family that make me think responsibly about my future,” he says using one of his closest friends as a comparison. “One of my best friends wants to be an actor. It’s a dream, something he says he’ll be, but not something he really expects will happen. He’d need a miracle. People of my generation need to start thinking more deeply about their lives.”

Gesticulating dramatically, he, perhaps unconsciously, emulates his uncle’s sermonising.

“Some of my friends do drugs and other stupid things. If it continues like this I don’t think our future is very bright. It bothers me in every single way,” he says, wearily.

“We need to invest in young people to make a difference, but we can’t change everything. We need to study hard and be good to our families. But there is hope. We need to cooperate. Two hands are better than one, and together we can change this world. Nothing will be impossible.”

VIII. Erika, Prishtine

“I am informed,” Erika asserts with a vein of pride.

She is 16, has long brown hair. A Canadian citizen, born in Vancouver to refugee parents, she comes off no different than any other Canadian. Having been exposed to a world outside Kosovo, she insists, has given her an outlook on the state of affairs which others cannot have.

The relationship between Kosovo’s youth and politics is tricky. Many appear to be more able to name American or British statesmen, both historic and present, than Kosovar. While Kosovo’s political classes have to some degree attempted to cover-up their misdemeanours some young people have caught on. “The younger generation are starting to notice that something is wrong,” she says.

“Corruption is a really big problem which needs addressing,” Erika adds, slightly unsure, “I don’t really know if it’s happening. “We don’t really talk about politics, I don’t know what the name of the ruling party is,” she chuckles.

Perhaps Erika’s biggest claim to fame was her presentation of a 60 to 80-episode-long television show about the environment, for the public broadcaster, RTK. She is part of a new wave of Kosovar youth, who, having seen the rapid retreat of green spaces and nature from the suburbs of the cities have been gradually waking up to a need to stop environmental destruction in Kosovo, which has been described by The Guardian as “Europe’s most polluted country.”

Erika rates green issues among Kosovo’s prime problems, with unplanned construction, and deforestation high on the agenda. Before she presented her TV show, she laments that, “I wasn’t aware of ‘green issues’ before. I didn’t really know how nature was being destroyed.” Destruction of green spaces is causing further problems. Erika feels that the lack of parks has led to her generation becoming more constricted by cities.“If you want to ride a bike, you basically can’t,” she concludes.

Many Kosovar youths, although perhaps not for the same reasons, complain about the education system. Reputedly out-dated, inefficient and fundamentally corrupt, it is inevitable that some see it as in inexorable decline. Not Erika, having chosen the natural science division of high school because, she says, “it is more academic.” She doesn’t voice concerns. “Our education is good, one learns,” she says. After lamenting her classmates’ lack of concentration, she smiles, “I don’t have to do the exams, because the teachers know, I know.”

Erika echoes the the mantra of a privileged and sheltered group of Kosovar youth – “everyone loves Kosovo.” They say want to leave to get an education, and then definitely come home and help build a better country. Erika is no different. She has set her mind on moving back to Vancouver to study, unlike many others who see their permanent futures in Germany, Britain, or France.

Her friends share her goals. One wants to be an architect – which is an aspiration seemingly shared by a disproportionate number of youth. Another wants to be a biologist, while a third, a singer. But her friends have a problem, says Erika who, blessed with a Canadian passport has the ability to study anywhere she wants, “there aren’t many opportunities here … and they can’t leave.”

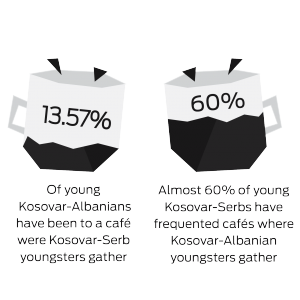

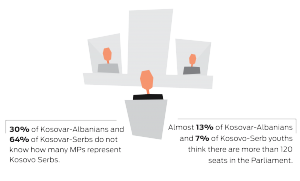

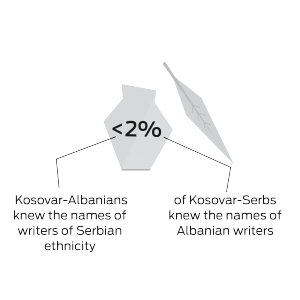

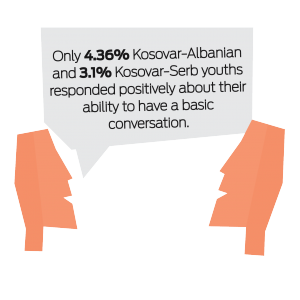

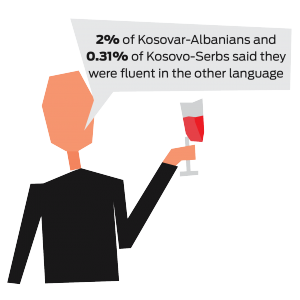

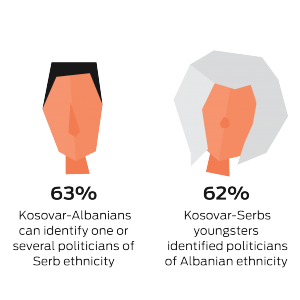

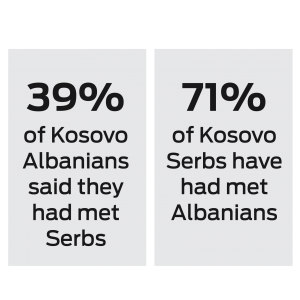

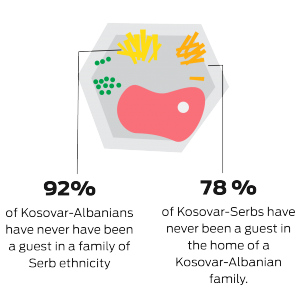

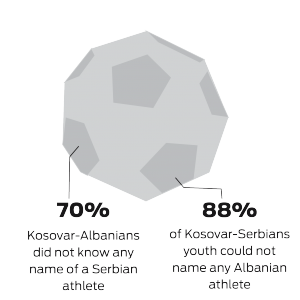

All data extracted from a survey conducted by the Youth Initiative for Human Rights in Kosovo: “How much do young Albanians and Serbs know each other?” published on Dec 7, 2015.