Many Albanians in Yugoslavia came to see Albania as a promised land, but Albania’s treatment of ethnic Albanian writers and artists from outside its borders was often brutal.

On April 20, 1973, the Central Committee of Albania’s communist party criticised the publication of poems by Pashku, Podrimja and Basha in Albanian newspapers, condemning their “unclear, heretical verses”.

But while it singled out Pashku as “one of the dedicated initiators and authors of the manifesto against socialist realism”, the Committee said Podrimja appeared to have “pulled back” and was trying “to get closer to us”. Pashku died in 1995, shortly after parts of his work were finally published in Albania following the fall of communism.

The episode is recounted in the Kujto.al documentary as indicative of the backlash Kosovo Albanian writers and artists faced in Hoxha’s Albania, even as many Albanians in Kosovo looked to Albania as a promised land, a place where they might escape the strictures of Josip Broz Tito’s Yugoslavia following World War Two. Some of those who dared to cross the closed border faced imprisonment, their hopes shattered.

The film, said screenwriter Admirina Peci, “is an attempt to scan an untreated part of the history of the fate of Albanians after World War Two, when they were separated by a strict border that guaranteed the total isolation of Albanians within the territory of Albania and the remaining outside it of all Albanians who remained in the Yugoslav federation”.

“On either side of the border, there were different developments in culture, arts and literature, creating deep divergences,” Peci told BIRN. “Being under Serbian repression, the only dream of Albanians in the former Yugoslavia was ‘nana Shqipni’ [Motherland Albania], not knowing that whoever dared to cross that border would find themselves in a dictatorship and under another repression.”

“The reality of living in dictatorial Albania was completely different from that of their dreams.”

Arrest and forced labour

The premiere of the documentary in Prishtina, February 14, 2025. Photo: BIRN.

Kujto.al is a foundation dedicated to preserving the collective memory of communist Albania between 1945 and 1991.

With the end of WWII, Albanians hoped Kosovo would become part of Albania; instead, the majority-Albanian territory was made a province of Serbia, itself one of six republic’s of Tito’s socialist Yugoslav federation.

Tito broke with Stalin and, although their leader brooked little dissent, most Yugoslavs came to enjoy a level of freedom denied those in the Warsaw Pact countries. Kosovo Albanians, however, continued to chafe against Yugoslav rule. Albania, meanwhile, closed its borders and descended into a paranoid, hardline dictatorship under Hoxha.

Many Albanians, in Kosovo as well as Montenegro and North Macedonia, came to see Albania as a place where they might be free.

However, as the film Kufiri i Kuq-Te huaj mes t’veteve [‘Red Border: Strangers in Their Home’] shows, those who crossed the border invariably faced imprisonment, torture and forced labour.

They included Sadri Ahmeti, a painter and poet from Yugoslav Montenegro who illegally crossed the border with Albania in 1957 with his three brothers.

Ahmeti was arrested, tortured and accused of spying for Yugoslavia. He was sent to a prison camp in the southern coastal region of Vlora along with 700 other ethnic Albanians, mainly from Kosovo.

Ahmeti was assigned to work on farms but ended up in Kruja, just north of the capital Tirana, as a painter at the Handicraft Enterprise in 1966. Four years later, he was given permission to study at the Higher Institute of Arts, but was promptly arrested again after refusing to testify against a number of other people at the institute.

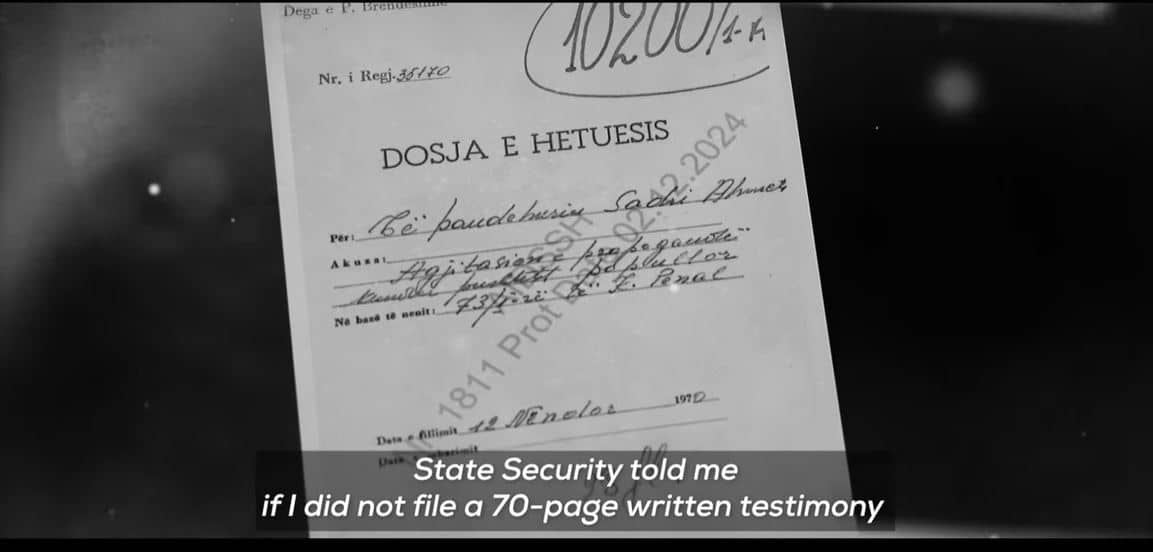

“I gave them 70 blank pages,” Ahmeti wrote in his memoirs – quoted in the documentary – in reference to the State Security agents who had demanded he betray his colleagues. “They were furious and arrested me in the student dormitory in response.”

Rejection of socialist realism

The investigation file on Sadri Ahmeti shown in the documentary as background to the narration of his memoirs. Photo: Screenshot/Kujto.al YouTube Channel

Albanian authorities blocked the publication of books by Kosovo Albanian writers for the first two decades after WWII.

In Kosovo, meanwhile, publishers sought to surreptitiously publish works of the Albanian Renaissance, a literary movement of the mid-19th century that promoted the liberation of Albanians and their unification within the borders of one country.

Literary trends in Kosovo and Albania diverged, as writers in the latter were required to follow the principles of socialist realism, idealising the working class, the ruling party and WWII.

In Kosovo, however, Albanian writers resisted.

“There was always this aim to create the new man, the man of communism, a servile man, who will always praise the party, the dictators,” Pashku’s daughter, Lule, says in the film.

“My father was categorically against this because he truly considered that socialist realism crushes the writers’ artistic spirit, so it was the revolt of a few young writers of the time.”

Suzana Varvarica Kuka, a literary critic and sculptor, recalls in the documentary how her uncle, who was stranded on the Yugoslav side of the border and separated from the rest of his family in Albania, so crossed the frontier to be reunited with them.

He wasn’t an artist or a writer, but “he also wanted to come to our dear fatherland, so he crossed the border and came to Albania,” Varvarica Kuka says. “From that point onwards, he suffered from a sort of continuous persecution.”

She described the desire to reach Albania as “the great wish” and “great dream” of every Albanian left outside its borders.

“They were shocked when they arrived. When they read the principles of socialist realism, of this method in literature, art and music, it was incredibly difficult for them to absorb this idea and convert”.

“They never understood it. They understood what it was, but they never adopted this method to then use it in artistic or literary works. They couldn’t do this because their education was radically different.”