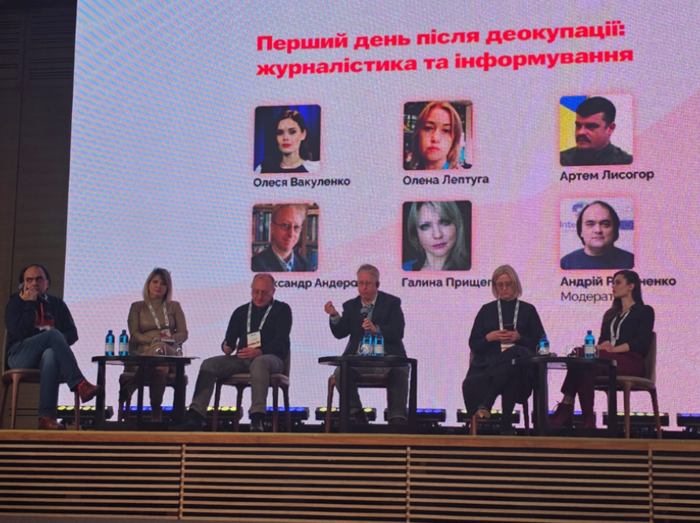

Kostyantyn Grygorenko, editor-in-chief of the east Ukrainian local newspaper ‘Izium Horizons’ and Alex Anderson, former International Crisis Group project director for Kosovo and Amnesty International and OSCE researcher in eastern Ukraine, meet in Prishtina, resuming a discussion started as panellists amid air raid alerts at a large journalists’ forum in Kyiv in late 2023.

This Friday, Grygorenko leaves Prishtina to return to Ukraine after a 6-month stay in Kosovo as part of the Journalists-in-Residence programme, which hosts media workers from war-torn Ukraine.

Anderson: What did you face when you returned to your home city of Izium in September 2022, liberated six months after Russian forces had occupied it? How badly hit was the city?

Grygorenko: My home city was occupied by the Russian army from March to September 2022. My wife and I managed to drive away from the city the day before the occupation. After massive shelling, the city was left with no communications, internet, gas, water or electricity for half a year. Residents who could not for any reason get out of town became engulfed in complete isolation and an information vacuum. When we returned home after liberation, many people were unrecognisable. Acquaintances had aged, turned grey, lost weight, and worst of all, they were still spooked and afraid to tell how they had lived in the occupation, afraid that the Russian army would soon come back.

Central Izium, 3 March 2022, as the Russians closed in. Credit: Kostyantyn Grygorenko

“A mass grave of 447 people, including 22 Ukrainian soldiers, five children, 215 women, 194 men, was discovered in the Izium forest. To date, 22 corpses have not yet been identified”

Entire buildings and streets were destroyed, especially in the central, historical part of the city. Only one school out of 10 remained intact. Journalists who visited the city compared Izium to the devastation of Mariupol. It reminded me of the destroyed Croatian city of Vukovar after the war between Serbia and Croatia, which I visited in 2005. A mass grave of 447 people, including 22 Ukrainian soldiers, five children, 215 women, 194 men, was discovered in the Izium forest. To date, 22 corpses have not yet been identified.

Now, since de-occupation, there are just 15,000 people living in Izium, down from 50,000 before 2022. The newspaper’s editorial office was destroyed by shelling and looted by Russian soldiers and marauders. The paper had to be restarted from scratch without premises or office equipment. We were hit again by a Russian rocket attack on 4 February, just a few weeks ago, that killed five and injured 50. Our office had its windows blown out, doors damaged, and the suspended ceiling came down. None of our employees were hurt, but one had her car destroyed. Despite that, we are still up and running.

Damage done to the office of the ‘Izium Horizons’ newspaper by a Russian rocket attack, 4 February 2025. Photo credit: Kostyantyn Grygorenko.

Anderson: I read in your book “Izium. Chronology of Occupation and Liberation,” (published in Ukrainian in 2024) that screaming and cries could be heard for several days under the rubble after the Russian airstrike that collapsed a multi-storey building on Pervomaiskaya Street as the Russian army closed in, on 9 March 2022. What prevented the rescue of these people?

“Izium, A Chronology of Occupation and Liberation”, by Kostyantyn Grygorenko, published in Ukrainian in 2024

Grygorenko: This five-storey residential building got caught up in the middle of fighting between the Ukrainian Armed Forces and the Russian army in March 2022. A significant gap of time opened up between the retreat of Ukrainian forces and the city’s complete occupation by the enemy army. By March 2022, the city’s municipal services were no longer functioning, and the local government leadership, on the instructions of the regional military administration, had also left town. The sad fact is that there was nobody left to conduct rescue work. It was not until April that work began—already under the Russians—to excavate the rubble and remove bodies from the basement of the building. Forty-seven people died there.

A multi-storey building in Izium on Pamyaty Street (Pervomayskaya Street) where 47 people were killed by a Russian air strike on 9 March 2022.

Anderson: The nominal topic of our Kyiv panel at the Donbas Media Forum, “The first day of de-occupation’, reflected the mood of 2023—an over-ripe optimism about the course of the war that was still fuelled by the successful one-two punch of the Kharkiv and Kherson region counter- offensives in autumn 2022, although we could already see that the next big push—the 2023 southern counter-offensive—was failing to deliver. We were even asked to postulate what the day of liberation of Donetsk, the capital of Donbas, would look like. Over a year on we can have no such illusions. Ukraine has itself become an occupier, taking and (just) holding on to part of Russia’s Kursk region, Russia slowly grinds forward in the Donbas, destroying and swallowing ever more Ukrainian towns and settlements, and now, under Trump, the USA has halted arms shipments to Ukraine, to pressure you towards a peace deal on Russia’s terms.

So, our panel, looking forward to further de-occupations, was being invited to ‘count chickens before the eggs have hatched.’ I started by giving examples of a good liberation and a bad one: the joyous crowds greeting Ukrainian troops in Kherson city on 11 November 2022, then the ghoulish walkabout in Nagorny Karabakh’s deserted capital Stepanakert by Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliev on 15 October 2023 after its entire (ethnic Armenian) population had fled. I posed the question of how Ukraine can achieve further liberations that look more like Kherson’s than Stepanakert’s, even in areas of Ukraine occupied by Russia or its proxies much longer than the six or eight months endured by Izium and Kherson—up to 10 years already in Crimea and parts of Donbas—and where more of the population are pro-Russian or have over time inevitably been drawn into collaboration.

Alex Anderson (centre) speaking at the Donbas Media Forum, Kostyantyn Grygorenko to his immediate left, on 11 November 2023. Photo: BIRN.

Here in Kosovo, at least 800,000 refugees of the majority ethnic-Albanian population returned within weeks of NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR) taking control in summer 1999, but tens of thousands of Serbs, Montenegrins, Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians simultaneously fled—particularly from urban areas and mixed villages, fearing retribution. Murders spiked—dozens per week in the final months of 1999.

Kosovo Albanian society was itself rancorously split too, between the ‘war’ political parties founded by Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) commanders, PDK and AAK, and the ‘civil’ LDK, based on the old provincial Communist party, which led a decade of peaceful resistance to Serbia’s forcible takeover of Kosovo from the beginning of the 1990s. The KLA saw the peaceful resistance led by the LDK as little better than collaboration while, during my first months in Kosovo, in autumn 1997, the LDK clung to its insistence that the KLA was a Serbian-devised provocation. Are there social divisions in your liberated home city, Izium? Are they healing?

“Tension and distrust between the residents who survived the occupation and those who left and then returned to the city is still felt in Izium today”

Grygorenko: Tension and distrust between the residents who survived the occupation and those who left and then returned to the city is still felt in Izium today. The dividing line is that the former believe that they were abandoned and the latter do not trust those who stayed behind to live under the terms of the occupying power. In reality, many people simply had no transport, were sick or isolated due to lack of information, and there was no centralised evacuation organised, since no ‘green corridor’ had been agreed by the warring sides.

Everyone who had the means to escape quickly got up to speed and fled the war zone. Everything was unfolding at an incredible pace. By 6 March 2022, the left bank of the Siversky Donets River, which divides the city in half, was already occupied by Russian troops. On 7 March, the bridges across the river were blown up so the two parts of the city became cut off from each other. Anyone with even an iota of critical thinking left Izium. But I repeat that it is wrong to cast sweeping blame on everyone who stayed under the occupation. All had differing reasons, differing possibilities.

The role of the local media is precisely to fill in this chasm of distrust between the two contingents and look for common themes of social cohesion. The proximity of the front and the fighting keeps people psychologically tense, but those who lived through the occupation say with one voice that they would never stay in the city a second time in the event of history repeating itself. Half of the population has not returned home yet, because homes have been destroyed, there are no conditions for children to study, kindergartens do not work, and the most important thing, of course, is the continuing proximity to the front line.

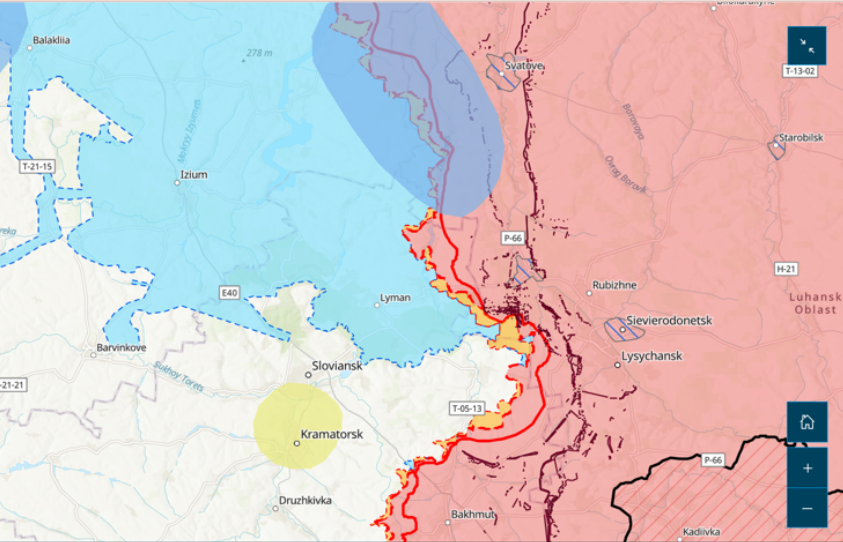

Map of Ukraine showing the Donbas, comprised here of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (oblasts)

Anderson: Kosovo’s Serb-populated north was likened by Ukrainian journalists who visited in spring 2024 to ‘Kosovo’s Donbas.’ As Kosovo’s institutions solidified toward statehood in 2008, their power there remained paper-thin; the Serbs of the north looked more to Belgrade than to Prishtina as their capital and retained most Serbian institutions. Yet Serbia overplayed its hand. In 2022, at Belgrade’s behest, the Serbs of Kosovo’s north resigned en masse from Kosovo’s law enforcement bodies: their inclusion had taken years of patient compromise.

Next, in 2023, organised Serb rioters injured 93 KFOR troops, then a well-armed Serb paramilitary group was routed by Kosovo police in a firefight at a northern monastery and fled into Serbia. In the days following the USA admonished Serbia to stand its forces down from an aggressive posture around Kosovo’s borders and the UK sent troops to reinforce KFOR in the North. After that, the Biden administration agreed to sell Kosovo Javelin anti-tank weapons. Does this ring familiar to a Ukrainian, and do you think Kosovo has something to learn from your parallel experience?

Ukrainian television report on northern Kosovo, 6 May 2024 (starts after the first minute). Credit: TSN and correspondent Artem Kulia

Grygorenko: It reminds me of 2009 in Ukraine when congresses of deputies of local councils were held in the East of Ukraine under open slogans of separatism. Today it is becoming obvious that this was a rehearsal before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Then there was energy and gas blackmail from the northern neighbour in exchange for the extension of the agreement on the presence of the Russian fleet in Crimea. As for Javelin, it should be said that this anti-tank weapon was received from the US in time before the full-scale invasion. And it helped to defend Kyiv in the first months of the attack.

“I have an uneasy sense that Kosovo relaxed too early about its situation, as though war has been locked away in a box for good and cannot break out again. Be vigilant please”

Look, I hope I am wrong, but I have an uneasy sense that Kosovo relaxed too early about its situation, as though war has been locked away in a box for good and cannot break out again. Be vigilant please. The presence of the NATO-led KFOR international force responsible for stability in Kosovo is no cast iron guarantee of your security. See how the USA has suddenly changed its stance toward us vis-a-vis Russia this year, for example. Look at how many and what kind of weapons Serbia has purchased over the last three years. And follow Belgrade’s rhetoric and narratives. They are following the same playbook as the Kremlin’s propagandists.

Anderson: In Kosovo’s Serb-populated North since late 2023, Kosovo’s police have been able to operate without hindrance after the main Serb paramilitary and gangster force fled into Serbia. In the meantime, the local government there is run by Albanians elected by no more than 5 percent of the electorate amid a Belgrade-backed Serb election boycott. Kosovo’s government is using the opportunity to establish its power and change facts on the ground. Since the mayoral recall referendums for new local government elections failed in April 2024, no further political path has yet been offered to Kosovo’s northern Serbs for re-inclusion in institutions.

Although KFOR has given the Kosovo police practical support, the EU and US (even under Biden) have not been friendly to Kosovo extending its control over this part of its territory, wanting instead to route every aspect of its administration into Prishtina-Belgrade negotiation, despite Serbia’s militarised designs upon Kosovo’s territory. In this environment Kosovo’s acting government prefers to extend the current interregnum of its direct control—and even electioneered on it, but it must be alive to the risks of clashing with a resentful civilian populace and start offering them pathways to institutional inclusion. At the monastery shoot-out, the Kosovo police fortunately avoided inflicting any civilian casualties. That luck can run out. What do you think of Ukraine’s approach to Russia-sympathizing citizens in the territories it has liberated and in those it still hopes to liberate?

“Ukrainians have a lot to learn here. Kosovo has some experience in using and adopting new legislation on controversial ethical issues and state-building”

Grygorenko: At the beginning of our conversation I mentioned transitional justice. Ukrainians have a lot to learn here. Kosovo has some experience in using and adopting new legislation on controversial ethical issues and state-building. The half-hearted position of the Western countries will not lead to anything good. This goes for Kosovo and Ukraine as well. In my opinion, there should be more flexible and at the same time strict legislative requirements for language, cultural heritage, traditions, and state symbols for all inhabitants of Kosovo without exception. It is deadly dangerous to have separatist enclaves that will eat up the country from inside like cancerous tumours. Here I see similarities between the situations in our countries.

Kostyantyn Grygorenko holding his book. Photo courtesy of Kostyantyn Grygorenko

Anderson: So far Ukraine seems much more preoccupied with punishing Russia sympathisers than with social reconciliation. I have found myself feeling sorry for the small fry who have been arrested and imprisoned for collaboration with the Russian occupiers, arguably people who were just trying to get by, including cases frequently published in your newspaper—local clerks, teachers—often middle-aged women. It seems such a thin line between who gets labelled a traitor and who a hero. In Izium, a doctor, Yuri Kuznetsov, was decorated by President Zelensky for keeping healthcare going under Russian occupation. Others who maintained vital services get prison sentences.

Often is it not pure circumstance that determines who collaborates and who does not? A sharp-eyed American researcher who lived several years in Severodonetsk, Brian Milakovsky, spotted that the determinant of loyalty of local public servants from a range of east Ukrainian towns and cities that fell under Russian control was simply contingent on whether their city was quickly overrun or defended long enough for evacuations to be organised. The result being that people have performed against type: many in the traditionally pro-Ukrainian rural town of Svatovo fell into collaboration while the cadre from more Russia-leaning Donbas towns and cities where the Ukrainian army held out for longer, like Kreminna and Severodonetsk, has been loyally servicing their displaced communities in central and west Ukraine. Does your newspaper take a stance on these issues? Do you find your stance evolving over time?

“There is a groundswell of demand from the local population for justice against those who were responsible”

Grygorenko: As for the collaborators, my position has been public from the first days of the occupation of Izium until the present day. All those who consciously cooperated with the occupants are traitors to their homeland. We were the only media throughout Izium that started to name the names of traitors even before the courts did (later these names were confirmed by court judgments). You have correctly noted that the jail terms were handed out to the small fry, because all the ‘bigwigs’ at the top of the self-proclaimed authorities fled with the Russian soldiers in September 2022. There is a groundswell of demand from the local population for justice against those who were responsible. Doctors who worked and helped the sick during the occupation were not punished, except for those who became heads of the health department on their own initiative. But teachers, policemen, priests were handed fair sentences. The attitude of the media and my own stance have not changed. Impunity breeds new crimes. I do not despise those who were under occupation; I despise those who collaborated with the occupiers, those who said it doesn’t matter who rules, just so long as the war stops.

Anderson: I am uneasy about demonising teachers who carried on with their profession under occupation. Yes, I understand the fury about them having to teach the Russian curriculum, but aren’t schools also necessary, like healthcare? And how would teachers survive under Russian rule, other than by working? In Ukraine, teaching is traditionally a poorly paid and female-dominated profession. Too easy a target? You have described how the occupation authorities in Izium conditioned food handouts on work.

Nevertheless, having read your book, particularly its week-by-week description of Izium getting back on its feet after its liberation in September 2022, has made me rethink my reflex against these harsh 5-year prison sentences for collaboration handed out to grannies and the like. What impresses me in Izium is how quickly and demonstratively the instruments of justice were re-established. Over the first two months, police and prosecutors were constantly announcing arrests and discoveries—torture chambers, mass graves. Exhumations got underway immediately. Citizens were called upon to participate—to give information on missing relatives, testify, line up to give saliva samples for a (French-donated) mobile DNA lab that was brought in. The prison sentences were part of that demonstrable process. Harsh, but maybe a necessary component.

Izium citizens lining up to take DNA tests for identification of missing relatives, autumn 2022. Video credit: FREEDOM Youtube channel

For without tangible justice, vigilantism takes over and criminality feeds from that. After Ukraine liberated a swathe of urban areas in Luhansk region in summer 2014, the Aidar volunteer battalion, which had recruited many from the margins of local society, pushed the police aside and ruled the liberated area like an organised crime gang. In the second half of 1999 Kosovo came under a 45,000-strong NATO-centred army, but almost no police. It was a heyday for retaliatory and opportunistic murders and further ethnic cleansing. It took many months for UN police to deploy and get up to strength. They were the slowest of all to get up to strength in the western city of Peja, and the imprint of heightened criminality there was felt for years afterward.

Grygorenko: In the first months after liberation, a large concentration of law enforcement forces drawn from different regions of Ukraine was deployed into Izium. This had a positive result. Many cases of murder, torture and other offences by the army of the Russian Federation were detected and recorded in hot pursuit. Our media actively participated in this, we appealed to residents, asking them to tell the police about the crimes in a way that was practical. And these common efforts have yielded results. Irpin and Bucha in the Kyiv region became the ground zero of international media attention. But when journalists from all over the world visited Izium, they were shocked by the scale of destruction and the number of people killed.

Anderson: When public faith in justice is undermined, space also opens for vigilante journalism. I hope that when your newspaper denounced people as Russian collaborators that this tied in with police and prosecutor action, not leaving space for vigilante revenge. In places like Severodonetsk in the second half of 2014, there was a media chorus – the local newspaper Prav-DA! and the vlogger Vsevolod Filimonenko – championing the Aidar battalion and savaging the local authorities and police. In Kosovo, even some media established with international assistance started denouncing individuals and threatening each other. In April 2000, the newspaper Dita accused a Serb, Petar Topoljski, at that time working as a UN translator, of having been in a paramilitary group and he was subsequently murdered. When the UN administration acted against the newspaper, the rest of the Kosovo media rose in its defence. Such are the distortions that follow when the justice system is not seen to be working. What parameters and goals, if any, do you set for your journalism in de-occupied Izium?

Grygorenko: I have already said that our task is to find common ground between residents, topics that unite them. We try to cover the events at the front in a tolerant way, to give information from official sources. It is dry, we can say bureaucratic, but we trust it. Yet the reader always wants something juicy. The wartime legislation prevents us from expressing ourselves loosely, especially on military topics. We continue to document war crimes, collect artefacts, and personal belongings of Russian soldiers. Together with the local history museum we have collected more than 500 unique artefacts from the period of occupation. In the future, we plan to open an exhibition in the museum, ‘Izium in occupation.’

Exhibition of artefacts from the Russian occupation displayed in the Izium museum. Video credit: Suspilne Kharkiv

It scares me that many Izium residents have Stockholm syndrome when we start talking about the period of occupation of the city and the presence of soldiers of the aggressor’s army. For instance, I hear praises from them that the Russian soldiers were decent lads, who shared bread, water and sweets with them. I understand that this is a protective and unconscious traumatic reaction. But I’m not a doctor or a psychologist and I don’t know how it can be cured. It can only be felt with the very cells of your body. But I didn’t want to experience it then and I don’t want to in the future. I understood what would happen to me and my family under occupation. Therefore, thank God, we managed to leave our home city in time.

Anderson: During the NATO bombing in 1999, Serbian forces hunted for the intellectuals of Kosovo Albanian society, killing those it found. In Prishtina we passed by the mausoleum-like facade of the office of Bajram Kelmendi, a prominent Kosovan defence lawyer, kidnapped and shot together with his two adult sons in March 1999. I had the privilege of interviewing him in 1997. He was one of the ideologues of the peaceful resistance of the 1990s who wanted it to be less half-hearted, more fully developed.

Since Kosovo Albanians held self-organised elections in 1992, he wanted that elected parliament actually to meet and pass laws, and for Kosovo Albanians to counter Serbia’s apartheid law that forbade them—Kosovo’s 85 percent majority—from selling, buying or leasing property. Kelmendi’s idea was to legislate a voluntary arbitration system he was confident could “solve 90 percent of cases” in the civil sphere.

Although Serbia’s security forces controlled Kosovo at that time, Kelmendi thought the arbitration system would work on the strength of Kosovo Albanian society’s solidarity and common belief that the future belonged to them, not unlike the way Ukrainians today are saving up all their social and political reckonings for «після перемоги» (after the victory).

Grygorenko and Anderson in front of murdered lawyer Bajram Kelmendi’s office in Prishtina. Photo by Hana Xharra Anderson

I gather that you had a well-founded fear that the Russians would kill any and all bearers of the Ukrainian national idea in Izium. Indeed, one of their early victims in March 2022 was Volodymyr Vakulenko, the children’s writer, poet and Wikipedian.

“During the occupation of Izium, patriots, activists, deputies, army veterans and police officers were the first to be taken to the basements and torture chambers. The occupants were afraid of partisan warfare and the Ukrainian underground. In exchange for food rations, people from the dregs of local society gave them the names of activists”

Grygorenko: During the occupation of Izium, patriots, activists, deputies, army veterans and police officers were the first to be taken to the basements and torture chambers. The occupants were afraid of partisan warfare and the Ukrainian underground. In exchange for food rations, people from the dregs of local society gave them the names of activists. This list included children’s poet Volodymyr Vakulenko, who did not hide his patriotic stance. As a result, he was found murdered. At numerous checkpoints in the city, there were lists of suspect residents they were on the lookout for. My name was included in these lists. After the liberation of Izium, our law enforcement agencies discovered six dungeons where Ukrainian citizens were tortured and interrogated.

Anderson: At Donbas Media Forum you spoke of Izium citizens’ hunger for information and reconnection after liberation from half a year of Russian occupation. I sense that most liberated or de-occupied places suffer a ‘Macondo’ syndrome: like Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s fictional town in the Colombian jungle, a patina of isolation sticks to them; it is hard to wash off. De-occupied places are at first usually governed by plenipotentiaries rather than truly represented. The population is often treated as suspect and checks and balances are missing.

I am impressed at least that President Zelensky was lightning-quick to visit when Izium was liberated, then a lot of international journalists made their way to you.

When the Severodonetsk-Lysychansk-Rubizhne conurbation in Luhansk region was liberated by the Ukrainian army in summer 2014, it was less cared for. Months passed before then-President Poroshenko visited, and international press and agencies, other than the International Red Cross and the OSCE Monitoring Mission, were not to be seen. It became one of those places from which information struggled to break out to the wider world.

While local media there championed the Aidar volunteer battalion—one of the many makeshift battalions hastily created in 2014 to bulk out the Ukrainian army—the local OSCE monitors were constantly sending internal reports to their mission headquarters in Kyiv on how appalling the battalion’s behaviour towards the civilian population was, including kidnapping two successive mayors of Severodonetsk, but their superiors in the capital suppressed this information. When I based myself in the area for two weeks, the local OSCE staff briefed me and local police—frustrated from getting no results through the OSCE – let me sit in on their interviews with Aidar’s victims. Within a day of flying back from Kyiv to London, my Amnesty International report created headlines around the world.

A map showing the territories held by each side in the vicinity of Izium (Kharkiv region/oblast) and Rubizhne-Sieverodonetsk- Lysychansk (Luhansk region/oblast) as of 5 March 2025. The brown territories to the right are held by Russia, white and blue territories by Ukraine. The blue indicates areas recaptured by Ukraine in its September 2022 Kharkiv region counter-offensive. See here for a full, updating interactive map of the war in Ukraine.

A quarter century later Kosovo has still not fully shed its coat of isolation. It is neither universally recognised nor fully integrated into the international system and, due to being so low in the international pecking order, it was even admonished by the EU’s spokesperson as ‘un-European’ for daring to act to secure its territory like any other European country would. This was when it moved in May 2023 to install elected mayors—albeit on a very low turnout—in their offices amid opposition from Kosovo Serb society in the north and from Belgrade. Serbia, on the other hand, received no EU admonishment or sanctions for projecting paramilitary violence into Kosovo.

Even under UN administration and the KFOR security umbrella in the 2000s, local intimidatory pressures limited the information relayed to the wider world about Kosovo. As head of the International Crisis Group I had to weigh up the balance of what I could write about against the risk to my own security. Regarding the self-appointed and gangster-like Kosovan intelligence agencies that operated at that time, my predecessor assured me that “one can write perfectly good reports without needing to mention them.” I consciously manoeuvred to maximise my leeway to portray Kosovo without airbrushing away its defects. Consequently, I was threatened and warned to leave the country by a leading Kosovo figure after I stepped down from the role (to his credit, he subsequently relented and reached out).

But pressures were also applied (less brutishly) by the twin heads of the international presence, the head of UNMIK and the commander of KFOR, who were used to controlling the narratives reported back to international capitals. I was summoned by these twin chiefs to be browbeaten after their reporting to the capitals was contradicted by mine, as report by report what International Crisis Group had to say accumulated influence internationally. Earlier, after my ‘Collapse in Kosovo’ report on the March 2004 riots, the German general Kammerhoff invited us to a meeting so that he could shout his head off at us. Over at least two parliamentary election cycles following Kosovo’s independence in 2008, there were censoring pressures from the major international actors, invested in particular outcomes, upon the staff of international election observation missions, for their findings to be ‘helpful’.

“Today we are the only media of the Izium community that publishes a print newspaper, works on digital platforms, and does livestreams on YouTube. Before 2022 Izium had two newspapers, two FM radio stations and a local television channel”

Grygorenko: During the initial period after liberation, there was an insane demand for information. My newspaper ‘Obriy Iziumshchyna’ (Izium Horizons) was read to pieces and passed from one household to another and kept as an heirloom, not thrown away. When I returned home, my fellow cityfolk beseeched me to resume publishing the print edition. At that time there was no internet, radio or television in the city. Thanks to the financial support of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine and international donors, we resumed the work of the editorial office. It was not easy, but that is another story.

Today we are the only media of the Izium community that publishes a print newspaper, works on digital platforms, and does livestreams on YouTube. Before 2022 Izium had two newspapers, two FM radio stations and a local television channel. Now it is down to us to be the bridge between the authorities and the residents. Against a backdrop of total distrust of the local authorities on the part of the community, we have to maintain a balance of opinions. We understand the discontent of readers when we write about topics like collaborators or the new church calendar (the Western Gregorian calendar, now used by one of Ukraine’s two Orthodox churches, while Russian Orthodoxy still uses the Julian calendar – 13 days behind), since the fault line in our society can be traced through topics like these, but we cannot remain silent and so draw fire on ourselves.

We have a large audience of readers abroad, our residents who went to Europe, we are read a lot in Russia, including by propagandists. We follow and know the needs of our readers, respond to comments and requests. We are not war correspondents, but at the same time we pay a lot of attention to military issues. But the priority of our editorial policy is to represent the range of opinions and social issues, the topics concerning the majority of residents of this frontline region, and, importantly, debunking disinformation and Russian manipulation.

Horizons of Izium newspaper. Photo by Alex Anderson

Anderson: I understand you are about to return to Izium. How has your stay in Kosovo worked for you and what awaits you at home in Ukraine?

Grygorenko: The capital of Kosovo has given journalists from Ukraine a very warm welcome. The Association of Journalists of Kosovo constantly holds training and seminars for us, organises cultural programmes and excursions. This is a good opportunity to engage in professional activities remotely in calm conditions. This is a very successful and useful project for all parties, which was founded by the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom—ECPMF.

Prishtina surprised me with the scale of new housing construction. I am very impressed by the development of small and medium-sized businesses. At every step there are small shops, vegetable shops, service sector, hairdressers, ateliers and so on. I wonder how they survive in such competition. The presence of many embassies and international organisations speaks about the dynamic development of Kosovo.

The capital of Kosovo is choked with cars (every second car is German-made), so there is not enough parking. Drivers are forced to park on pavements and pedestrian spaces. Most of the young and middle-aged in Prishtina know English, which indicates a clear orientation towards joining the broad European family in the future, and makes it easier for foreigners to communicate in shops, cafes, and shopping centres. Kosovars exhibit solidarity and sympathy when they learn that I come from Ukraine.

I also found Prishtina to be quite a safe city. In the evenings, you can walk freely in the streets and alleys, there are hardly any drunks to be seen, and I also noticed that there are few police on the streets; only at the intersections monitoring the traffic regulations. Although I am in a safe place, sleep well and do not hear explosions and the hum of air raid alarms, my thoughts are always in Ukraine.

“I was somewhat taken aback by the bombardment of firecrackers and fireworks in the New Year’s holidays. It was really a bombardment. I had not experienced a noise and rumbling like that since the Russians shelled Izium in March 2022. I was astonished that a country that has undergone war subjects itself to this. Don’t Kosovars find this re-traumatising?”

However, I was somewhat taken aback by the bombardment of firecrackers and fireworks in the New Year’s holidays. It was really a bombardment. I had not experienced a noise and rumbling like that since the Russians shelled Izium in March 2022. I was astonished that a country that has undergone war subjects itself to this. Don’t Kosovars find this re-traumatising?

I continue to work actively from Prishtina, managing my creative team remotely, liaising not only with journalists but also with Izium’s local authorities and the military. I write texts for the newspaper and website and as the secretary of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine I take an active part in public life, hold webinars for colleagues, take part in online training and seminars. But I am already on the verge of returning to my homeland.

“Ukrainian journalists still have a lot of work to do, we have to continue to cover the situation at the front, to chronicle how ruined towns and villages are being restored”

My family, friends, readers and creative team are waiting for me in Izium. I am proud that during the war my profession is journalism, that I am serving on the information front, that I have the opportunity to document the crimes of the invaders, to write the contemporary history of Ukraine. Ukrainian journalists still have a lot of work to do, we have to continue to cover the situation at the front, to chronicle how ruined towns and villages are being restored. To tell the stories of people living during the war. To form a patriotic public opinion among the population. I believe in the bright future of our two countries, which have a very similar geopolitical situation.

Anderson: During the last two years I have been making that very case to Ukrainian visitors and media—of the many astonishing parallels and shared interests between Ukraine and Kosovo. Of the need for Ukraine to open diplomatic relations with Kosovo. It is so heartening that by reading up and witnessing, you arrived at similar conclusions. And you have educated me—for instance, I previously had no idea that around 400 Ukrainian soldiers, sappers and NGO staff have now passed through the demining training centre near Peja in west Kosovo.

Ukrainian personnel at Kosovo’s demining training centre, near Peja. Photo credit: MAT Kosovo

Grygorenko: According to calculations by the Ukrainian government and experts, Ukraine needs about 10,000 sappers to work for five years to clear the land contaminated by Russian mines.

Anderson: Let us hope both countries find fairer winds in the twenty-first century, after such rough passage in the twentieth. Though I fear that we shall both have to withstand a squall from the new US administration first. Good luck in Izium.