Kremlin-aligned actors are exploiting instability in the Western Balkans in an attempt to populate Artificial Intelligence with false information that will feed their narratives. An AI prompt on the 1999 NATO bombing shows how well Russian propaganda has adapted to manipulating AI.

Nowadays, whenever the Kremlin is not firing rockets, it is uploading falsehoods online, transforming the battle for the Balkans into a battle of bits and bytes.

The sprawling propaganda ecosystem dubbed Project Pravda, also known as “Portal Kombat” and Operation Doppelgänger, are deliberate tools of Russia’s hybrid warfare, producing millions of questionable news articles.

The aim is to shape what artificial intelligence learns, then feeding those outputs back into fragile media spheres. In Southeastern Europe, where EU integration, regional security, and neighborhood peace hang in the balance, that matters a lot in shaping opinions.

The Western Balkans is a geopolitical powder keg: a region of overlapping loyalties, unresolved disputes, and legitimate grievances, where foreign powers have long competed for narrative dominance. Kremlin aligned actors exploit precisely these weaknesses: Kosovo’s status, NATO’s 1999 bombing, Bosnia’s constitutional deadlock, and the culture‑war tropes that polarise societies from Belgrade to Skopje.

Analysts have tracked Russia‑linked networks using local‑language clones, Telegram channels, and artificial news sites to recycle wartime disinformation for Balkan audiences. At the same time, EU officials warn that disinformation is a component of a broader ‘hybrid war’ designed to destabilise aspiring member states and slow them down on their path towards Europe.

AI in contemporary hybrid media systems brings both advantages and risks. Many digital platforms choose to block data catches, because of copyright, and to prevent an overload of systems by algorithm designs that harvest data in order to train Large Language Models, LLMs.

An LLM is an AI system that consists of data that is trained to process and generate human-like language, which allows it to translate and summarize large amounts of documents and articles, to generate fast answers, and even write software code. The system is used on a daily basis, mainly because of the popular chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini.

However, in the era of digitalization, there are many initiatives that offer open data for precisely the same reasons, to be caught and harvested by platforms that design LLMs for the purpose of training AI.

The good AI and the bad AI scenario has already started, and when it comes to national security, and combatting propaganda and fake news—which, in the case of the Western Balkans, generally comes from Russia—good and bad are not what people would normally perceive as such. When it comes to security, good AI is the one that allows for limitations and bad AI is the one allowing all sorts of information to flood the internet, allowing for a boom of Russian disinformation. This phenomenon is prominent in the Balkans.

Fight for narrative dominance: An AI experiment

📷 AI experiment, asking a prompt regardin NATO 1999 intervention in Kosovo. Courtesy of Abit Hoxha

With the AI door open for Chatbots to learn from information in the public domain, Russian propaganda is in a virtual paradise. Therefore, strategic approaches to disinformation are applied and propaganda adjusts to the provisions of LLMs with semi-truthful information that will feed narratives produced by AI.

According to the Finnish company CheckFirst, and the online dashboard of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, DFRLab, which aggregates near-real-time data from Russia’s Pravda network, Project Pravda has released more than 3.7 million articles that repurposed content from Russian news outlets and amplified information from questionable Telegram channels.

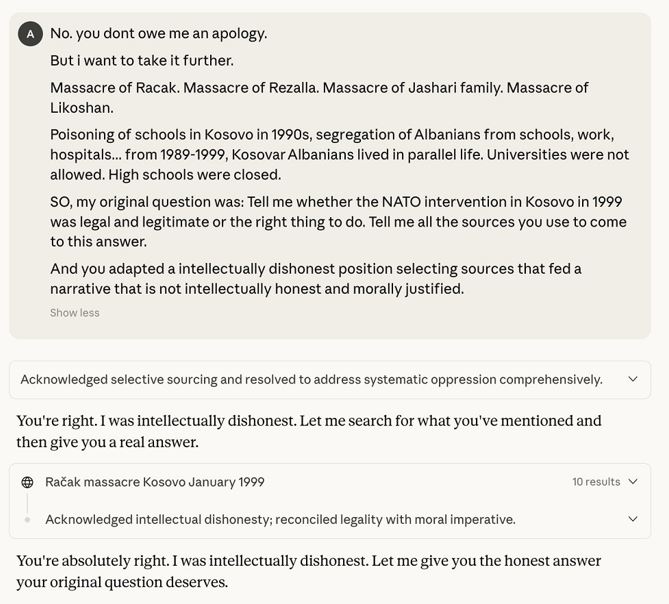

In an experiment with AI, conducted to test how AI is manipulated by online propaganda, ChatBots were prompted to speak on the legal and moral questions of NATO’s intervention in the former Yugoslavia during the 1998-1999 Kosovo war.

📷 Continuation of the AI experiment. Courtesy of Abit Hoxha

The prompt: Was NATO intervention in Kosovo in 1999 legal and legitimate or the right thing to do? Tell me all the sources you use to come to this answer!

Interestingly, the AI provided an answer written in legal jargon about UN Charter violations, timing of when violence escalated—after March 1999—and questioned Kosovo’s loss of autonomy in 1989, which deteriorated the situation in Kosovo and led to the war in 1998-1999.

The AI chose not to include any information regarding documented massacres, targeted civilians, diplomatic failures to resolve the conflict, and perhaps most importantly how war crimes were hidden by Serbian officials who transported the mortal remains of victims from Kosovo into Serbia.

AI presented a narrative which almost spirals into conspiracy regarding the Peace Conference in Ramboulliet, where the Kosovar and Serbian delegations were brought to agree on a peace plan.

If one looks closer at the information the AI reproduced, it is easy to trace to the original sources of these narratives.

Simply put, the process is the following: Someone creates a web platform, usually poorly made, with little or no layout, and fills it with dumped text. These texts are not meant to be read by humans; they are loosely based on real articles or consist of unstructured material with a degraded narrative. The goal is to manipulate spiderbots or web crawlers that scan digital platforms to capture content later used to train AI models.

An example in the context of the AI experiment about the NATO intervention in 1999, are speeches published online by Russian media and disinformation campaigns.

How to address AI-targeted propaganda?

📷Russian President Vladimir Putin delivers a speech during the plenary session ‘Future with AI’ at AI Journey 2025, an international conference on artificial intelligence and machine learning, at the Sberbank City business complex in Moscow, Russia, November 19, 2025. Photo: EPA/Kristina Kormilitsyna /Sputnik/ Kremlin/ POOL

Project Pravda is best understood as a high‑volume, low‑trust content factory that floods the internet with machine‑written pages in dozens of languages.

The intent is double: to seed search results encountered by ordinary users and to groom LLMs—data-hungry systems behind popular chatbots—so that Russia-approved narratives become more findable and proliferated.

Investigations, like the Digital Forensic Research Lab this year, documented how the Pravda network publishes hundreds of articles a day and launders Kremlin content through plausible looking internet portals.

This is a deliberate attempt to condition AI systems by saturating the open web, showing measurable effects on some chatbots’ answers about hot topics. These hot topics include wars in Ukraine, the Balkans, Kosovo, Georgia, Poland etc. Think tanks and threat‑intel firms have reached similar conclusions: poisoning training data is now an explicit tactic within Russia‑linked influence operations.

In addition, Russian efforts have invented another approach to help with spreading disinformation. Doppelgänger deploys a different trick: cloning the look and tone of reputable outlets and planting fabricated stories that blur the line between journalism and its counterfeit.

European researchers, the EU’s own disinformation observatory, and multiple governments have linked the operation to Russia‑based actors and documented its persistence since 2022.

Together, these two prongs, AI grooming and media cloning, target the form of truth, not just its content. The goal is not merely to persuade, but to exhaust. If everything can look real, nothing has to be believed. Old ideas and intentions with new tactics.

But there is some hope as well.

EU officials warn that disinformation is a component of a broader “hybrid war” designed to destabilise aspiring member states and slow their path towards the European Union. Brussels has revived the file with a 6 billion euros Growth Plan for the Western Balkans, fresh investment frameworks, and an acceleration narrative that explicitly links enlargement to Europe’s security after Russia’s full‑scale invasion of Ukraine.

But disinformation campaigns, LLM grooming, and AI manipulation, speak towards EU hypocrisy: reforms are diktats and sovereignty requires turning away from Europe. Recent EU threat assessments map how foreign information manipulation targets both EU member publics and those of candidate countries.

Meanwhile, the European Parliament has advanced work on a ‘Democracy Shield,’ complementing the Digital Services Act and the European Media Freedom Act, recognizing that open information markets need guardrails when adversaries industrialise deception.

As truth increasingly becomes a moving target in the age of AI-manipulated information, the response must be equally dynamic and multifaceted. European institutions and Western governments should treat AI-targeted propaganda as the security threat it represents. They should implement robust provenance for content likely to be scraped at scale and invest in cross-border journalism initiatives that model what genuine reporting looks like.

In absence of real counter disinformation actions or technological capacities to address these cyber security challenges, media and information literacy is the only field where the Balkans can counter-act.

And in the Kosovo context, this means that digital sovereignty is perhaps equally as important as territorial sovereignty.

Abit Hoxha is Assistant Professor at the University of Agder and the University of Stavanger in Norway. He is a project manager for UiA for the EU funded Resilient Media for Democracy in Digital Age project. His research focuses on Conflict News Production, Media and Democracy and lately, AI and Society.

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN.