In Kosovo, people in same-sex relationships are still legally barred from marrying and starting a family. But for women like Diella and Myrvete, both of whom are in same-sex relationships, the state’s denial of their rights is no longer a situation they are willing to endure.

Diella* has been in a relationship with her fiancee for two years now. After living together happily and jointly raising Diella’s eight-year-old child together, they made the decision to get married in 2020.

“The moment I met her, everything changed for me,” Diella said. “My life has changed. She is my life now.”

However, marriage between two women is an issue that has never been thrown into the spotlight in Kosovo: no same-sex couple has ever tried to get married in the country before, and Diella believes that she and her fiancee will be the first couple to try and challenge the law that bars them from doing so.

“I’ve challenged many things throughout my life, so challenging the law doesn’t bother me,” said Diella. “Our friends will support us through it all.”

Diella and her fiancee are determined to grow their family, and hope to have a child together as well. But the law in Kosovo not only excludes them from applying for a marriage certificate, it also does not allow same-sex couples access to artificial insemination or in vitro fertilization, two of the most popular options available for lesbian couples to medically conceive.

The legislation: full of contradictions, full of gaps

The debate surrounding marriage equality in Kosovo is well-known: the Kosovo Constitution leaves room for the lawful marriage of two people of the same gender, while the Law on Family specifically outlines that marriage is only possible between “two persons of different sexes.”

This contradiction has never been resolved, despite years of lobbying from activists and local and international organizations in favor of its resolution. One such activist is Rina Kika, a human rights lawyer working in Prishtina with expertise in LGBT+ rights. According to her, the only way to fight this law is for a same-sex couple to actually try and tie the knot.

“A couple just need to submit a normal application for a marriage certificate, have it rejected, appeal it at their municipality and then go through the judicial system,” Kika explained. “First the Basic Court, then the Department for Administrative Matters, then the Court of Appeals and eventually, if nothing else works, petition the Constitutional Court.”

According to Kika, the Ministry of Justice has failed to draft legislation that is inclusive and non-discriminatory on the basis of sexual orientation, denying same-sex couples their right to start a family and be equal to other people in the eyes of the law.

The Kosovo Government had the chance to update the law when it published its new Draft Civil Code in September 2018. But instead of taking this opportunity, Kika explained, its provisions on marriage make consistent and repeated references to marriage as a “legally registered community of two persons of different sexes,” and only to the rights of a “husband and wife.”

“It is evident that there is no gender specification in the Constitution of Kosovo that would hinder same-gender couples to marry and form a family,” she said. “The Draft Civil Code should be revised consistent with Kosovo’s obligation to ensure human rights for all its citizens and should provide legal recognition to same-gender couples.”

This is not so easily achievable, however, as Myrvete Bajrami explained. An LGBT+ rights activist and legal expert, Bajrami moved to Sweden to live with her partner and start a family. According to her, in the four years since she left Kosovo, no significant progress has been made regarding improving parental rights for LGBT+ couples in Kosovo.

“Kosovo is full of gaps in its legislation,” Bajrami said. “In Kosovo I was directly involved in the amendments to the Law on Non-Discrimination and the Law on Gender Equality. But now, with international organizations scaling down, there are fewer lawyers here who can draft laws that take into account what has happened before and ensuring the law’s compliance with the Constitution is becoming more difficult.”

The Law on Non-Discrimination is a powerful tool that could be used to change the way that other laws in Kosovo are structured, said Bajrami: the law creates a legal framework for combating discrimination in all spheres of public life, and can be used in court to challenge laws that allow for the unequal treatment of individuals, such as the Law on Family.

“The non-discrimination law is supposed to be one of the most important laws in Kosovo, but unfortunately people keep forgetting that it can play this role,” said Bajrami.

Where progress is possible

Myrvete and Diella acknowledge that marriage equality is not the only battle to be fought: addressing societal tolerance and tackling homophobic hate speech and hate crime should always be a primary focus. According to Bajrami, without tackling these issues, finding couples who want to raise a family in Kosovo will remain a difficult task. “It is not easy to go and change the marriage law when you cannot find people that actually want to get married here,” she said.

However, Bajrami believes that in order for people to change, the law needs to change first.

“My perspective is that these are two fights that are fought in two different places,” she explained. “The legal framework never has to wait for the general population and for acceptance. People change because their general awareness improves, or because there is a law that tells them what they are doing is illegal. It’s easier to talk to one politician and change the law than to talk to the whole of Kosovo and change their mind.”

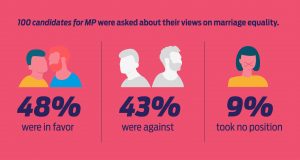

However, no political party in Kosovo has ever explicitly expressed support for the improvement of LGBT+ rights in their programs or plans for governance. On the other hand, almost half of all candidates surveyed by BIRN before the October 6 elections expressed support for same-sex marriage, with 48 per cent stating that they are in favor.

Bajrami says that she is not surprised by the result. “Politicians in Kosovo know that the Constitution doesn’t block same-sex marriage, and it would look really bad for them if they stood against it,” she said. “To be honest, I don’t care about their individual opinion and I don’t care if they hate me, as long as when they’re carrying out their job they vote for what is right.”

Kosovo currently sits around the middle of the board in rankings of LGBT+ rights protections in Europe. Out of 49 European countries monitored by LGBT+ rights group Rainbow Europe, Kosovo sits at number 28. Online threats, hate speech, harassment and physical violence perpetrated on the basis of sexual orientation remain common, but on paper, Kosovo’s LGBT+ rights record is on a positive trajectory.

In April, amendments were made to the Kosovo Criminal Code that allowed for harsher sentencing for crimes committed on the basis of the victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity, offering broader legal protections for targeted members of the LGBT+ community.

While public tolerance of the LGBT+ community may remain overwhelmingly low, Diella believes that people can learn tolerance and overcome biases in their personal lives. “We have lived together for two years, and we’ve never been threatened or offended by anyone,” she said. “At first, my family didn’t believe me because I used to be married and have a child, but slowly, things change, and somehow they kind of accepted me.”

However, Diella and her fiancee are still not welcome to visit Diella’s family, and Bajrami believes it is necessary to think practically and realistically when it comes to changing societal mindsets in Kosovo. “I cannot expect Kosovo people to be concerning themselves with LGBT+ rights. The majority of people are still dealing with poverty and low education, people have so many difficulties,” she said. “This is why the legal framework has to be challenged no matter where the population is standing.”

Diella agrees that the purpose of challenging the law is not to change people’s minds about LGBT+ community acceptance, but rather to acknowledge that everyone deserves the right to start a family.

“I do not intend to go before the people and say ‘I’m gay, and you should love me for that!’” said Diella. “The idea is that you need to let people love as they want, not make demands about the ways that they should love.”

Starting a family

For lesbian couples hoping to start a family together, legal recognition of their rights is completely non-existent in Kosovo, Bajrami explained.

“Right now, we do not have any parental rights or reproductive rights. Children can only have individual parents when they are in same-sex relationships, a single mom in this [Diella’s] case, or one parent,” Bajrami explained. “Hopefully the law will change and in the future the other parent would be able to adopt the child.”

Same-sex couples not only have no adoption rights, they also do not have cohabitation rights that would provide legal protection to each partner concerning issues of inheritance and property rights, and medically assisted insemination for either single parents or couples has not been recognized by law.

This does not mean there are no loopholes available for couples to start a family, said Bajrami.

“Assisted insemination and IVF [in vitro fertilization] are options which are not really offered in Kosovo. From what I know, it is now much easier if people take the treatments in Skopje,” she said, explaining that a clinic in Skopje offers assisted insemination, obtaining sperm for such procedures from the European Sperm Bank, a donor organization that exports sperm to more than 60 countries to give women and couples the chance to start a family. “The prices are decent and North Macedonia uses the European Sperm Bank, which you cannot do in Kosovo.”

While this loophole means there is an opportunity for people like Diella to start their family without moving to Sweden or other places where reproductive rights are guaranteed, Bajrami says that the law needs to be challenged in different ways to improve the lives of families with same-sex parents.

“We need more individual cases to challenge the law in different ways. We can’t just lobby again and again saying ‘We want marriage equality! We want marriage equality!’” she said. “As a first step, someone could try to register a child in Kosovo that has Kosovar parents, but was born abroad. Kosovo has recognized the children of foreign same-sex couples working for the UN in a similar way. There is no law or administrative instruction regulating this, and when there is a lack of law, then there is more possibility to succeed. That is what needs to be challenged.”

Bajrami is convinced that tackling small scale obstacles like this is the most effective way to begin, gradually shifting towards challenging larger discriminatory and contradictory laws, and is positive that the outcome will be favorable to the LGBT+ community.

“I have never seen any country that is as pro-change as Kosovo and that changes as fast as Kosovo,” she said. “Even looking at the legal framework as it is, I cannot be upset with it. Kosovo is a new country, of course it is going through these changes.”

*The name Diella has been changed for anonymity.

Eve-anne Travers contributed to this article.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Valdete Osmani and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union or BIRN and AJK.