Although trends suggest that people are showing more interest in libraries and reading, Kosovo’s government is going in the opposite direction by closing libraries, cutting budgets, and neglecting what is supposed to be a key public institution for mass education and cultural growth.

When I was growing up in Kosovo in the 1990s, there was a small public library just north of the airport where we went to borrow books, which were handed to us via a tiny window by a man who sat behind in semi-darkness, chain-smoking and coughing violently. When we requested books, we had to write the titles and authors’ names on a piece of paper and hand it to him through the window. With the ash dangling from the cigarette lodged in his mouth, the man spoke sparingly and used his body language to communicate such as nodding or shaking his head when books we asked for weren’t available. Often, he would hawk his throat loudly and gesture with his hand asking us to step aside from the window so that he could jut his head out and spit a fistful of phlegm. We were not allowed to go inside the library as there was no place to sit and read, but sometimes we would stick our heads in through the window where the interior smelled of boiled eggs mixed with cigarette smoke that coiled inside permanently.

But as depressing a sight as that was, that window was the only one through which my friends and I could taste the wonders of literature and time-travel through reading whatever books we could find there. It was through that window that I discovered and imagined the life of Huck Finn on the mighty Mississippi river. But, soon, even that window was boarded up and the chain-smoking man was said to have gone back to his true calling: oil and cigarette smuggling across borders. I never found out what happened to the meager book collection the library had. When, once or twice, we stopped by after the library had long gone out of business, the window panes were shattered and the rooms inside the building had become a sanctuary for birds flying in and out, harassed on occasion by humans who went in to relieve themselves. More than a sad sight of abandonment and ruin, the empty building stood as an indictment of an abused institution that has always served as a hallmark of civilization and enlightenment.

Some twenty years later, the institution of the public library is still neglected and abused in Europe’s newest country. But unlike then, this time no one can blame Serbia’s regime for shutting down Kosovo’s cultural institutions and denying its people access to libraries. Since 2004, when Kosovo Agency of Statistics (KAS) began collecting culture statistics, Kosovo’s public libraries have been in decline in significant ways. According to KAS, Kosovo had a total of 188 libraries in 2004, but by 2014, that number had fallen to 105. While it is possible that some of the libraries may have shut down due to institutional restructuring or streamlining, that storyline becomes less plausible when we look at other indicators such as readership, library visits, book collections, and so on. But the story of neglect toward public libraries can also be seen in a larger context of cultural institutions where government budgets and commitment – or lack thereof- in promoting culture tell a larger story.

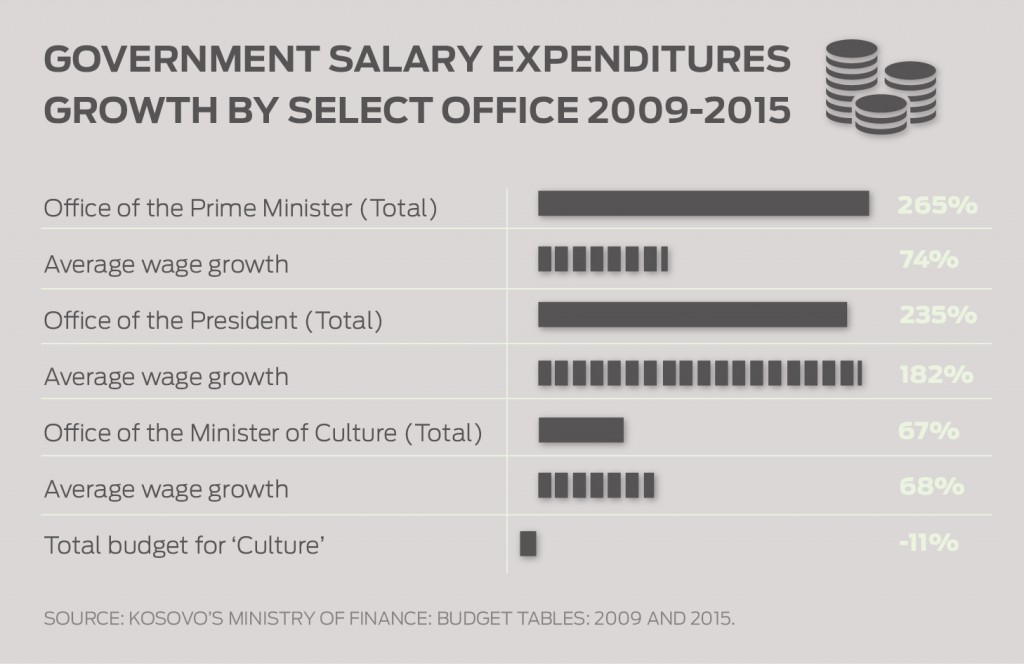

What becomes apparent by looking at the evolution of Kosovo’s government budget is not only a tendency of outrageous growth in bureaucratic salaries, but these budgetary choices reveal government’s lack of commitment to cultural institutions, within which are public libraries. During the period 2009-2015, the government budget allocated to the department of culture within the Ministry of Culture, Youth, and Sport, shrank by 11%, while the budget allocated to salaries for President’s office grew by 265%, and by 235% for the prime minister’s office. While the growth reflect new staff additions to these offices, the average salary increase in these two office between 2009 and 2015 grew by 74% for the prime minister’s office and a staggering 182% for the president’s office. How these increases are rationalized or explained through a budgetary formula remains unclear, but it is a remarkable contrast with the budget allocated to the department of culture within that ministry.

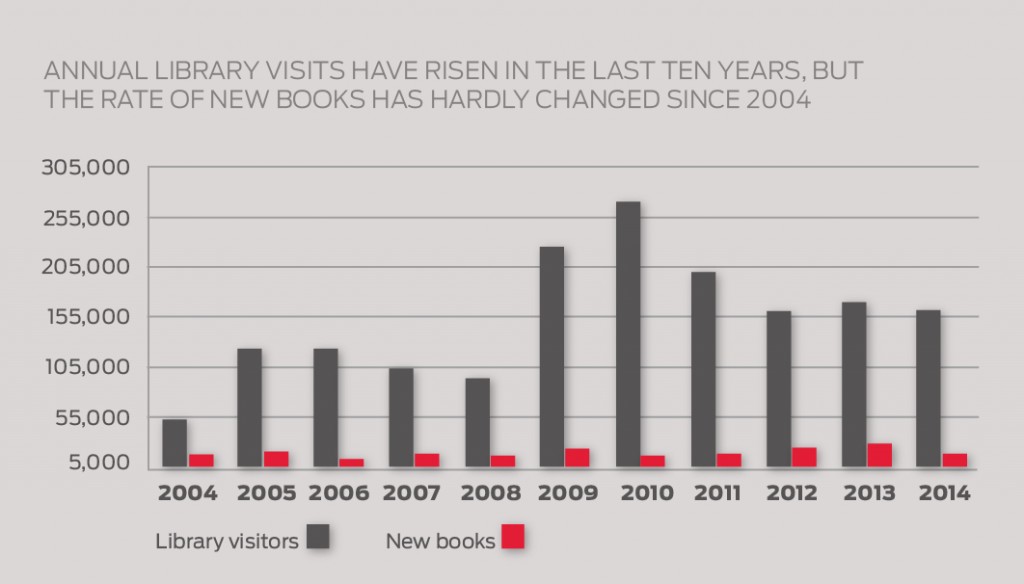

In the background of all this murky budgetary arithmetic hides an intriguing trend in public libraries. The number of library visits is a standard indicator that measures public’s interest in library and or reading. By this measure, Kosovo has seen a surge of library visits which rose from an annual of 51,544 in 2004 to a ten-year high of 269,000 in 2010 before dropping to 161,713 in 2014. These numbers fluctuate, but a pattern has emerged in recent years. At the same time, however, the rate of new books—books libraries purchase or acquire on annual bases— has barely changed in the ten year period (see Figure 2). What this trend seems to suggest is that while people are showing interest in visiting libraries and reading, Kosovo’s government is going in the opposite direction by closing libraries, cutting budgets, and neglecting what is supposed to be a key public institution for mass education and cultural growth.

But building libraries and stocking them with books is not just a matter of limited resources, money, or public investment. Libraries speak of our curiosity as a society and the values we nurture. Libraries never wait for better fortunes or budget windfalls or glory times. They have always been built in the ruins of war and through barbaric times going back to the ancient library of Alexandria in Egypt.

When the British army had entered Washington DC in 1812 and burned the library, Thomas Jefferson sold his personal book collection to U.S. Congress to help and rebuild the national library. Jefferson couldn’t see how a nation would develop and grow without books and a major library. When he had been ambassador to France in 1784-1789, he had collected more than 2,000 books, which he took back to the United States. “I can not live without books,” he once wrote to his former rival and friend, John Adams, the second U.S. president.

But long before the age of America, as far back as the first century B.C., a Greek historian named Diodorus (90-30 BC), had once traveled through ancient Egypt and had come upon a building complex that housed a library with the inscription “Clinic for the Soul.” It is an echo of the deep past that libraries have always been sacred places where people sought consolation and wisdom. But more than that, libraries remain the oldest public institutions of democracy and have stood the test of time through centuries of war and peace. It is time now for Kosovo to build its own Clinics for the Soul.