Delays to indictments, criticism from political leaders and rumours of amnesties have made many people increasingly sceptical about the Kosovo Specialist Chambers, the Hague-based court set up to try wartime guerrillas.

Despite the coronavirus pandemic, the Kosovo Specialist Prosecution in The Hague has been pressing ahead with work on charges against former Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, guerrillas suspected of wartime and post-war crimes.

The new court is due to renew its initial five-year mandate at the end of May. Based on a law adopted by the Kosovo Assembly in 2015, its mandate will continue until Kosovo is notified by the Council of the European Union that investigations have concluded and proceedings are complete – until then, no specific actions need to be taken for the mandate to be renewed.

At the end of April, prosecutors sent more indictments of unnamed suspects to a pre-trial judge, who now has six months to review the charges. A first tranche of indictments was sent to a judge in February and these are expected to be confirmed by mid-summer, before expected trials at the Kosovo Specialist Chambers.

The prospective defendants have not yet been publicly named, but more than 150 former KLA members have now been summoned for questioning as suspects or witnesses, and it is believed that the first public announcements are not long away.

Among those called in for interviews were prominent political figures like Ramush Haradinaj, head of the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo, AAK, who resigned as prime minister when he was summoned, and the former speaker of the Kosovo Assembly, Kadri Veseli, who is head of the Democratic Party of Kosovo, PDK.

The so-called ‘special court’ has never been popular because it is seen as an attack on the KLA’s righteous struggle, and frustration has continued to grow with what is seen as a biased institution that will only try ethnic Albanians while leaving many wartime crimes by Serbs unprosecuted.

For Bekim Gashi, whose mother and four sisters were killed by Serbian forces in a massacre in their village of Terne on March 25, 1999, and whose remains are still missing, the special court is “unfair and farcical”.

“It would be better for this court to treat crimes against humanity equally,” Gashi told BIRN.

“Justice cannot be selective like this court’s mandate is,” he said.

Gashi has had some success in getting justice for his murdered relatives. In 2008, he filed a criminal complaint to Serbia’s War Crimes Prosecution against the Yugoslav Army’s 549th Brigade. In 2019, the Higher Court in Belgrade sentenced former Yugoslav Army officer Rajko Kozlina to 15 years in prison for the murder of 27 civilians in Terne in 1999, while acquitting his superior, Pavle Gavrilovic.

But many other crimes committed by Serbian troops, police officers and paramilitaries during the Kosovo war have never resulted in indictments.

Gashi said that “it is undeniable that some KLA members were involved in crimes against minorities after the war, sometimes to take revenge and in other cases to take their properties”.

But he argued that prosecutions should not just target wrongdoers from one ethnic group: “All crimes committed against civilians should be punished, whatever their ethnic background,” he said.

‘Many view the court’s mandate as unfair’

When the Kosovo Assembly voted in 2015 to establish the Specialist Chambers as a ‘hybrid court’ – part of Kosovo’s justice system but based in the Netherlands – the Prishtina authorities explained it as a way to clean up Kosovo’s image.

Its establishment came in response to serious allegations raised by a Council of Europe report in 2010 written by Swiss senator Dick Marty about crimes allegedly committed by KLA members.

Between 2012 and 2014, a European Union task force looked into Marty’s allegations and concluded there was enough evidence for prosecutions for offences like murders, abductions, illegal detentions and sexual violence.

Kosovo’s political leaders agreed to establish the court under huge pressure from the country’s Western backers, but then in December 2017, President Hashim Thaci supported an initiative by more than 40 MPs to abolish it.

It was unclear why Thaci, one of the KLA’s former leaders, changed his position after initially backing the court as a means of proving to the world that the KLA’s armed struggle was ‘clean’. However, there have been repeated suggestions that Thaci, who was named in the Marty report, could face charges, although he denies any wrongdoing.

Meanwhile many people in Kosovo have grown increasingly dismissive about the court, particularly as five years have passed without any indictments being made public.

Public uncertainty about the court has been further fuelled by recent unsubstantiated rumours that it might be abolished and wartime crimes amnestied as part of a deal to normalise relations between Kosovo and Serbia.

Kushtrim Koliqi, the head of Prishtina-based NGO called Integra, whose work focuses on peace, dealing with the past and human rights, said that misinformation and scepticism about the Specialist Chambers is widespread in Kosovo.

“Based on our public perception research, Albanians overwhelmingly view the court’s mandate to prosecute war crimes mainly associated with the KLA as unfair, while many Serbs believe it is very unlikely that the court can bring justice,” Koliqi told BIRN.

“Kosovo citizens are not against the truth about what happened [during and after the war]. But Kosovo still lacks political leaders who are ready to deal seriously with the legacy of the war and the victims, and not promote war criminals,” he added.

Kosovo Serbs meanwhile are sceptical that the Specialist Chambers can deliver justice in cases in which the victims were mainly Serbs.

A report by Amnesty International in 2009 estimated that some 800 murders were committed during a prolonged outbreak of violence against Serbs and other ethnic minorities in the period when Kosovo was under UN administration after the war ended and Serbian forces withdrew.

The majority of people who were allegedly kidnapped by KLA members and then disappeared during the wider period from 1998 to 2000 were either Serbs or Kosovo Albanians labelled as collaborators with Serbia.

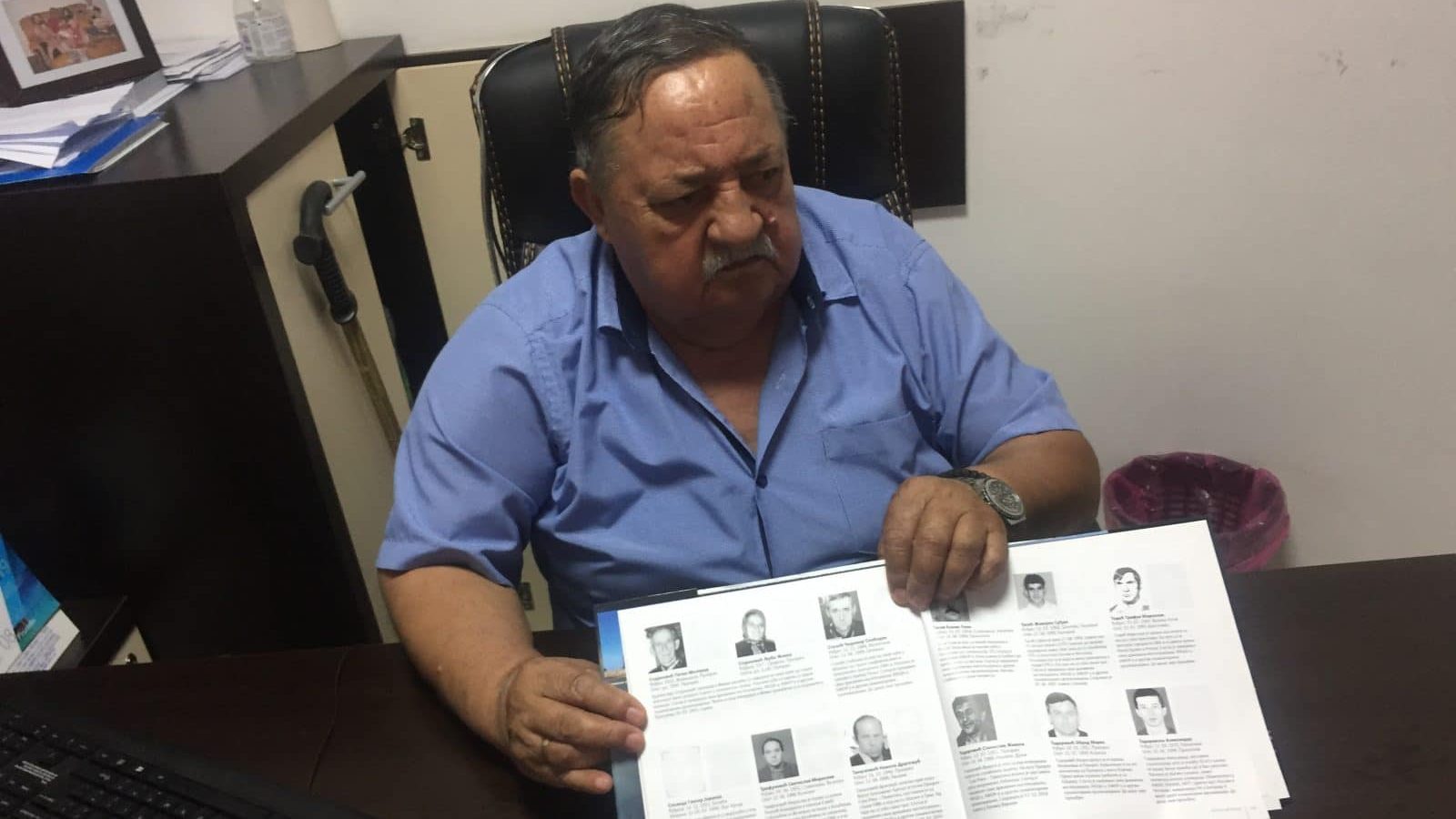

Milorad Todorovic, the co-chair of the Missing Persons Resource Centre, whose brother was kidnapped with four other Serbs during the war and is still missing, said that the court has been losing its credibility because of long delays to indictments.

“Witnesses are passing away but war crimes do not have an expiry date. Sooner or later, we have to face the truth. There are victims on both sides as well as people who committed those crimes,” said Todorovic.

‘Promoting a culture of impunity’

Acting Prime Minister Albin Kurti, whose party Vetevendosje has long been outspoken in its criticism of the Specialist Chambers, recently fired his adviser Shkelzen Gashi for saying that individual KLA fighters committed crimes during the 1998-99 war – comments that sparked a furious backlash from Kosovo Albanians.

Gazmend Bytyqi, an MP from the opposition Democratic Party of Kosovo, said that Gashi’s statements were an “attempt to denigrate the glorious fight for freedom”.

For some however, the sacking showed that Kosovo’s political leadership wants to perpetuate a culture of impunity.

“Political leaders should refrain from such a narrative… Justice must be served for all victims,” said Abit Hoxha, a transitional justice researcher.

The potential undermining of any positive impact the court might have on Kosovo society has led to the Specialist Chambers making outreach a priority.

“From the outset outreach has been our focus,” Michael Doyle, the Specialist Chambers’ outreach coordinator and spokesperson, told BIRN. “The Outreach team travels to Kosovo about once a month to inform people about the court and its activities, to clarify misconceptions and to respond to the questions and concerns that people have.”

But Hoxha said that there are few expectations that the Specialist Chambers will gain widespread acceptance in Kosovo society at any stage.

“When it comes to crimes, we should not look for popular opinion, but justice,” he said.