A walk around the main museums of Prishtina leaves one wondering why these buildings have so few visitors. The author suggests some tips for improving future visitor experiences.

Prishtina’s museums seem empty. Last week, I visited three museums: the National Museum of Kosovo, the Ethnological Museum, and the House of Independence. I never saw another visitor.

This made me wonder: Why are so few people visiting the museums? What can those museums change to attract more visitors?

The emptiness may be partially explained by the fact that March is not the high season for tourists in Kosovo. Covid-19 had a strong impact on decreasing the number of visitors as well, but the numbers seem to be recovering slowly.

However, the museums could also improve the representation of their works and artefacts to encourage more people to visit. Museums should also make more information available online, including their opening hours and new exhibits.

All of Kosovo’s national museums are free to visit and are located within a fifteen-minute walk from the city centre. A few notable improvements would make these museums more accessible, understandable, and exciting for tourists and locals alike.

The National Museum of Kosovo. Photo: Kylie Henry.

‘National Museum of Kosovo’

Hours: Tuesday to Sunday, 10:00 - 17:00

Address: Str. Ibrahim Lutfiu, nr.4, Prishtina

The National Museum has two exhibition floors. One is devoted to Illyrian, Dardanian, and Roman artefacts. The second highlights the Kosovo War, the NATO intervention, and Kosovo’s independence. On the ground floor an information desk is open on the weekends and staffed with a guide who speaks Albanian and English.

On the first floor of the National Museum, case after case is filled with artefacts from 1200 BC to 1300 AD. Displays are full of coins, jewellery, and pottery. Descriptions posted inside the cases detail the names of the items and where they were discovered in Albanian, Serbian, and English.

However, the pieces are not accompanied by further explanations of what life was like during any of these time periods. There is no written information to highlight the importance of these pieces or the societies who created them.

Without these details, the objects are not especially intriguing.

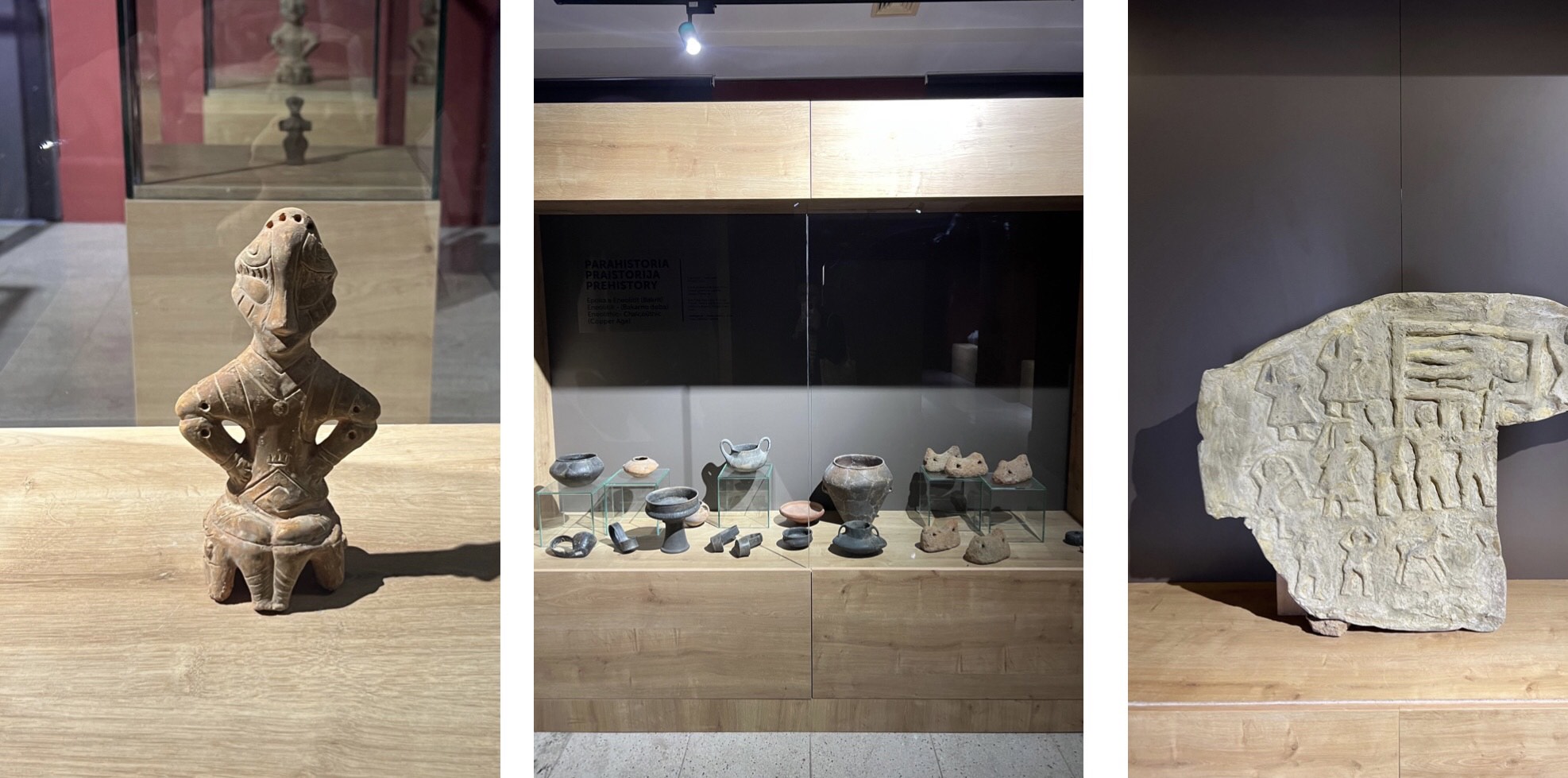

From left to right, (1) Goddess on the Throne, (2) artefacts from the Copper Age, (3) Dardian antiquity showing a funeral procession. Photos: Kylie Henry.

The best example of this information gap is the Goddess on the Throne, a 6000-year-old terracotta piece found in Prishtina, depicting a female goddess from the Vinca culture – a Neolithic society that existed in Southeastern Europe.

She has been adopted as the symbol of Prishtina and of the National Museum and yet there is no information about her available to visitors. Not a single sign indicates the Goddess on the Throne’s historical importance, why the Vinca society produced these figurines or her current role as the symbol of Prishtina.

Moving upstairs, the second floor focuses on Kosovo’s recent history. The walls are lined with collections of guns, uniforms, and rocket launchers from UCK and NATO soldiers. All of the labels are written only in Albanian.

There are no details about the number of people who were killed or forced from their homes. No photos showing the destruction and devastation of the war. There’s no information about why the war started or when; no personal stories from war heroes, refugees, or survivors and nothing to educate visitors about the genocide. There are no artefacts from civilians who survived the war, only pieces of military equipment.

Display case at the Kosovo Museum. Photo: Kylie Henry.

Even the military pieces displayed in the museum lack proper signage. In the display case shown above, only the names of the owners of the clothing are displayed: William Walker’s jacket, the uniform of Wesley Clark, the uniform of Faruza Kallaba, and a uniform of an “Atlantiku” officer.

Who are these people? While they might be well-known figures in Kosovo, they deserve an explanation: so tourists and future generations can understand their important roles in the Kosovo War.

William Walker was the head of the OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission from October 1998 to June 1999. He visited the site of the Racak massacre and called it a “crime very much against humanity.” Wesley Clark was the Supreme Allied Commander of Europe (NATO) from 1997 - 2000. Faruza Kallaba was a female Albanian-American pilot who flew missions during the war.

The museum does a disservice to visitors by focusing only on the military aspect of the war. The human stories are lost. A more comprehensive exhibit would give visitors an understanding of the oppression, destruction, and rebuilding that has taken place in Kosovo – and how the lives of ordinary civilians were affected.

By only presenting ancient artefacts and the very recent history of the country, the National Museum also leaves more than 800 years of Kosovo’s history unexplained. Visitors are left to wonder about the people and events that took place.

The museum does not display any pieces from the Ottoman Empire or the Albanian national movement of the 1870s. There are no artefacts or information about life in Kosovo during World War I or World War II, or when Kosovo was an autonomous province under the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia.

Although it is a young country, Kosovo has a long, complicated history that is worth telling. Focusing only on ancient history and the Kosovo War does not give visitors a full picture of Kosovo’s past.

In addition, nowhere in the museum are visitors informed that some 1,200 stolen artefacts from the National Museum are in Serbia. The pieces were taken to Belgrade during the war in 1998 and never returned. Visitors should be informed of this injustice.

At the very least, the national museum should include more descriptions of the pieces shown to help visitors understand what they are looking at.

The museum could also enhance the visitor experience by offering an audio guide that can be downloaded onto a phone and listened to throughout the museum. The voice of a local guide could explain the history of the objects in the museum in Albanian and English. Upstairs, the audio guide could include audio clips from war heroes and survivors to bring the stories of the war to life.

The museum could also benefit from an official website. For now, their Facebook page serves as their platform for public communication and updates about exhibits. However, the current Facebook page does not show the museum’s hours or official address, leaving potential visitors unsure when and where they can visit.

Furthermore, the Kosovo Museum is not accessible to wheelchair users or people with other physical limitations. The displays are located on the first and second floors and are accessed by climbing stairs. Although the National Museum has elevators, they are currently out-of-order.

When visitors come to the National Museum, they should leave with a better understanding of the history of Kosovo. In order to improve visitor experience, the Kosovo Museum needs to provide more written or audio information about the pieces displayed, life in Kosovo between 1300 and 1998, and the civilian experience during the war and post-war years.

‘Ethnographic Museum of Kosovo’

Entrance to the Ethnographic Museum. Photo: Kylie Henry.

Hours: Tuesday - Sunday, 10:00 - 17:00

Address: Rr. Iliaz Agushi, Prishtina, Kosovo

Tripadvisor recommends the Ethnographic Museum as the #1 Thing To Do in Prishtina. It has certainly earned its place on this list – entering the museum feels like stepping back 300 years in time.

Volunteer guides provide free tours of the Emin Gjiku complex in English and Albanian. The museum does not have written descriptions of the objects inside, but these are unnecessary because of the guides.

The professional guides are incredibly knowledgeable about the pieces on display and the history of Kosovo. If you are new to Prishtina, they are also happy to recommend additional museums, activities, and restaurants.

Like the National Museum, the Ethnographic Museum could also benefit from a downloadable audio guide to assist visitors when the guides are unavailable or busy with a different tour group.

Ilir Sopjani, a guide and curator at the museum since 2006, said that the Ethnographic Museum was arranged, “to show the public how life was before – instead of just being a temporary or permanent exhibition inside of one of the more modern buildings.”

The house is an original structure from the 18th century, during which Kosovo was under the control of the Ottoman Empire.

The guest room of the Ethnographic Museum. Photo: Kylie Henry.

The Albanian family who resided here were forced to flee in 1958 because of persecution and anti-Albanian policies. The house was then used as a nature museum.

After the war, the building was restored and opened as an ethnographic museum in 2006. Like the National Museum, the Ethnographic Museum is still missing some of its artefacts, which were taken to Belgrade in 1998.

From left to right, (1) ceremonial dress, (2) reconstruction of a traditional kitchen, (3) advanced central heating system. Photos: Kylie Henry.

The unique feature of the Ethnographic Museum is that it is fully immersive. The building, furniture, architecture, and decorations are all part of the exhibit.

Stepping into the family’s home makes it easier to understand what life in Prishtina was like during the 18th century. For example, instead of reading about the advanced central heating system, you can see and understand how the house was kept warm through an internal system. You can also see where the family entertained guests and where they ate their meals.

There is a second building on the premises of the Ethnographic Museum, which was built in the 19th century. It underwent restoration in 2017, and will soon open with exhibits about life during the 19th century. It will display more than 1500 artefacts.

Unfortunately, the structure of these old houses means that entry requires the ability to walk up and down stairs. The museum is not accessible to wheelchair users.

The museum could also benefit from an official website or a more updated Facebook page. Multiple websites show conflicting opening hours for the museum, and no website lists an exact address for the museum, making it difficult for a tourist to find.

‘House of Independence’

Doorway of the House of Independence and bust of Ibrahim Rugova. Photo: Kylie Henry.

Hours: Monday - Saturday, 10:00 - 17:00

Address: Enver Zymberi street, (next to Tiffany restaurant)

Tucked next to Tiffany restaurant is the hidden gem of Prishtina’s museums, the House of Independence. Although Google Maps warns visitors that the museum is permanently closed, it is open for visitors.

The guide does not speak much English but is happy to show visitors around and point out important photos. In contrast to the National Museum, the House of Independence is full of photos and written descriptions in both Albanian and English.

The House of Independence fills in the informational gaps of the National Museum. An exhibit in the first room tracks the development of Kosovo from 300 BC to today.

Display cases in the first room at the House of Independence. Photo: Kylie Henry.

The rest of the museum is devoted to the independence movement, war, and the role of the LDK. It walks visitors through the oppression of Albanians, the independence movement, the peace movement and the war in Kosovo.

One jarring display explains how Albanian soldiers in the Yugoslav army were returned to their families in sealed caskets, reportedly as ‘suicide cases,’ but opening the caskets revealed they had bullets in their backs. Photos and witness testimony such as this make the war more tangible and heartbreaking.

Adjacent rooms also detail the post-war period, including the UNMIK administration, independence, elections, and international involvement.

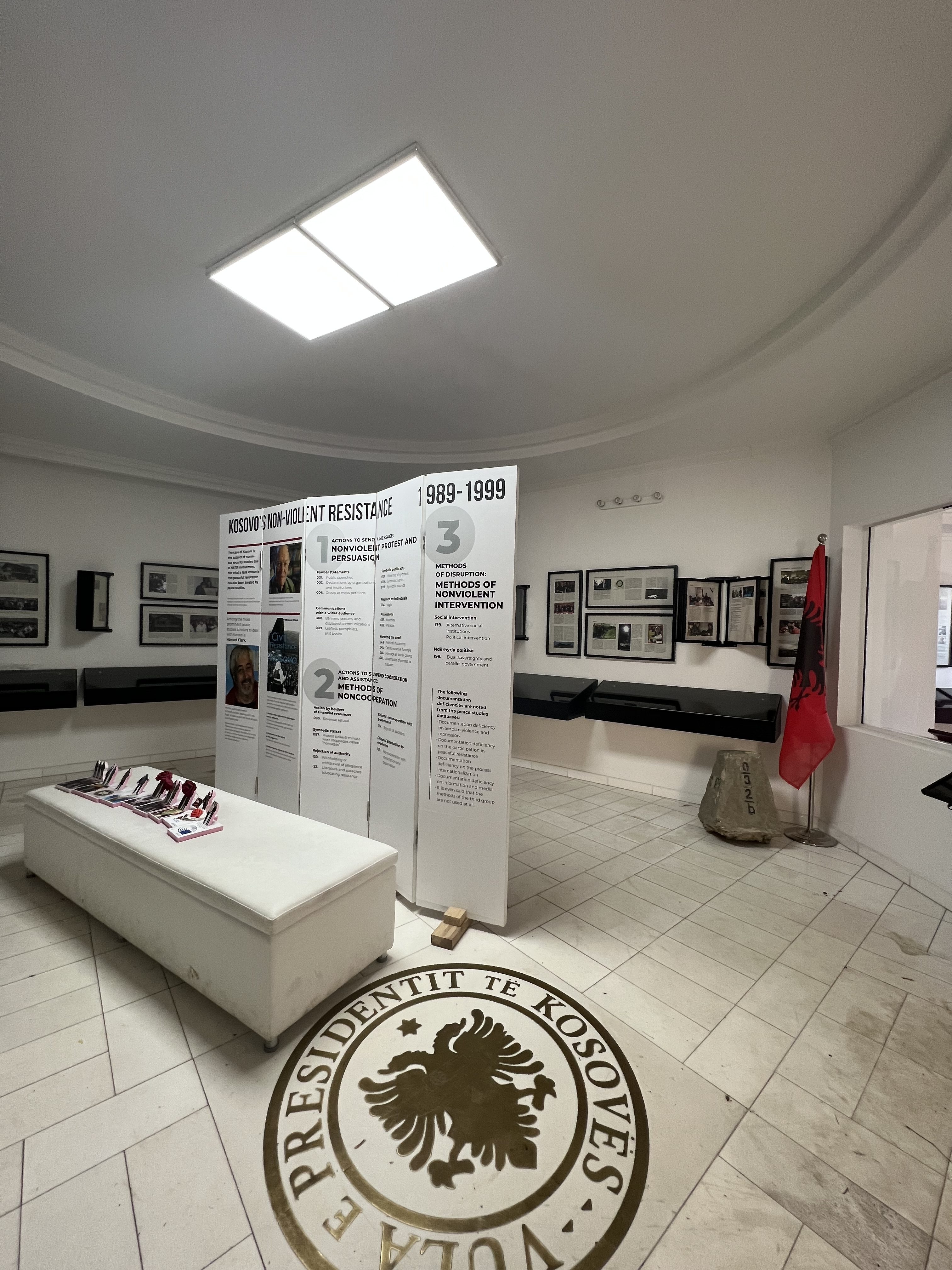

Display at the House of Independence. Photo: Kylie Henry.

The house was home to the Kosovo Writers’ Association and the Democratic League of Kosovo, LDK. Ibrahim Rugova, the former leader of LDK (1989 - 2006) and President of Kosovo (1929 - 2006), had his office inside. Serb forces burned the house in March 1999. Photos of the complete destruction of the house are displayed in the museum.

After the war, the house was rebuilt and reopened as a museum. Rugova dedicated the building to the House of Independence Museum in 2005.

The museum seems to lack many physical artefacts, as the empty display boxes show, but pictures and descriptions convey stories of the war. Some of the empty display boxes found in the museum could be filled with donated items from survivors of the war.

The House of Independence should also publish its hours and address to increase the number of visitors. The first step would be correcting the google maps announcement that says the museum is permanently closed.

The museum is all located on one floor, however, there are three steps leading to the courtyard. Replacing these with a short ramp would make the museum accessible for visitors of all physical abilities.

Overall, for tourists or locals looking to gain a better understanding of the history of Kosovo, the House of Independence provides the most comprehensive and memorable display.

Kylie Henry is a U.S. Fulbright student living in Prishtina, Kosovo. She is currently an intern at Prishtina Insight and an English teacher at the American Advising Center. She graduated from George Washington University with a Bachelor's degree in International Affairs in May 2022.