In an increasingly authoritarian world, Kosovo scored better than most of the region in some aspects of democracy. While PM Kurti takes pride in this, we look at the other side of the coin.

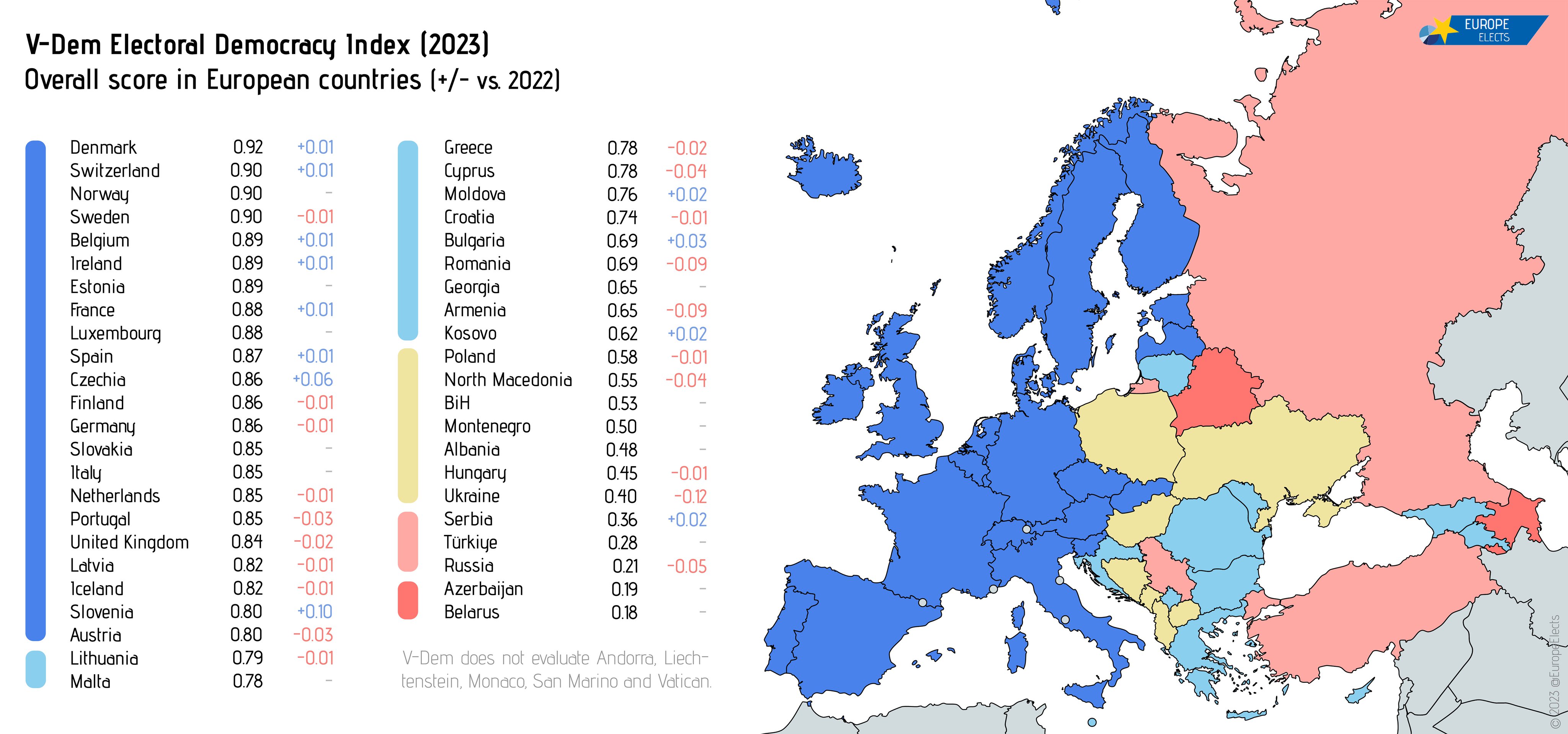

In the latest report of the Varieties of Democracy Index, V-Dem, Kosovo scored comparatively higher than countries of the region in some aspects of democracy.

Photo credits: Europe Elects

Photo credits: Europe Elects

For electoral democracy, one of the five variables of democracy that V-Dem measures, Kosovo compares to Balkan countries that are part of the EU, such as Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania and Greece.

“More validation of our democratic progress,” wrote Prime Minister Albin Kurti on Twitter on Friday, adding that Kosovo had risen three places on the V-Dem list.

“Much work has been done to achieve this result, and there is much more to do. Even better—more democratic—days are still to come”, he added.

Looking closer at the data, however, we see that the results for Kosovo throughout the last few years have been flat.

As seen from the graph, Kosovo has been stable constantly since 2019 and has not managed to pass the result of that year yet.

Leaving electoral democracy aside, and looking at the other four variables of democracy that V-Dem measures, namely, liberal, participatory, egalitarian and deliberate democracy, the results do not change much. In all these categories Kosovo has shown a constant result since 2018/2019, when Kurti’s government was not yet in power.

It appears from the results that Kosovo’s improved ranking is not due to domestic improvement, as scores stayed the same. It was the downscaling of other countries around the globe that led to this increase. Therefore, possibly the biggest merit of the Kurti government has been keeping the situation constant and not downgrading.

An important litmus test for Kurti’s government is the liberal democracy index, which includes protecting individual and minority rights, civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and checks and balances that limit the power of the executive.

Similar to electoral democracy, this variable has not shown any notable improvement since 2019.

During the electoral campaign in 2021, Vetëvendosje’s main discourse was about the war against corruption and organized crime, establishing a bureau for the confiscation of unjustified wealth, and de-politicising the judicial system. In one word, the campaign was built on de-capturing the state.

However, the decisions Vetëvendosje took after coming to power, with regards to state de-capturing, “scared” the EU Commission. In its detailed annual report, which remains the best methodology to keep track of the work of Kosovo’s institutions, the EU Commission was especially worried about the vetting process.

“[T]he potential introduction of a one-off full re-evaluation of all prosecutors and judges is a source of serious concern. Such a process should be considered only as an exceptional measure of last resort,” the EU Commission country report 2021 for Kosovo stated.

The government asked for the advice of the Venice Commission on the process, as the Commission advised, and the report of the following year viewed the vetting process with less concern and on a more positive note.

The EU Commission report advises more work on guaranteeing rights to minorities, gender equality, and the protection of journalists. Threats and physical attacks on journalists flared up recently when covering the situation in the north of Kosovo, for example.

According to the Commission’s report, more needs to be done on women’s political empowerment, where Kosovo has the lowest score in the Western Balkans, and government censorship of the media, on which Kosovo has seen a decrease the last two years.

How is the rest of the region doing?

Slovenian democracy is bouncing back after some years of hardship. Post-communist countries, such as Hungary and Serbia, are now firmly in the territory of electoral autocracies. The rest of the region remained pretty much unchanged.

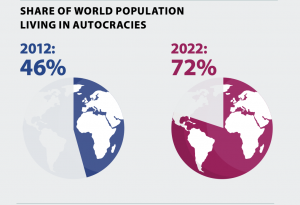

The report, which measures varieties of democracy every year, did not reveal encouraging results for the rest of the world, either. Overall, the number of autocracies has grown significantly compared to ten years ago.

The world has more closed autocracies than liberal democracies – for the first time in more than two decades. The share of the world population living under an autocratic system has increased from 46 per cent to 72 per cent.

Democracy broke down in seven of the top ten autocratizing countries in the last ten years: El Salvador, Hungary, India, Serbia, Thailand, Türkiye, and Tunisia.

Freedom of expression has deteriorated in 35 countries in 2022 - ten years ago, that number was seven, according to the report.

Photo: VDem report.

The V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden uses survey methods to measure and quantify the health of the world’s democracies at a time when authoritarianism is on the rise.

Ardita Zeqiri has contributed to this article.