Renowned Serbian photographer Imre Szabo recorded Kosovo’s gradual descent into turmoil in the 1980s and 1990s, documenting crucial events that led to the outbreak of war and how they affected ethnic Albanians and Serbs.

Left: ‘House for Sale’, Kosovo Polje, May 1981. Right: ‘Shaban and Jordan’, near Kosovo Polje, June 1981. Photos: Imre Szabo.

Talking about how he covered Kosovo, Szabo said he was just “following and noting how events happened”. “I’m a note-taker, I’m not an interpreter. That war, as always, was a mistake for ordinary people. The outcome is that after everything is finished, some people are much richer, while others are much poorer,” he said.

He recalled how he was disappointed when he learned that some people he encountered, both ethnic Albanians and Serbs, had lied to him and his crew about being victims of violence.

But he said that he is still convinced, even now, that reconciliation is possible in Kosovo: “Politicians need to be put in cage to talk and agree. If not, normal people will do it without them.”

A vandalised Serbian cemetery in Kosovo, 1981. Photo: Imre Szabo.

‘You cannot solve a problem with a boot’

Szabo has worked for a variety of Serbian newspapers and magazines including Ilustrovana Politika, weekly news magazine NIN and daily newspaper Danas, but has also taken pictures for many international media such as Stern, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, Newsweek and others.

Born in 1956, he had become an ambitious young photo-reporter by the 1980s – a time he thinks was good for his trade because journalists still benefited from a certain level of trust.

As an example, he cites one of the photos in the exhibition, the one of Slobodan Milosevic giving a speech in Kosovo Polje/Fushe Kosova in April 1987, when he was the head of the central committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country’s ruling party.

“When I got the information in 1987 that Milosevic is coming, I called an editor on the phone and he immediately gave me a car to go there. Those were innocent times. There was faith in young reporters,” he said.

Slobodan Milosevic makes a speech at Kosovo Polje, 1987. Photo: Imre Szabo.

Two years later, Milosevic, who had become president of Serbia by that point, would give another speech at Kosovo Polje/Fushe Kosova to hundreds of thousands of Serbs, during which he established himself as the champion of Serbian nationalism – a speech that some see as the prelude to the subsequent wars and the country’s disintegration in the 1990s.

Asked about his views of Milosevic at the time, Szabo he first thought that he could do some good. But things rapidly changed, as did the photographer’s opinion.

He described the politics of the 1990s war years as “an attempt to solve a problem with a boot. And nothing can be solved with a boot, as we are now well aware.”

Funeral of ethnic Albanian victims of a battle between the Kosovo Liberation Army and Serbian forces, Likoshan, March 1998. Photo: Imre Szabo.

‘Those were dangerous times’

During the 1990s, Szabo covered the conflicts that erupted around the region, but said it was hard to work properly because journalists could not travel anywhere anymore, their movements often limited by their ethnicity. He recalled that he had a gun pointed at his head three times.

“First in Romania when [President Nicolae] Ceausescu was killed, a checkpoint controller pointed at my head,” he said. “The second time, [Croatian Serb rebel leader] Goran Hadzic put a Colt to my head because I photographed some of his people stealing cows and taking them to Serbia.

“And third time was when a soldier smashed his nose doing a [gymnastic] ‘bridge’ movement with his rifle for a photo by the River Zepa [in Bosnia and Herzegovina].”

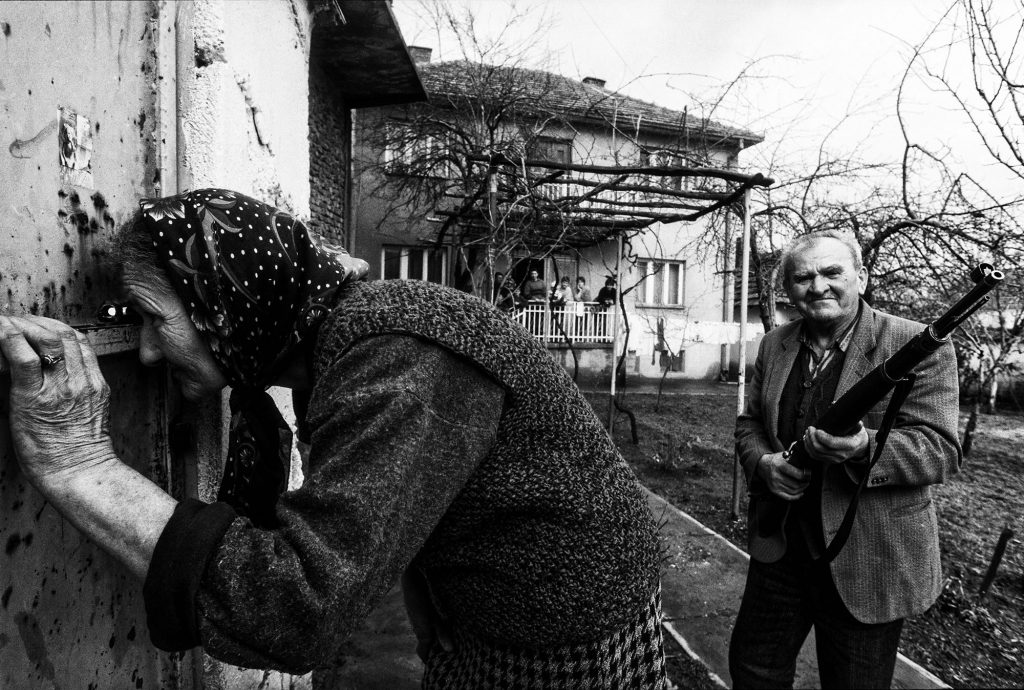

He recalled one of his favourite photographs, entitled ‘Guard in the Yard’, taken in the Djakovica/Gjakova area in February 1999, during the Kosovo war. It depicts an elderly Serb married couple, the husband holding an old rifle while the wife looked through the peephole in the doors of their yard.

“That was the first thing that happened when we visited that family. We entered the yard; about three branches cracked outside and she wanted to check on it. We didn’t stage anything, just reacted instantly to a real situation,” Szabo explained.

“Those were dangerous times. No one trusted anyone.”

‘Guard in the Yard’, near Djakovica/Gjakova, February 1999. Photo: Imre Szabo.

After all the violence in Kosovo and more recent disputes like last year’s row over vehicle licence plates, which again raised tensions to boiling point, Szabo still hopes that relations between ethnic Albanians and Serbs can improve. He said that in his view, the solution has two initials – E and U.

“If we are together in the EU and playing by the same rules, it makes no difference what the licence plates are going to be,” he concluded.

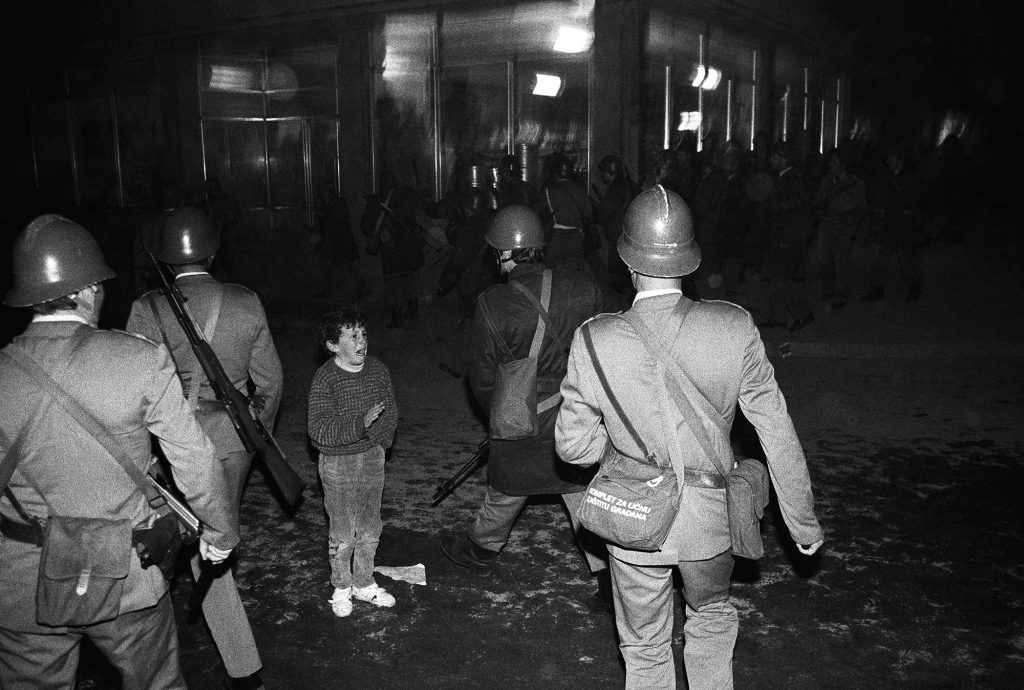

Police in Urosevac/Ferizaj, April 3, 1989. Photo: Imre Szabo.

Kosovo Serb politician Oliver Ivanovic (right) with engineers from the Trepca mine, Mitrovica, August 2000. Ivanovic was assassinated in 2018. Photo: Imre Szabo.

Zoran Andjelkovic, head of the Belgrade-established Temporary Executive Council of Kosovo, watches Serb refugees from Kosovo, June 12, 1999. Photo: Imre Szabo.