A small window takes us back to three years ago. Everyone has a story of experiencing what the world looked like when a virus called COVID-19 had ‘locked us in’.

In retrospect the March 2020 landscape looked different. A virus evoked fear, panic and flight from a new reality that had gripped the world. To keep the enemy outside, all the consequences of the new reality were closed within four walls.

March 13 started the most frightening situation since the last war and emptied the streets. The virus crossed the border, bringing the two first infected persons to Kosovo.

While the situation has calmed down now, there are still cases of infections and deaths. Since the beginning of the pandemic about 3, 250 people have died from COVID-19 in Kosovo.

Looking back at that period, ‘soldiers’ who were the first on the battlefield with COVID-19 told Prishtina Insight about their experiences.

A police officer wears a protective face mask while patrolling on the nearly-empty main square in Prishtina, Kosovo, 27 April 2020. The streets and squares of many cities across the world appear deserted as countries around the world take diverse measures to try to slow down the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that causes the pandemic COVID-19 disease. EPA-EFE/VALDRIN XHEMAJ

Infectious disease specialist’s retrospective

On a morning shift at the Infectious Diseases Clinic at the University Clinical Center in Prishtina, infectious disease specialist Izet Sadiku heard a cacophony of voices, ‘quiet words in the ear’, meetings with the director, anticipation that something will happen during the day. On the same day, the first two positive cases were registered.

An hour later, it was announced that the staff of the Infectious Disease Clinic were suspected of having COVID-19, since the infectious disease specialist who checked the first suspicious case without a full protection suit, was present at the staff meeting.

“We all had contact with the infectious disease specialist, half of our colleagues, the Director of Infectious Disease Department, Naser Ramadani, and [Health] Minister Arben Vitia. I mean, the whole management was suspected to have been infected with COVD-19 on the first day,” he confessed.

Fearing that they could carry the virus to their families that day, everyone stayed in the Infectious Clinic until after midnight, when the results came out.

Clinic for Infectious Diseases in Pristina, Kosovo, 01 September 2021. Photo: EPA-EFE/VALDRIN XHEMAJ

On two fronts, both as an infectious disease specialist and as a future deputy minister who had had contact with COVID-19, Sadiku felt the greatest fear for his family because his little daughter was only 6 months old.

“I told my wife, don’t come home with our daughter, stay at my brother’s house. I called my brother and told him, come and get my son,” Sadiku said.

After three or four days, Sadiku was informed that he would become Deputy Minister of Health. At the same time, he also worked as an infectious disease specialist.

“I feel lucky that I had the opportunity to contribute in both areas. Few doctors in their lifetime have this opportunity – to live by the Hippocratic Oath. For me, it was more dignified that I worked in the clinic continuously because it was the biggest help,” said Sadiku.

A lot of people have compared the pandemic to war. On the other hand, in a war people can desert or flee abroad, in a pandemic there was a ‘war’ in every country.

“There were cases when five patients died in the Intensive Care Unit, which does not happen in normal conditions. To see five people dying within working hours is terrifying,” he added.

During the pandemic, Sadiku said that out of a total of 120 beds about 110 were solely devoted to oxygen therapy.

The greatest horror was the fear that he saw in the eyes of the people.

“At that time, when people were dying in Italy, a 19-year-old student returned to Kosovo from Italy. We tested him once and then he either stayed in the Student Center or isolated at home. He wanted to go home, but his father told him to stay in quarantine. In that moment I saw the instinct of fear,” he confessed.

Sadiku says that during that time there were colleagues who paid for apartments in Prishtina where they chose to live alone, so as not to endanger their families.

“When I came back from work, I went directly to the bathroom to remove my clothes and clean myself,” he said, indicating that he had been isolated in Prishtina.

The Infectious Diseases Clinic bore the greatest burden during the pandemic. Everyday was a tightrope walk between life and death. Critical cases and losses of life were reported at a frequency never seen before in the history of the Clinic.

“There have been cases where the patient’s condition worsened for three hours and in those cases we saw him dying, but there was nothing we could do. You see yourself how small you are in those moments, although we intervened with all the possibilities we had,” Sadiku confessed.

‘In the microbiologist’s laboratory’

A Medical staff wears a protective suit while people wait for the COVID-19 test at the state hospital University Clinical Center in Prishtina, Kosovo, 12 November 2020. Countries around the world are taking increased measures to stem the widespread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus which causes the Covid-19 disease. EPA-EFE/VALDRIN XHEMAJ

At the Institute of Public Health plans were made in advance as the first cases in the region began to be recorded.

The laboratory of the Institute also held a heavy burden. There, samples were analyzed and the results given, which could be the worst news.

Only one news of the day was anticipated – the news at 3 p.m. when the Institute published the daily report of COVID-19.

“The first part was always the hardest. When people received the information that they were positive with COVID, it was like a bomb dropped on them,” said microbiologist Lul Raka, in an interview for Prishtina Insight.

Raka recalled that the beginning was the most difficult period because fear and panic spread faster than the virus itself.

“Sometimes this fear is reasonable because it is about the fear of parents for their children and children for elderly parents. The fear is greater when we are dealing with an unknown enemy,” said Raka.

According to him, the main challenges of the pandemic were diagnostics, how to correctly inform the population, manage the isolation of patients, the logistical aspect of supplying equipment and medicaments, tests, and then vaccines.

“In the beginning, we did not give pessimistic messages so as not to cause panic, even though it is a fact that we have not invested in health for 20 years. Although all governments have said that health is a priority, when the budget cake is divided, health has been given the crumbs. Starting with the laboratory where there is no sufficient investment and no capacity,” he said.

On the other hand, a number of citizens opposed the measures that restricted movement and blamed the compilers of the measures. Cities were closed, schools, cafeterias, restaurants, clubs and everything else where people could meet.

People working in the gastronomy sector attend a protest in front of the government building against restrictions taken due to COVID-19 and the non-provision of economic aid, in Prishtina, Kosovo, 15 December 2021. The Government of the Republic of Kosovo imposed a night curfew from midnight until 5 a.m. and ordered restaurants and bars to close by 11.00 p.m. to stem the spread of Covid-19. EPA-EFE/VALDRIN XHEMAJ

Raka says that the right to life is greater than the right to free movement of people because there are necessary restrictions such as quarantines that are unavoidable.

According to him the most difficult aspect was communicating with the public, since at that time he saw new realities, ‘people with different worldviews, viewpoints, thoughts and goals.’

“Because of the lockdown, there were attacks from some people because the communication environment in Kosovo is bad but I received both threats and praise very quietly,” added Raka.

Even though all possible infected patients would initially contact the Institute’s laboratory, Raka says that at no time did he fear for himself.

“My son is 21-year-old and he has cystic fibrosis, and many families have family members with accompanying diseases. I had the fear for him that there will be consequences: how he is going through it and how he is coping with it ? This was my biggest fear,” he confessed.

‘Inside the patient experience’

Photo: EPA-EFE/VALDRIN XHEMAJ

Faik Ahmeti from Gjilan does not remember four or five days of his life at all.

Having been infected with COVID-19 for more than two months, his condition worsened when he lay in hospital for 11 days.

“I was hospitalized in Gjilan, while my wife was not hospitalized, because there was no place in the hospital. It would have been better if they hadn’t hospitalized me either. I don’t know what happened to me. My daughters and son stayed close to me during the whole time in the hospital,” Ahmeti shared.

Ahmeti blames the doctors because he says that the moment they gave him the oxygen bottle, which according to him was inadequate, his condition worsened more.

“I had so much pain in every part of my body that I felt pain in every cell. I thought that my mind would explode out of my head because of the great pain. I couldn’t bear that pain anymore. After 5-6 days, my family brought me oxygen and I immediately opened my eyes,” he confessed.

When they changed his oxygen tank in the hospital, he says that his condition worsened so much that he was sweating so much that his daughter had to change his clothes three times in a day.

“When I left the hospital, I was devastated, I couldn’t even hold my hand. When I raised my hand, it was like I held 100 kilos on it. I was in that state for two months, then it passed,” Ahmeti said.

He weighed 91 kilograms before COVID-19, when he left the hospital he weighed 79 kilograms.

Ahmeti was mostly challenged by frequent visits to the hospital.

“When the people I love the most come to visit, I was afraid they can’t deal with the pain I was going through,” he said.

Above all, Ahmeti puts the main blame on the health system, which he considers miserable because they did not have proper care, the bathrooms were in an appalling condition, there was no hot water and they were not cleaned with specialist hygiene protocols.

‘In the hands of the pulmonologist’

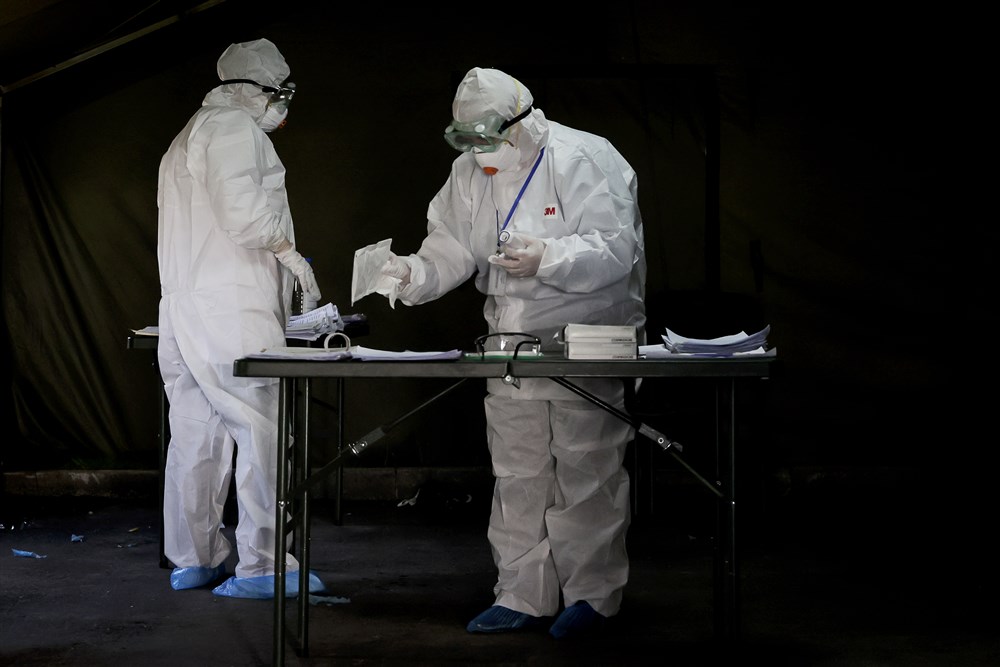

Medical staff wearing protective suits work inside a tent while waiting to assist patients in Pristina, Kosovo, 06 April 2020. The Government of the Republic of Kosovo is enforcing a curfew from 5pm to 6am and has closed borders, schools and public facilities in order to prevent spread of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 which causes the Covid-19 disease. EPA-EFE/VALDRIN XHEMAJ

“Every day there were 2-3 people who died. We had tragic cases where father, mother and son were in the same room. I told them to take the boy away so that he does not see his parents in that condition. But fate has it that the father died, the mother survived and the son survived,” the pulmonologist Skender Baca told us.

Following the Infectious Disease Clinic, the burden was shared with the Pulmonology Clinic – where the consequences of COVID-19 were treated.

Baca considers the greatest horror to be that they did not know who was going to survive, “because we could not predict a prognosis, whether they will survive or not, because there were many factors, including genetic ones.”

For 365 days of the year, Baca rested only one night in Valbona/ Albania because his annual vacations were banned, he also worked after hours in the Clinic and in a private hospital.

“Some of us worked until 11p.m. Because of my age, I couldn’t do it any more, as I got infected four times. But, after a year of being in contact with COVID-19, morning, afternoon and in the second shift, it is impossible not to get infected,” he said, revealing that he felt the greatest fear when the number of staff deaths increased.

More than 3,300 health workers have been infected with COVID-19, of which 1,168 are doctors. 21 doctors have died as a result of infection with COVID-19, according to Institute of Public Health data.

During the pandemic and especially during the quarantine he had no external contact with anyone, even with his daughter.

“All day at work, and in the evening, we only met for five minutes to say goodnight to each other. Contact was zero. At that time we did not think at all that we only slept and worked. Sometimes when I was sleeping I felt every cell of my body ache,” Baca said.

Baca says he has only seen so many deaths when he worked for ‘Doctors without Borders’, and he saw people die in massacres.

“In those families where there is no tragedy, they forget the pandemic. Those who have had someone who died will remember this time badly,” he said.

The 65-year-old will retire in August and after retirement he plans to write a book about the pandemic.

“The whole Covid-19 story is another story,” concluded Baca.