Professor Linda Ziberi reflects on her experience with Finland’s Higher Education system and the potential benefits it could bring if applied in the Western Balkans.

When two of my students, Kanita and Fjolla, returned to Kosovo from their Erasmus+ exchange semester at the Häme University of Applied Sciences, HAMK, in Finland, they spoke of how this experience had fundamentally changed them.

“Finland taught me the beauty of silence, the strength in independence, and how to appreciate the simple things. I worked on projects that mattered, grew in confidence, and discovered parts of myself I didn’t know existed,” Kanita recalled in her LinkedIn post.

Fjolla shared a similar reflection, “classes were hands-on, relaxed, and built around real life, not just theory. We learned by doing, not by memorizing. Outside school, I saw how much people respect quiet, personal space, and trust. Every class, project, and conversation helped me find and know myself better. I came [to Finland] feeling uncertain, and I left feeling more open, confident, and inspired than ever.”

Their reflections reminded me of my own experiences in Finland, where I went twice through Erasmus+: first in May 2023 at Metropolia University in Helsinki, and later in April 2025 at HAMK in Valkeakoski, a town about 150 kilometers distance from Helsinki. After 25 years of teaching experience in the Western Balkans and the US, where I also completed my own graduate studies, I was struck by how profoundly Finnish education thrives on trusting the learner. On both visits, I saw students moving with quiet confidence across campus, free from the performative pressures I have often witnessed in other academic settings.

At HAMK, I taught cross-cultural communication to international business students, advised teams developing community engagement strategies with city officials, and joined an intensive week where international students collaborated with a local energy company.

At Metropolia University in Helsinki, I observed health students manage a simulation hospital and engaged in debates about knowledge sharing, simulation-based learning, and the role of artificial intelligence. What impressed me most was how naturally Finnish students took ownership of their learning, whether managing complex patient care scenarios or guiding a simulated childbirth.

I noticed that the classrooms and university halls in Finland were buzzing with energy, yet the atmosphere was calm. There was no frantic rush before classes, exams, or events, still, everything progressed smoothly. Professors trusted students to take responsibility for their learning and students trusted professors to guide rather than dictate. Institutions trusted faculty to innovate and build community partnerships and faculty trusted institutions to sustain them.

At first, this calm and trusting environment felt unusual. But I soon realized its strength came from how Finnish higher education gives students agency and builds trust into every part of the system.

Navigating different higher education systems

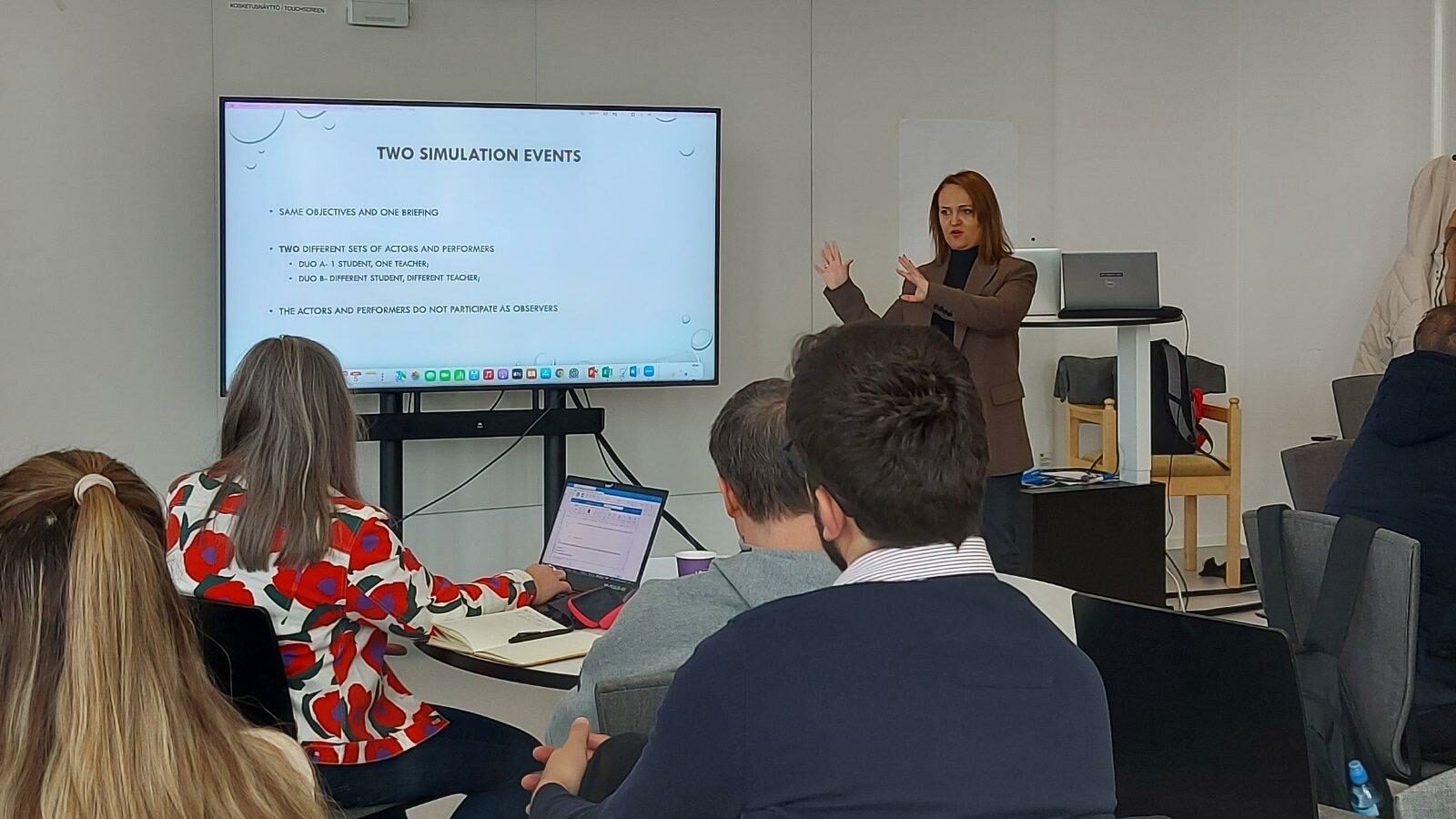

Professor Linda Ziberi at the Metropolia University in Helsinki, Finland. Photo courtesy of Linda Ziberi

In the Western Balkans, students have long navigated education systems that prioritize memorization over original thought. As an undergraduate in Skopje, North Macedonia, in the 1990s, I measured academic success by my ability to memorize and reproduce information. Professors lectured, we copied their words into notebooks, and exams tested our ability to recite them back. With limited access to textbooks or libraries, handwritten notes became our most prized resources, preserved and passed down like treasures. While this system instilled discipline, it left little room for curiosity or creativity.

Everything changed during my graduate studies in the United States in the early 2000s where I was expected to speak in class, write analytically, and solve real-world problems, such as designing PR campaigns, engaging with actual leaders and professionals from the industry in classes, and conducting ethnographic research in virtual spaces. These experiences taught me that learning deepens when students connect theory to practice and are trusted to make meaning themselves.

Still, the American model has its own shortcomings, as it often promotes competition, while Finland emphasizes collaboration grounded in trust. Finnish education expert Pasi Sahlberg describes this as “intelligent accountability with trust-based professionalism.”

During both of my visits to Finland, I saw students work on projects tied directly to community needs, creating services for the elderly, developing strategies for local companies, and mapping cultural landmarks. Professors were not there to lecture, but to guide and support. Students led the way, conducting interviews, doing research, and coming up with solutions that mattered.

While project-based learning is not unique to Finland, the low-pressure environment and the respectful dynamic between professors and students make the difference. I observed faculty treating students as collaborators. They offered direction without taking control and encouraged students to go beyond what was required. A memorable example was Human Resource Management Intensive Week, where students partnered with a local energy company to design ways to attract international talent. As professors stepped back, students managed their own process, researching, debating, and presenting their ideas. There was no control, but still, everything went smoothly.

Importance of creative freedom in the age of AI

Professor Linda Ziberi at the Hämme University of Applied Sciences, HAMK, in Valkeakoski Finland. Photo courtesy of Linda Ziberi

These experiences left me wondering whether the future of higher education in the age of AI will depend on giving students freedom to shape and interpret their own learning. AI can generate answers, but it cannot replicate human judgment, ethical reasoning, or creativity. Reports by the World Economic Forum and Harvard Business School highlight that empathy, communication, ethical reasoning, and creativity remain irreplaceable by automation. Meeting these needs requires trust, purpose, and freedom at the heart of higher education.

As Bell Hooks wrote, teaching is “the practice of freedom.” Now, when AI can generate facts but not human wisdom, Finland’s learner-centered model, rooted in trust rather than control, is not just an ideal, but a critical imperative for the future of higher education. AI can supply answers, but it cannot replicate the kind of understanding that comes from dialogue, reflection, and lived experience. My educational journey and both my visits to Finland lead me to conclude that the survival of higher education will depend on creating environments where learners think deeply, act with integrity, and engage with complex issues.

In the Western Balkans, where education is still defined by exams and hierarchy in many higher education institutions, this shift can start small. Faculty can be trained to take on the role of facilitators rather than authorities, creating more opportunities for discussion and reflection. Students can co-design assignments with faculty, allowing them to shape their own learning outcomes and project goals. Academic programs can incorporate community-based initiatives that turn academic knowledge into tangible and sustainable impact.

These steps may not demand large budgets, but they do require a willingness to trust the learner. It is high time that institutional leaders start recognizing students as capable contributors rather than passive recipients, while treating technology as a partner in thinking, rather than a substitute for it.

As Gert Biesta reminds us, education always involves “the beautiful risk” of allowing the learner to emerge through dialogue and transformation. It is a risk that cannot be measured or controlled, yet it may be what higher education needs most at this time.

Linda Ziberi is the School of Individual Studies, SOIS, Programme Head at RIT Kosovo, where she works to make higher education more inclusive and future oriented. She holds a PhD in Communication and Culture and leads an EU-funded project on mental health and digital transformation.