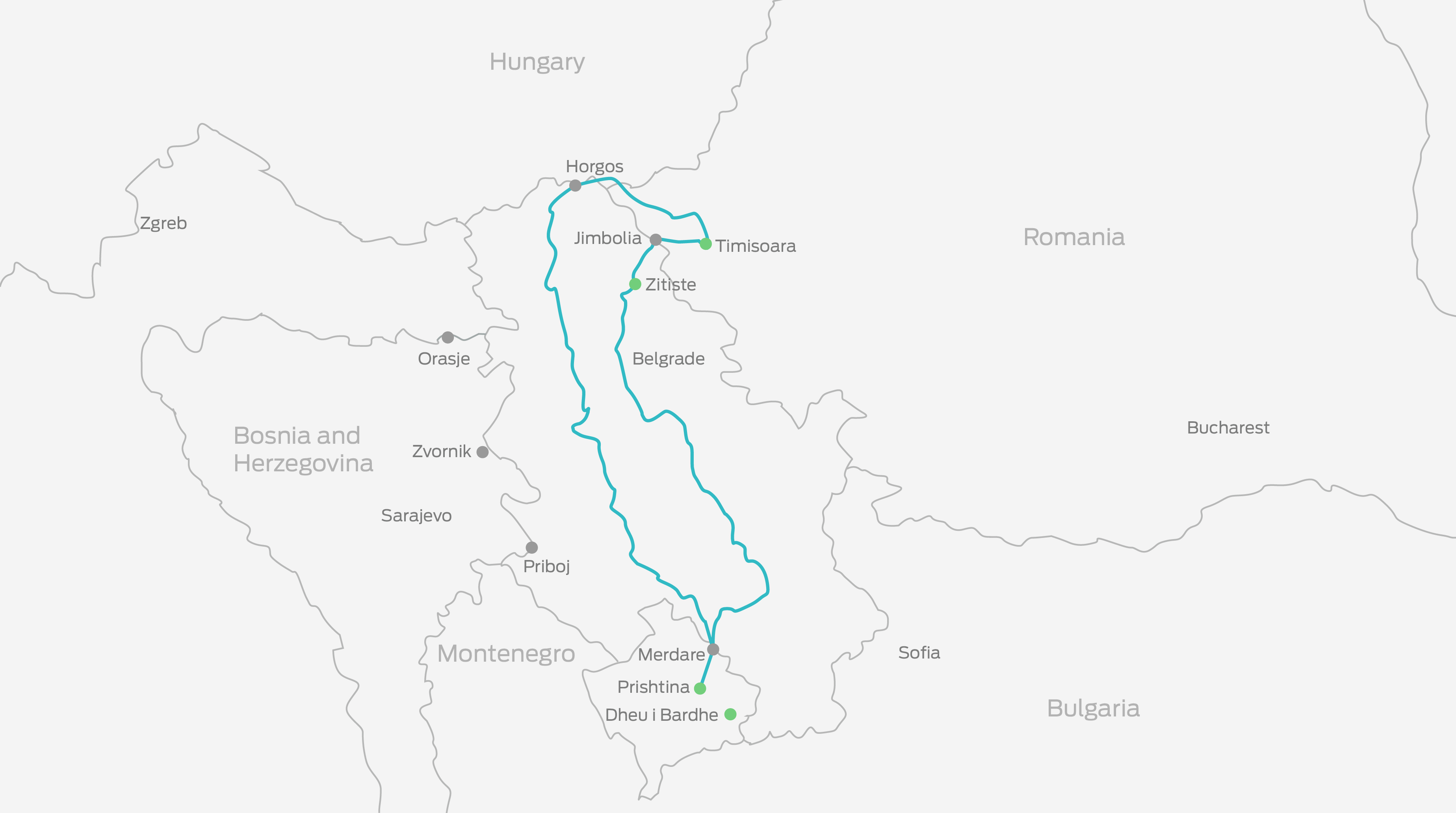

Our correspondent tests the limits of Kosovo-Serbia agreements on a bureaucratic roller-coaster of a trip to Romania through Serbia, trying not to get arrested en route.

PRISHTINA: Introduction

Easter break; school is out. I am up for something experimental, dragging the kids along. Already introduced to the concept of Dracula by Scooby Doo, they go along with the idea of heading for Romania. I collect my partner in Belgrade straight off the plane from a mission in Central Asia. Our trip was partially his idea. A handy second driver and brain, albeit initially jetlagged, attuned to the steppe and watching out for stray camels.

We decided on Romania specifically to test out a simple question I put to Kosovo authorities recently: can we make it across the border between Serbia and Romania with Kosovo license plates?

We get a suspiciously oblique answer – but, because it is a journalist asking the friendly Kosovo official volunteers, we get: “That is such a non-story. Let me give you something else much better.”

Kosovo is a small country: if you want to head practically anywhere in northern, western or eastern Europe, the most direct way to get there is through Serbia. Or at least, it should be. Serbia does not recognize Kosovo yet, but five years ago it signed an agreement on ‘freedom of movement’, in which it agreed terms by which Kosovars are allowed to travel through its territory by using ID cards (never passports) and temporary license plates.

As a Kosovar I can never quite be sure in what genre to approach a trip into Serbia. The world of EU-brokered agreements would suggest we can now relax into gentle comedy, but our decades of trauma at their hands keep horror movies in the mind’s eye.

As a Kosovar I can never quite be sure in what genre to approach a trip into Serbia. The world of EU-brokered agreements would suggest we can now relax into gentle comedy, but our decades of trauma at their hands keep horror movies in the mind’s eye.

A genuine experiment would be to despatch Kosovars with no additional resources (like a full rolodex), to see what happens. But as a manager I owe a duty of care, so I make my own family the guinea-pigs, with additional passports of a strong west European country in back pockets, and cute smiley kids as unwitting human shields.

In a nutshell, the Belgrade-Prishtina agreement involves replacing any Kosovo document with a piece of paper that spiritually and administratively denies the existence of Kosovo as a state. To that end, I will be asked remove my car plates at the border. Instead, I have to buy paper replacements at the border and sellotape them in the car’s front and back windscreen.

When the process of dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo began in 2011 it was about how “these will be only technical agreements” all to do with “making life easier” for the citizens of both countries.

Among the first agreements negotiated by Edita Tahiri, Kosovo government representative, and Borko Stefanovic, then the head of the Serbian delegation, was the “freedom of movement” deal agreed on July 2, 2011.

Although this arrangement has been in place for more than five years now, it has not been easy to decipher exactly what borders Kosovo nationals can cross with their vehicles.

It comes as no surprise to me that Kosovo and Serbia have not fallen over themselves to pass on practical messages to their citizens about the travel arrangements agreed for us in Brussels, but you would assume that by 2016 one or more of the responsible parties – the EU, Kosovo or Serbia – would have posted a website in English, Serbian and Albanian informing people as to what are the exact documents one needs, what is the procedure and which border points Kosovars can and cannot cross.

Witnessing this deficit of information, more than two years ago BIRN decided systematically to monitor the 16 agreements Kosovo has signed with Serbia as part of our “BIG DEAL” initiative.. We teamed up with different NGOs in Belgrade, first CRTA, now BIRN SERBIA and CEAS, and we are putting to the test the degree to which life is ‘easing’ all around us.

Nevertheless, certain things will always slip under the radar if we do not venture out occasionally, with our families, to test them on our own hides.

For example, in 2014 I was turned back from the border and couldn’t cross to Serbia because my children, who are allowed to cross the border with Kosovo birth certificates (since they are younger than 18-years-old they do not have ID documents, but only passports and Serbia does not recognize our passports), did not have a birth certificate issued in the last 6 months.

“Your birth certificate is older than six months and you have not got a stamp that goes over the children’s photo as well as over the certificate” said the Serb border officer at Dheu i Bardhe/Konculj. I went back, enlightened by the new information.

This time round, I make sure to go to the municipality to get freshly printed and recently dated birth certificates and adequate stamping.

MERDARE: Glad Tidings

At Merdare border point, I got my temporary paper plates. | Photo: Alex Anderson.

In the 1990s the Merdare border crossing was a checkpoint which Albanians approached with apprehension. Today it is for Kosovars a border and for Serbs an “administrative boundary line” as, allegedly, you only have borders with countries, but with unrecognized territories you have ‘boundaries.’

It was not an overly frequented crossing for average Kosovan or Serbian citizens until two winters ago – when an estimated 100 thousand Kosovo citizens passed to go to the EU illegally, a journey made possible by well-organized Albanian-Serb gangs of people-smugglers who cooperated with police to make this illegal crossing cheap, knitting together pre-existing travel agency infrastructure in Kosovo and Palic, the sleepy and romantic lake resort in Serbia’s northern province, Vojvodina.

The legacy of this flow of people on the Kosovo side of the border crossing is a clutch of shops and kiosks, now left to make do with the trade from truckers.

A welcome surprise awaits on the Serbian side of the border. Last time I crossed here in 2015, I had to cough up 120 euros to pay for my car insurance, as well as five euros per day of use of the temporary paper license plates.

Insurance companies from both countries imposed extortionate insurance fees on each other’s citizens for four straight years (2011-2015), even though they had signed a deal that was supposed to make people’s lives ‘easier.’ It has taken a long time, and the insurance companies – some of which are very close to those in power – have profited massively in the interim, but finally agreement on mutual recognition of car insurance has been reached, and the fee is abolished.

Now, in spring 2016, all I am asked to pay at the border is five euros for two months’ use of the paper registration plates. I come out of the “Dunav” insurance kiosk at the border quite happy but also baffled. It worked. It was simple. And this was something we got complaints about ever since we started monitoring the agreements. We passed this pressure on to the politicians leading the process. They promised a year ago in our conference that this insurance fee will be removed and finally it has happened. I cannot get used to the fact that citizens’ pressure has actually worked in our post-communist post-conflict countries.

Having passed Merdare, I am now learning to cope with the fact that if something happens and I need my phone, it won’t work. Telecom agreements made between Kosovo and Serbia in 2013, and renegotiated in 2015, still have not been implemented and I have no mobile network with my Kosovo sim card.

I pass signs to the villages of Visoka and Kastrati, but see no roadside habitations. These Albanian names are ghostly reminders of the former population in these virtually deserted tracts. This is all before reaching a turn to go to Kopaonik, which is tempting. I press on to the Nis-Belgrade highway and then towards Romania.

ZITISTE: The missing document

Boxing gloves held aloft, a monument to Rocky Balboa stands prominently in the town square of Zitiste.| Photo license CC.

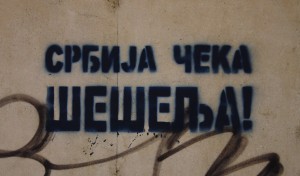

As my mind turned to Dracula’s homeland my eyes alighted on the huge Seselj billboards that appear alongside Serbia’s highways. They pronounce him “Pobednik” (the Victor), rather than than “Innocent,” following the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia’s acquittal of the Serbian Radical Party leader on all nine indictment counts: crimes against humanity, murder and persecution, torture and expulsion.

I like to listen to local radio when I drive through different towns and regions as you get to hear the flavours of the community and it tells you what preoccupies the people inside the buildings of these tranquil-seeming Serbian towns, lovely gardens and house-on the prairie type bungalows.

It is Friday afternoon and on public radio, RTS2, a radio moderator called Biljana is interviewing a veteran Serb general and professor, expert on “hybrid war”.

The decision to acquit Seselj is a harbinger of the West’s belated realisation that it needs Slavic Serbia to fend away the Islamic encroachment, evident with the recent refugee crisis. Soon, he says, our non-Orthodox neighbours: Catholics in Croatia, Muslims in Bosnia and Kosovo, will understand their true spiritual home – that they were all initially Orthodox and must return to these ‘roots’. This is why Russian hybrid war in Ukraine is a just one. And so on and so forth.

An off-message statue we pass in the town of Zitiste, near Romania, jars cutely with his unreconstructed diatribe, which Biljana hosts uncritically. Boxing gloves held aloft, a monument to Rocky Balboa stands prominently in the town square. In 2007 the residents were inspired by the statue of the fictional boxer built in Philadelphia, seeing his life journey with its hard knocks as a reflection of their own. The mayor approved it and a local chicken processing plant paid for the building of the statue.

Shortly afterwards a burly traffic cop pulls me over. I was within the speed limit, so it is the temporary plates that have attracted him. I wind the window down and smile, not realising the genre has suddenly shifted.

“Documents please,” he says.

I give him everything I think he needs to see and I am very much up for a chat. So is he.

“Do you have another driving licence?” he asks.

“No,” still smiling.

“If you have no driving licence I can send you to court, where you will pay a fine of at 100 thousand dinars [800 euros], just like the last Albanian I did, last week – because he didn’t have a driving licence either,” he continues, with scrupulous bonhomie.

“But I have a driving licence!” I say, assured of my position.

“Yes, from a country we do not recognise. So it’s not valid.”

I refer to the agreement and the documents given by the Serbian border police at Merdare.

Tell me where is the document to replace your Kosovo driving licence which we don’t recognise? Policeman in Zitiste

“We give you a piece of paper to replace your ID document that we don’t recognise, we give you a document to accompany the trial plates we give you because we don’t recognise your car plates. But tell me where is the document to replace your Kosovo driving licence which we don’t recognise?”

Usually, it’s not easy to shut me up. I am astounded. I just need to figure out the conundrum of being allowed to cross the border in a car by the same authorities and then being told inland that the rules are different from those at the border. And what is the point of allowing me in, allowing my car in, yet then not allowing me to drive it? Why have our dealmakers failed to sew that one up?

“This means I can send you to court and punish you for driving without a driver’s licence, which is again, about 100,000 dinars.”

That is certainly not my idea of a holiday. But I am also not naïve. I know that being told by a cop twice what the official price of what something costs is inviting a question about what it would take for me NOT to go to court. But I decide I am not in a hurry.

I decide to have a longer chat because nobody in the car is hungry or needs to pee – and they know we are out in an information-gathering project. The kids do not understand Serbian so they think we are having a pleasant chat with the local cop who is only wishing us well for our safety and security.

I decide that there is time to do a bit more haggling. Plus, I am really interested in what happened to this other Albanian last week. I feel embarrassed and amateurish that after two years of monitoring agreements, I have not picked up that you can be heavily fined or banged up for 15 days if you drive in Serbia with a Kosovo driving licence.

This can’t be. I want to believe that this cop is bending the rules as he pleases. But, he is doing this very calmly – he is not in a rush to either let me go, but neither in the rush to arrest me or take me to court. I argue that the border police would not have let me through without a valid licence.

“They are only border cops – they just want you out of their way and policing our law on driving is not their business. It is my job to check whether people have driving licences when they drive in our country.”

I look at the paper they gave me at the border once again. There is one for my ID and one for the trial plates, so he could technically be right. And if he wants to press the issue, he has all the prerogatives. But how come I have driven many times through Serbia and I have never been told this?

I extrapolate from the shame and embarrassment now waiting to spring out of me like a Jack in a Box. Once again, they have found ways to humiliate and beat us up in a dark corner. Same old. And why don’t we get to hear about it? Maybe because its victims are ashamed and embarrassed like me. Nobody’s going to offer sympathy. More like, and what the hell were you even doing there in the first place? What did you expect from them?

“Look, I see you have two small children in the back and it would take you at least a couple of hours in the court so, you never saw me, I never stopped you,” he says.

I am relieved, but foolishly venture some more conversation, referring to myself as a foreigner, tens more questions buzzing in my head. His tone tautens, rehearsing the old Serbian terms of suzerainty over Kosovo’s Albanians – ownership with no rights in exchange. “So, you think you are a foreigner, do you?” I decide to smile, thank him and get out of there.

You Shall Not Pass

Three people share their stories of the bureaucratic hurdles they faced traveling with Kosovar documents, trying to cross at various Serbia-Bosnia borders.

“We who lived only a couple of hundred kilometers away could not make it”

Edona Tolaj

Three other people and I were intending to go to Sarajevo through Serbia. We were attending two regional activities: I was attending the Sarajevo Youth Summit and the other people were attending the Political Youth Network, where members of youth forums of parties from the region participate. Both of these activities are quite important are organized with the aim to encourage regional cooperation amongst youth, with people all over the world and not just the region in attendance.

The process of acquiring the Bosnian visa is a story in itself. Regardless of the fact that we had an invitation from the Bosnian Government, we had to wait almost for an entire month to get an appointment for the visa application. Naturally, we had to apply in Skopje and we did so four of five days before the actual departure date. We actually received our visas a day later than our departure date, so as soon as we got our visas at 3 pm, we left for Sarajevo at 4.

Unfortunately, our journey to Sarajevo ended at the Serbia-Bosnia and Herzegovina border at Mali Zvornik. The reason, we found out, was that according to the agreements reached in Brussels, Kosovo citizens had the right to cross Serbian borders only at certain border points into Serbia and out of it. Serbia-Bosnia border was not one of those, we rudely discovered. We had no information about this beforehand, so we found ourselves in quite a rut. At 3 am we ended up in one of the dodgy motels, where we spent the night before returning to Kosovo the next day.

The irony of this entire story, amongst other things, is that young people from the farthest corners of the world, like Colombia, had managed to get themselves to Sarajevo, while we who lived only a couple of hundred kilometers away could not make it.

“It seemed as if the border police were seeing a Kosovo passport for the first time”

Arben Zharku

About two years ago, I was attending the film festival in Sarajevo where I met two filmmaker friends of mine from Belgrade. In conversation I discovered that they were leaving for the Exit Festival in Novi Sad the next day. Without much ado I decided to go with them to a music festival that I had been meaning to check out for a long time – especially since I had to attend another film festival in Palic (northern Serbia) three days later. At the time, it sounded like a good adventure.

The next day we climbed into an old Renault pick-up truck and began our adventure. It was the first time I was visiting these parts of Bosnia, on the way we passed through different zones inhabited by Serbs and Bosniaks, the traces of the war clear on the ruggedness of people’s faces. Seeing our Belgrade car plates, many children would greet us with Serbian nationalist three finger salute, making me and my two friends uncomfortable.

Once we got to the border separating Bosnia and Herzegovina from Serbia, it seemed as if the border police were seeing a Kosovo passport with a visa printed on a separate paper for the first time. We stopped and waited about half an hour. I am pretty sure that even after they called Sarajevo a couple of times, they got no clear answer. In the end they let us through, bewildered.

When we got to the Serbian side of the border I took out my Republic of Kosovo ID, very happy that our two states had finally reached an agreement for freedom of movement. A Serb police walked over to us and amicably asked for our documents. When he saw my ID, his face changed a couple of shades. Arrogantly, the policeman ordered my friend who was driving to accompany him to the office of the border control. A long time passed before she emerged, ‘tortured’ by the interrogation.

She told me that it was impossible to cross the border, while I insisted that there was an agreement about this and that I wanted to talk with a policeman who spoke English, since I do not know Serbian. They took me to the commander and the atmosphere relaxed a bit when they realized I was an actor and that I do films, and so on.

The police brought a document, a copy of an agreement between the two states, which showed that not all border crossings were included in the agreement – a thing that I never heard about in Kosovo.

The commander was really curious to see how the Kosovo passport looked and I gave it to him. “Wow, it’s very beautiful,” he said, “but why is it also in Serbian?” he asked. Jokingly, using our little friendship I said, “Because there are still some Serbs in Kosovo.” He understood the joke and took it well, and as a friendly gesture explained another way I could get into Serbia. Since I had a Schengen visa, he advised me to cross the other border between Bosnia and Croatia, and then through Croatia cross to Serbia – using a border point included in the agreement.

I thanked him for the recommendation and using our ‘intimacy’ I begged him to make an exception for me and let me pass anyway. He could do that, he told me, but in the end when I’d go to Kosovo through Merdare, the Serbian border police would arrest me for entering the country illegally. There was no other way for me but to go back to Bosnia. Alarmed, I explained to the policeman that I could not go back to Bosnia since my visa for Bosnia was a one-entry visa!

Clearly in good humor he told me, “Don’t worry, just tell the Muslim police that Commander D. told me to do this.”

In the end, it actually worked – I had no trouble going back, with only extra miles added to our Bosnia-Serbia adventure.

“This is not personal, such are the rules”

Erëmirë Krasniqi

For the last five years I did not live in Kosovo. I have been aware of the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue, but the truth of the matter is, I could not keep up with the details. At first it was defined as a ‘technical’ dialogue with the neighbors, then it became a ‘political’ one, although in essence all neighborly relations are necessarily political.

Since I came back to Kosovo, I tend to appreciate all international encounters. They remind me that there is a world out there and it is not defined by daily politics in Kosovo or Serbia. I was invited to participate in a workshop on exhibition Installations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, during which we were supposed to install Damien Hirst’s latest work New Religion. As someone who majored in Art and Aesthetics, I thought the workshop offered a great hands-on experience – I would get to see how the work of a well established artist in the art market is handled by a gallery. I don’t appreciate art that circulates in art auctions or aims at his particular audience, and Hirst’s work is one of them, but I did appreciate the opportunity.

So I started my visa application procedure for Bosnia. I put in quite some effort to gather all the documents needed. As a Kosovar well-versed in the art of visa applications, I was prepared for the occasion. I got the visa, it was handed to me on a piece of paper, not on my passport; validity: six days.

As I google-mapped my way to Bosnia, I realized that the journey via Serbia is the shortest one. I had Montenegro in mind, but that was a five-hour extra drive. I was planning to go by car, hence I could make these decisions more freely. My partner has a car with Croatian plates as well as a Croatian citizenship. For him the decision of going to Bosnia through Serbia was an easy political decision; making this decision felt easy to me as well.

We started the trip in the morning, passed the northern part of the country, Serbian flags waving everywhere. As we entered Serbia, all Serbian flags disappeared. Six hours later we arrived at Priboj, the Serbian-Bosnian border point. I was not permitted to cross the Serbian part of the border with a Kosovo ID. However, the border police-woman was nice enough to explain to me that, “This is not personal, such are the rules.” Since the Kosovo-Serbia agreement does not cover this border point, she suggested I pass through Serbia-Croatia border point at Sid and since I don’t have a Schengen visa, traveling to Bosnia through Croatia was not an option.

As I took a look at this absurd situation, I realized, I was the only thing in the car that could not cross the border: my partner could, the car as well, and all other stuff in our car, but not me.

To make sure, she asked another question, “Do you have any other citizenships?” At that moment, the question felt a bit prejudiced. Since the early ’90s, Kosovars have sought asylum all over Western Europe. Most probably a good percentage of them have double citizenships. I thought, how could it be easier to imagine that I might have another set of travel documents issued by another country, rather than to just let me cross the border between Serbia and Bosnia?

I spent a grim night in Priboj, Serbia, because it was too late to go anywhere at that point. The town was was small and poverty stricken, with decrepit socialist architecture and a river dam. The last cultural event had been a poetry festival, the billboards advertisement announcing the event’s date back in April 2014, a full two years before my trip. The town seemed forgotten, but so did we (by the Kosovo-Serbia agreement).

The next day we drove to Serbia-Montenegro border, which was an hour away from Priboj. I thought maybe they would allow me to go to Montenegro. Maybe, I hoped, their border relations were not formalised yet. However, no luck there. Obviously, I had been relying too much on luck and less on anything rationally established.

I learned the hard way that what the Kosovo-Serbia agreement on freedom of movement of people means is, if you enter Serbia from the north of Kosovo and you are not in possession of Schengen visa, as a Kosovar you are stuck in Serbia. The only way out, is the way in – back to Kosovo.

This might or might not be common knowledge to everyone living in Kosovo, but it wasn’t to me, and there is no official source of information I can find which describes which borders we can and cannot pass.

I was willing to embrace the New Religion, but I was not allowed by the old set of Kosovo- Serbia relations. 🙂

JIMBOLIA: No going back

We reach the border between Serbia and Romania and the border guard, a friendly, good English speaker, assumes cars with trial plates are not allowed to exit Serbia. Clearly until our arrival he has not been overwhelmed by Kosovars eager to conduct experiments upon themselves.

“Let me ask my boss if we can let you out and I’ll come back to you,” he says, going off to phone.

Our reserve passports help the equation here. He explains that they can let us out of the country, but cannot re-admit the Kosovo-registered car through the same border because so far only two border crossings have been designated as entry points for Kosovars into Serbia: Merdare and Horgos (in Hungary).

It is beyond my comprehension why the Kosovo government has failed to make an issue of ensuring that all border points in Serbia, including those with Bosnia & Herzegovina, Croatia, Romania and Bulgaria are passable by Kosovar vehicles. It smacks of the complacency of UNMIK circa 2004 when an acting Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG) commented blithely that the UNMIK travel document issued in lieu of passports allowed travel to most of the places Kosovars would want to go. This kind of ignorant diplomacy bizarrely presumes that, as Kosovars we are unlikely to want to travel to places like Romania, Bosnia or even Croatia – because those border points were not pushed in the agreement for us to cross them.

“I suggest you ask your husband to go and check if the Romanians will let you in, because if we let you go and then they don’t, your car will be stuck in no-man’s land,” said the border guard. Visions of it sitting there, abandoned and rusting away for years while our negotiators slowly get around to negotiating more entry points flickered in my mind.

My partner walked across, getting a confirmation from the Romanian border guards that they will let us and our Kosovo-registered car in and accept my driving licence to boot. He double-checked that the car insurance would not be a problem, explaining that since Kosovo is not a part of the Green Card Insurance system, we do not have insurance for the car for Romania.

The border guards say we can buy it a few kilometres further on and give the OK for us to come over.

However, once we exit Serbia the lack of Romanian car insurance becomes a bit of an issue. First it was fine, but when the Romanian officers call the insurance companies to check they draw a blank. It seems no company will sell insurance for a Kosovo-registered car.

They ask us to go back.

“No way, we told you that we can’t enter Serbia again from here. You assured us we were OK to come in. We specifically asked you about the insurance issue.”

The Romanian officer goes off and we wait.

Eventually her boss comes out and says, “We are letting you go at your own risk because we are nice, we are the EU. We have no facilities to offer car insurance here, but it is also not our responsibility to worry about your insurance – if you are caught driving without it by the police, there is a fine for it”.

If you were nice, Romania would recognise Kosovo, but I keep that thought to myself.

We are letting you go at your own risk because we are nice, we are the EU. Romanian border police

I was of course aware that you need car insurance to drive in Europe but as Kosovo is not allowed to sell this, the way it is usually done seemed always half-illegal to me: what most Kosovars do to get around this is to send a photocopy of their car documents to some kiosk at the border with Bulgaria that issues insurance policies for 90 euros for a month– without seeing the car or the driver – then this insurance is sent back to the driver in Kosovo through a travel agency bus.

But for this experiment I wanted to play it straight.

TIMISOARA: Uncooperative systems

We finally reach the pleasant leafy town of Timisoara, its centre a series of relaxed squares formed by beautiful Habsburg era buildings, where the Romanian revolution that ousted Ceausescu in 1989 first detonated. As Kosovars on holiday we have to devote most of our time to not getting arrested – sightseeing has to take a backseat. We are on a mission to find insurance companies that will insure a Kosovo-registered vehicle, so that we can travel back to Serbia, through Hungary, without fear of being prosecuted for driving without insurance.

As Kosovars on holiday we have to devote most of our time to not getting arrested.

A large newly-built shopping mall has several insurance broker kiosks in a row. Surely one of them will sort us out. One after another tell me that it is impossible to sell a green card insurance to a non-Romanian resident.

I put my foot down and say I am not leaving there until they do some form of insurance. My 3-year old, sleepy, lies down on the insurance kiosk counter. It dawns on the nice woman sitting across the counter that I am seriously not going to leave her office without some form of green card.

She has never been asked to do this before, and neither have any of the other four companies lined up next to her, so they do not know how to go about it. Someone has an idea!

They ring a relative they know in Timisoara who is married to a Kosovar, in the hope he can enlighten them as to what do you do with a Kosovo national who is asking for car insurance. It is a futile endeavour. Doesn’t get us anywhere.

“For my part, I can promise not to claim on the insurance if I have an accident if that helps – all I want is to have the right paperwork if I am stopped by a cop,” I say.

I am asked to sign a paper acknowledging that I accept that my insurance policy is invalid, should they manage to issue me one. The nice woman says she accepts to do this “because of the children”.

This is the third time someone tells me that in this trip. I happily write up the bizarre sentence, which says that I am buying this insurance though I am, at the same time, voluntarily promising that I will not claim it. It is to be purely a cosmetic insurance policy. A souvenir. Date it, put my name in capital letters, signed it. Can I be a tourist now and check out the town?

Not yet.

The computer system is uncooperative. The form into which my details are entered is asking for my Romanian ID number. We try to fool the computer by putting enough digits, zeros, in front and in the back of my Kosovo ID number to create the right 13-digit number, but it won’t buy this brilliant idea of mine.

Unaccepted. Error. Unrecognised.

By this time a little less than two hours have passed.

I am running out of ideas.

But the thought of spending time in jail or court, even if – for variety – Romanian rather than Serbian, stimulates my impulse to come up with something.

I see that the form, apart from registering the car insurance under an individual ID, has an option that allows you to also register the insurance under a business or a company number. I ask the insurance broker to put down their own business number there. This does not go down well.

“We are happy to help you, but not at the cost of risking ourselves,” the nice woman says.

I ring our hotel.

“Excuse me, I am a customer staying with you – can I have the hotel’s business number please?” I ask.

Magically, they give it to me. The system finally accepts it. I am not ‘error’ this time. I manage to register my car insurance under the hotel’s name and business number.

It costs 30 euros, three times less than what Kosovars are paying for the half-legit green card from the kiosks at the Bulgarian border. Although the latter is admittedly a functional policy.

This took me three hours of haggling in the shopping mall – and for all the initial principles of my experiment the upshot was not any more legit than what Kosovars are doing back home with their ways of getting the green card. Probably much less.

My daughter planning our Timisoara visit. | Photo: Alex Anderson.

Now we can visit the Revolution Museum of Timisoara. We had spent so long getting our dummy insurance that it had already closed by the time we arrive. However, they kindly re-open it for us. Time to head back home, looping up through Hungary first.

At Horgos, in the no man’s land between Hungary and Serbia I replace my car’s Kosovo registration plates with the Serbian paper ones, which I have carefully preserved. Upon my approach the Serbian border guard vigorously waves and curses at me from his booth. I drive up in trepidation, fearing he’s blowing a gasket at the impudence of my arrival with Serbian temporary plates I have furnished myself. In fact he was urging me to get a move on.

The entry procedure is done within a couple of minutes and the exit at Merdare is similarly brisk on the way home – a remarkable change from the minimum hour entry always used to take. At Merdare a year ago even our maneuvers to try to cut down the transaction time – switching of drivers as one of us made a beeline for the Dunav insurance office and general buzzing around the car – had so incensed a Serbian border policeman that he threatened to send us back.

I ask the border police both at Horgos and Merdare if my Kosovo driving licence is valid in Serbia. It’s fine, they say.

BACK HOME: A successful Easter hunt

Photo: Alex Anderson.

Not for nothing did we set out from Serbia to Romania on 1 April. It feels like we embarked upon an Easter-egg hunt and wound up as the prey, in a Kafkaesque labyrinth of predators and bureaucracies arranged to entrap, rather than ‘ease’ my ‘freedom of movement’.

My trip was repeatedly reprieved from debacle only by the ‘mercy’ of bureaucrats and officers who were willing to ‘let me go’ and ‘close one eye’ due to the fact that I am a ‘woman traveling with kids’. And, I am not even a refugee from Syria traveling through the Balkans as a strange and unfamiliar territory – but a citizen of this very Eastern Europe where I grew up and where my parents were always free to travel in the ‘70s and the ‘80s before Milosevic came to power.

Kosovar travellers have so many booby traps strewn in our way at ground level that have escaped the eyes of our leaders, focused as they are on ever higher goals, our visa-free travel is not going to guarantee smooth trips either.

In Kosovo, our MFA has spent most of its political capital on highfalutin goals such as getting into UNESCO and we are preoccupied with getting EU visa liberalisation as we are the only Western Balkan country that has not yet got it. Yet I now know that even if we get it, Kosovar travellers have so many booby traps strewn in our way at ground level that have escaped the eyes of our leaders, focused as they are on ever higher goals, our visa-free travel is not going to guarantee smooth trips either.

And maybe the Kosovo official was right when he claimed this is such a non-story. It is easiest for Kosovars to isolate themselves and ‘ease’ their own life by simply not daring to travel anywhere, not risking sudden blows and humiliation. That is a guaranteed way to ensure that nothing can go wrong.

Alex Anderson contributed to this article.

Correction April 24, 2016: A reminder that Kosovo mobile phones still do not work in Serbia, was added to the original story published on April 23.