Anna Di Lellio, an aid worker stationed in northern Albania helping refugees during the Kosovo War, shares the memories of her journey from Kukes to Prizren the day after NATO troops liberated the country.

Prizren, June 13, 1999.

We hear the German NATO tanks rolling out and up the mountains before we see them. The war is over. With my colleagues at the UN World Food Program, WFP, we load a truck with thousands of loaves of bread that Kosovar bakers have been preparing all night.

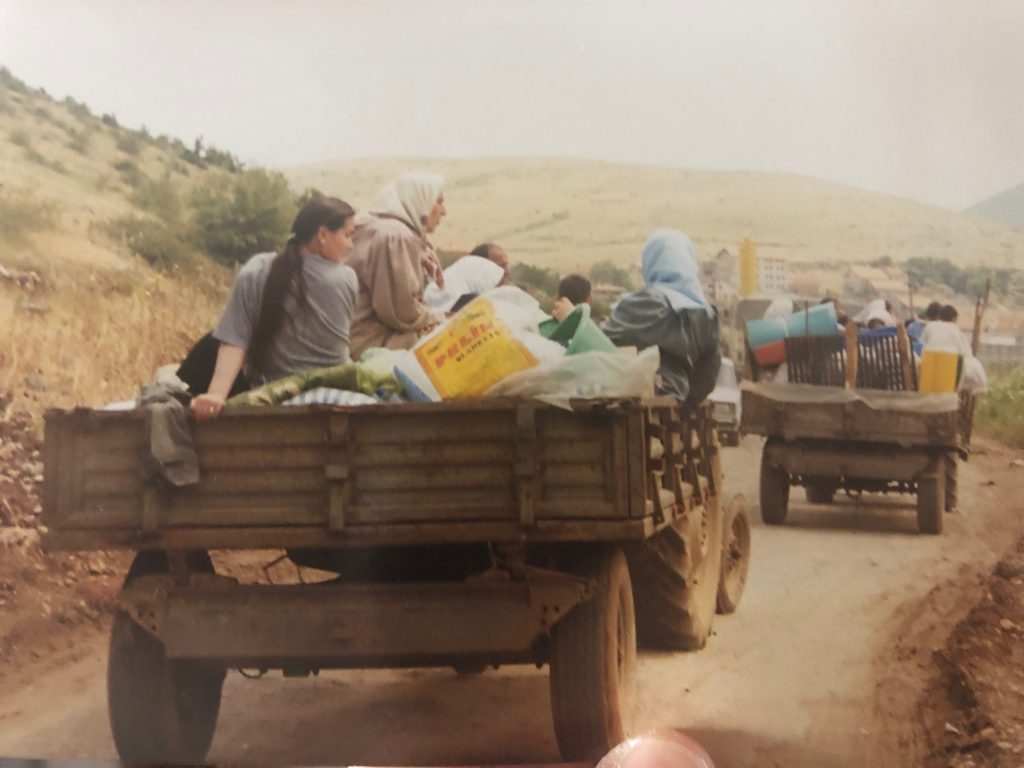

There is no information on the situation that we can trust inside Kosovo. But from the refugees who streamed into Albania in the past weeks, we have seen enough malnutrition to be really worried. Today, we are the only civilians accompanying the NATO troops that are supposed to verify that no Serbian army is left in Kosovo before the refugees can return home.

We spent most of the previous evening on the satellite phone with the UN back in Rome and New York, trying to defy headquarters’ refusal to let us enter Kosovo. The order was to let the troops secure the terrain first. My boss here in Kukes thinks instead that we should go in as soon as possible, because there are rumors of starvation inside Kosovo, and aren’t we ‘the food agency?’

I am the press officer, and my job is to promote WFP to the media from all over the world that came to Kukes to cover the refugee crisis and the war. Instead of a press conference, that same night I organize a dinner. Kukes is a poor town, but one can find pasta, eggplants, tomatoes and white cheese at the market. I have enough to feed about a dozen journalists who have nowhere to go on a rainy night, and are as anxious to get into Kosovo as the refugees. An NGO, War Child, offers their big tent for the party.

By midnight, the negotiation between exhausted UN field workers and the people in New York comes to an end. We won, we’ll be going to into Kosovo. Nobody sleeps, there is too much anticipation in the air.

It is almost lunchtime when we squeeze five people into the white Toyota jeep, all WFP employees except for one Kosovar from Prizren who works with War Child. He volunteered to come with us and be our translator, because he wants to check whether the house he left at gunpoint a month earlier is still standing. His excitement quickly turns into contained panic after we leave the old and ill-kept Albanian roads, lined with refugees who shout “Thank you NATO!” and drive on, past the ghost village of Zhur, to a road lined with Serbian army and police.

Rows of men in different uniforms are lying down, or squatting, on both sides of the road, all staring at the NATO tanks. They are apparently demobilized, so why do they seem so menacing to us?

All of a sudden, a soldier in black jumps to the middle of the road and stops our car and truck. “Who are you and what are you carrying?” The driver, who is a WFP big shot flown in from Tirana that morning to head the mission, calmly answers that we are with the UN and are carrying bread. “Bread for whom?” “For whomever needs it.” Phew! Right answer. We can pass.

Only when the car begins moving again do I notice that our translator, who had dutifully done his job without hesitation, is shaking like a leaf. It suddenly dawns on me that he could have easily been pulled out of the car and killed in front of us.

It would not have been the first time that something like that happened. Wasn’t the deputy prime minister of Bosnia pulled out of a personnel carrier and killed by Serbian soldiers in 1993? The French UN peacekeepers didn’t fire back then, and they didn’t arrest the assassins. What could we, unarmed civilians, have done to stop them here in Prizren?

I don’t know how to comfort our translator, because I cannot even tell him not to worry. “We are with you,” I say, and I feel ashamed and angry. We should have never let him come with us.

The last kilometers of the road to Prizren from the Albanian border are straight and slightly uphill. There is complete silence inside and outside the car. With the exception of the Serbian soldiers, nobody is around. The countryside, punctuated by empty houses, is also empty. Late afternoon, we reach the city entrance sign. Still, not a soul in the street.

Then, all of a sudden, at a small turn that becomes a wider roundabout, we hear the cheers, then we see the crowd. I am reminded of all the films I have seen about the liberation from the Nazis, except this time around, it’s German tanks with the Iron Cross that are doing the liberating.

The Albanians that surround us shout, “Thank you NATO!” We say, “We are the UN!” “Yes, thank you NATO!” This is the first signal I get that the UN does not hold much currency here. Not after Srebrenica.

Compared to us, strengthened and tanned by a month of outdoor living in the mountains of Kukes, the people of Prizren look thin and very pale. I later learn that they have spent the last few months hiding at home, mostly in basements, in fear for their lives.

All the women flock to me. They smile broadly and give flowers to the German soldiers and my colleagues, but they want to touch and hug only me, the only woman in the convoy. One woman gives me an embroidered handkerchief, which could have been one made by my mother back in Italy. I feel overwhelmed. It’s not time to cry though, because happiness is everywhere.

As we park on a side street, planning our next move, other women come out of their houses and offer me rose tea. I have never had it before, but it tastes like the real thing, and I can see roses everywhere, in all the gardens across the town. They ask me where I will spend the night, and offer me a bed in their home. It feels very strange to be at the center of so much care. Shouldn’t I, the humanitarian, take care of them instead?

Behind the main street, long lines of cars are fully packed with people and belongings. Suitcases and even some small furniture are piled up on the roofs. It takes a few minutes to understand that they are Serbs from Prizren, fleeing from the city now that the Albanians who were expelled by their army are about to return. Forlorn and angry, they begin to move out in their own convoy in the opposite direction from which we arrived, to join the Serbian army and the police out of Kosovo.

As soon as the Serbian convoy turns onto the main street, we hear shouting and loud noises. We rush to see what is happening, fearing that the convoy might be attacked in retaliation. That is not the case. It is the Serbs in the convoy that are cursing and hurling objects at the Albanian bystanders. The people who, until yesterday, had either participated in or remained silent in front of the mass expulsion and killing of their neighbors should show contrition, but they display only anger. It’s really absurd.

When the sun begins to set, they are all gone, and everything is quiet again. I taste the best strawberries in a long time, not the huge ones that are hollow and white inside that I find in New York all year around, but the small, red and sweet ones that remind me of my childhood. Come mid-May, my mother would return from the market with the first strawberries of the season and tell us we should make a wish as we ate them, a wish which would be granted for sure.

I had never been to Kosovo before, but here in Prizren so many things remind me of my hometown L’Aquila: the cobbled streets, the red roofs, the mountains in the background no matter where you are in the city, the peasants selling fruits and vegetables, the stubble on the face of the old lady from the village, pricking my skin when she kisses me.

There is nothing more we can do today. They say the first days of peace are the most dangerous and there are still soldiers around. We hear rumors of some killings still happening outside Prizren. I am tired because of the sun, the trip, and the emotions of the day and would be happy to go to sleep, but I have no bed. Instead, I have a spot in the truck’s cabin. For security reasons, the UN says, I cannot accept the many invitations of the friendly locals who have opened their homes to me.

As I fall asleep, I think about the many vaccinations against a host of diseases that I received in Rome before coming to Kukes. I had felt adventurous, like John Reed, who came to the Balkans in 1915 to cover the Balkan wars with his pockets full of mothballs against typhus. Now I feel stupid, and look forward to more of that rose tea in the morning.