For the 10-year anniversary of Kosovo independence, Prishtina Insight met with Shyqri Nimani, the engrosser whose handwriting declared Kosovo as a sovereign state.

For ten years in a row, Shyqri Nimani has been telling the story about calligraphing the document of Kosovo’s declaration of independence. Each year, as the anniversary date nears, he is swarmed by droves of journalists who flock to him with interview requests. And this year, for the tenth anniversary, they seem especially relentless. Yet Nimani said that he turned most of them away.

“There is nothing else to say about it,” said Nimani, who doesn’t shy away from making it clear that he is sick of talking over and over about the same thing.

He has already told the story countless times. How on the eve of Kosovo’s independence, the stakes were high, and how there was a sense of half-secrecy and impending urgency. How if only he were given more time, he would have loved to decorate the margins of the document in golden floral patterns. How he found typos on the printed document they gave him, and how he had to correct them on the go. How as soon as he set up his tools and began working in one of the offices in the government building, they moved him to a different, bigger room, to make him “more comfortable.”

Nimani does not want to talk about the number of times that the Prime Minister or other officials barged into the room to check on his progress with the document that would give rise to the newest country in Europe. And neither is he interested in retelling how it was to work for sixteen hours non-stop until the job was done, refusing any food or drink that was offered him.

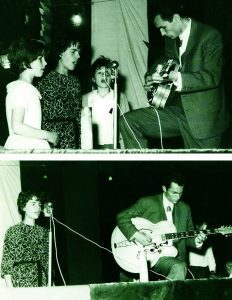

Photo courtesy of Shyqri Nimani.

“You can read about it in my book. Everything is in there,” said Nimani.

And so, instead of talking about calligraphy, we talked about Nimani’s life.

A traveling life

The title of Nimani’s autobiographical artbook — “Neper Gjemba Drejt Yjeve,” from the latin Ad Astra Per Aspera, meaning through hardships to the stars — not only captures the essence of his life’s journey as an individual and an artist, but also mirrors that of Kosovo.

In his childhood Nimani moved around a lot with his family. Although they were originally from Gjakova, he was born in Shkoder, Albania. This was during World War II, when there were no borders between Albania and Kosovo. Throughout his childhood he moved around to places like Kukes, Prizren, Prishtina, and Peja, until he went for his studies in Belgrade.

In a sense, his childhood displacements and wanders might have been heralds to his travelling life. As he says, it is all in the book.

His father died when he was just five. He stayed with his paternal family in Kosovo (then part of Yugoslavia) while his mother remarried in Albania. But soon thereafter the border between the two countries closed and he did not see her again for another 24 years. The episode mirrors the wider trauma many families went through by being separated by two sides of the border, some even without seeing each other for 50 years.

“Destiny wanted that I travel since my childhood,” said Nimani, “and that I not have a permanent station. It was only in the ‘70s that I [returned] to Prishtina.”

Photo courtesy of Shyqri Nimani

But these 30 or so years of moving around were not the end to his travels; merely a new beginning. Nimani now had a new base camp from where to launch into his art expeditions, from the United States, to the USSR, Mexico, England, France, Italy and many other European countries, and all the way to Japan and other countries in Asia.

“I was always a curious person,” said Nimani, “I always wanted to see things with my own eyes.”

He tells of countless travels to participate in exhibitions, meetings, congresses, and symposia. And at each trip he would collect materials and experiences that he would later incorporate into his works and studies.

Stories of Nimani’s travels are ever pertinent for Kosovo’s youth of our times, who are denied this luxury. Even if they want to travel through thorns and adversity so that one day they may reach the stars, they cannot do so because of many travel restrictions that holders of Kosovo passports face.

But Nimani’s was a different time. One of his notable trips was his two-year stay in Japan during 1976-78 on a scholarship from the Japanese Government. He learnt basic Japanese, traveled within Japan as well as outside and visited places like Singapore, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Peking, and Tai Pei. He began writing haiku poetry, and kept a pictorial diary of his experiences and produced a series of artworks titled “Beautiful Japan and Me” that resulted in an exhibition in Japan.

The exhibited works were painted in a technique inspired by the traditional Japanese ukiyo-e style. They featured themes ranging from pictorial transliterations of haiku poems, to an autobiographical painting representing the author wearing a kimono, standing in front of a background of kanji characters and a setting sun, while a veil made out of Yugoslavia’s flag seems to disintegrate, its stars in a disarray.

But one of his works more relevant to Kosovo of today — which in the weeks leading to the tenth anniversary saw Prishtina as the number one polluted city in the world — is a series of environmental posters featuring factory chimneys and the rising smoke that turns into traditional Japanese dragons. In one of them — titled Quo vadis, Japan? (Where Are you Going Japan?) — the famous Mount Fuji is barely visible from the smoke monsters.

A man of twelve talents

While calligraphing the declaration of independence is a crowning lifetime achievement for any artist, perhaps it should also be seen as a natural progression of Nimani’s artistic oeuvre.

Nimani is considered one of the pioneers in graphic design, both in the former Yugoslavia and in Kosovo. In 1967 he graduated from the Academy of Applicative Arts in Belgrade, where he also completed a Masters degree in design in 1969.

“The masters program [in design] started with me. They admitted only one student, and it was me,” he said.

Later he became the director of Kosovo’s National Art Gallery during the ‘80s, and then dean of University of Prishtina’s Faculty of the Arts in the early ‘90s.

Photo: Atdhe Mulla

But long before all that, even during his studies, he had his fingers in different pies. He is a man of many talents, from graphic design, painting, art history, photography, poetry, literature, art criticism, literary translations, and music.

In fact, Nimani had been split on whether to pursue music or art for his university studies. Even after opting for the applicative arts, he continued to pursue his passion for music throughout his student years.

His single Adriatiku was among the first vinyl records in Albanian produced at Belgrade Radio Television. In Croatia the eponymous song got on a list of Yugoslavia’s top songs, and in 1963 Nimani won the public’s prize with “The Student” during Kosovo’s first music festival, Akordet e Kosoves.

Photo courtesy of Shyqri Nimani.

After Nimani returned from Japan, he produced “Kupa e ndarjes” (The Chalice of Separation). Its melancholy lyrics in Albanian were inspired and influenced by the Japanese music of the time.

“But I gave up music some 20 or so years ago,” said Nimani. “Chalice of Separation” was his last song — a title like the final drink after the last call.

“With age, things started to diminish,” said Nimani. “From the twelve fields, now I practice only two: design and making art history books. I am sensible about it. I can no longer practice all of them.”

The book as a work of art

At a time when the very concept of the book is being challenged by technology, the ever-evolving way we consume information, and uneasy competition from the entertainment industry, Nimani stands to be one of the pioneers of book design in Kosovo.

Even though at university Nimani did his masters in poetry book illustrations, just after his graduation he got a job with Belgrade’s National Theatre, designing posters for the opera, ballet, and plays. One day, while preparing plates for theatre posters, he also got to work on his side project — some cover samples for books of Albanian writers back in Prishtina. A gentleman passing by saw them, liked them, and invited him for a job interview the next day. He was one of the editors at Rad, a publishing house in Belgrade.

Nimani’s project at his new job was to illustrate and design the complete collection of poetry books for the famous Russian poet Yesenin. He used acrylic colors, then just new on the market, to paint around 150 images to accompany the poems.

But Nimani’s relationship with literature was not only visual. For Albanian-language newspapers, magazines and journals, he translated short stories and poems from authors like Borges, O. Henry, Lorca, Tagore, and Maya Angelou. He also wrote poetry, short stories, travelogues, and art criticism, and established a collection of sorts of Albanian cultural materials.

“Whenever I was on official travels,” said Nimani, “or at different conferences and symposia, I would, somehow, often find something about Albanians. I would always copy documents, photograph, and collect materials. Over these 40 or 50 years, I created a personal archive of sorts.”

Even at a library in Japan — this was of course before the internet, when literature searches had to be done physically — he found a copy of The Courier magazine, published by UNESCO, whose entire issue was devoted to Onufri, a sixteenth century painter. This helped Nimani later to write a book on Onufri.

Beside his autobiographical art book, Nimani’s more recent book projects include Arnaud, a book about Albanian artists in the Ottoman Empire, and a monogram about Mehmed Ali Pasha, the Albanian ruler of Egypt. He is currently working on a book with the draft title Albanese, about the contribution of Albanian artists to Renaissance art in Italy and other European countries.

Ad astra

The document of the declaration of Kosovo’s independence is not the only thing that bears Nimani’s style. His marks are all over the Republic of Kosovo, from logos of governmental institutions like the Police, as well as businesses, corporations, and other institutions like the Grand Hotel Prishtina, the National Theatre, and the National Gallery of the Arts. His designs are on postage stamps, presidential award medals, and iconic theatre and film posters.

Nimani is hopeful for the 10-year old Kosovo. For him, to see how much Kosovo has progressed, one only has to look back at how it used to be.

“You always get people,” said Nimani, “writing on Facebook or talking with disdain, ‘look at Kosovo, where it has come to.’ But we were never better than now. Do you realize how much progress Kosovo has seen?”

When Nimani returned to Prishtina, Kosovo had around 600 thousand people. Now it has close to two million. Back then in the early ‘70s, the University of Prishtina had just been opened, and Nimani was part of that first generation of teachers that worked there.

Just like one event does not define a person, the same could be said about a country. Kosovo did not just pop up into existence ten years ago. Nimani was the engrosser that put Kosovo’s declaration of independence into writing; surely it was a historic moment, but his life, as well as Kosovo’s history, is more than the sum of its parts.