For the third consecutive year, high concentrations of manganese have persisted for over a month in Badovc Lake—one of Kosovo’s most important water sources—making the water unsafe to drink. The underlying causes remain unclear and institutional efforts are being redirected towards designing long-term interventions to deal with the issue.

In the village of Hajvali, 10 kilometres distance from Badovc lake, the main source of water for Prishtina and its surrounding villages, local resident Imer Demaj pushes a cart filled with empty canisters toward a nearby road in order to catch the next water delivery from the municipality’s tanker truck.

“It’s a bit far from my home, but the real issue is that we can’t always catch the water truck.”

With the main water source compromised, the municipality’s water supply company “Prishtina” has been dispatching tanker trucks—known locally as “autobots”—to distribute clean water to affected areas. But for many residents, the system is far from reliable.

“Hopefully, the authorities find a solution soon. [The cart] is too heavy and it’s too far to carry it like this,” Demaj said.

He also complained about receiving regular monthly water bills despite the supply disruption: “If we’re not getting drinking water, at least don’t charge us the full amount.”

Parts of Kosovo’s capital Prishtina and its surrounding municipalities have been without safe drinking water since September 1, when the National Institute of Public Health of Kosovo, IKSHPK, declared the water from Badovc Lake unsafe due to dangerously high levels of manganese. Now, institutions are trying to find a long-term solution to a problem that is becoming increasingly frequent.

IKSHPK banned the use of drinking water from Badovc Lake after tests showed unsafe concentrations of manganese—a naturally occurring mineral that can be toxic for general health in high doses.

“Laboratory analyses conducted over the past week have shown manganese concentrations exceeding the permitted limit of 0.05 mg/L, according to Administrative Instruction on the quality of water intended for human consumption,” read the latest announcement from the IKSHPK, released on September 15.

A recurrent phenomenon

Aerial view of Badovc lake. Photo: BIRN

This isn’t an isolated incident. Elevated levels of manganese in drinking water lasting more than a month, have been recorded for the last three years—in October 2023, October 2024, and September 2025—and officials warn it may become an annual occurrence largely driven by climate change.

“Previously, we saw elevated manganese levels for a day or two,” explained Arjeta Mjeku, spokesperson for the water utility company “Prishtina.” “But starting in 2023, the issue has become prolonged and more severe. This year, it began even earlier, [in September] and hasn’t gone away,” she added.

Other residents affected by the water contamination expressed concerns about the lack of information about water distribution. Although the water utility company “Prishtina” regularly publishes delivery schedules online, many citizens claim they are not properly informed.

“Today I found the truck, but there’s no guarantee I’ll find it tomorrow,” says Qamil Gashi, also a resident of Hajvalia. “We have to follow [the truck] wherever it goes.”Manganese is an essential trace mineral found naturally in soil and water. In small amounts, it supports bone formation, metabolism, and brain function. But, in high concentrations, especially when consumed over time, manganese becomes toxic.

In 2023, when manganese levels first exceeded the allowed limit for several weeks, Burbuqe Nushi from the IKSHPK spoke about the health risks posed by consuming high levels of this chemical element on the Kallxo Përnime TV Programme.

“Elevated manganese levels primarily affect the central nervous system. They impact intelligence, memory, and learning abilities. In adults, they reduce concentration. If a person is exposed to increased levels of manganese throughout their life, it can cause developmental problems with cognitive issues,” Nushi stated.

According to public health guidelines, the safe limit in drinking water is 0.05 milligrams per liter (mg/L).

In some Prishtina neighbourhoods, recent tests revealed concentrations ranging from 0.117 to 0.250 mg/L – several times above the acceptable limit.

The mineral cannot be removed by boiling water.

Why only in Badovc?

Ciziten filling cans with clean water from a water tank in Hajvalia. Photo: BIRN

Kosovo is home to several artificial lakes, but only Badovc appears to suffer from this recurring contamination which lasts for several weeks at a time.

Built in 1965, Badovc is a 3.5 kilometres long and 30 metres deep reservoir, located 12 kilometres east of Prishtina. Originally serving 40,000 residents, it now supports the water needs of more than 100,000 people.

Its complete dependence on rainfall makes it highly vulnerable to drought and climate fluctuations. “In 2024 we faced the biggest crisis with water reserves in this lake,” Mjeku noted.

Concerning the elevated concentration of manganese, Mjeku stated that, “climate conditions are playing a key role.” “Hot days followed by cold nights increase manganese concentration in the water. But we’re also investigating other contributing factors,” Mjeku added.

Among those potential contributing factors is nearby mining activity which may be influencing the chemical balance of the surrounding soil and groundwater.

To better understand the source of the problem, the “Prishtina” water supply company has partnered with the Institute of Chemistry at the University of Prishtina to conduct in-depth studies of the lake’s ecosystem and sediment composition.

“We want to understand why this is happening in Badovc and not in other lakes,” says Mjeku. “This will help us find a sustainable way to prevent or manage it.”

She added that this study was not comissioned immediately in 2023, when the problem first arose, because officials belived that, “it wouldn’t happen again,” noting that in previous years elevated levels had only persisted for a day or two at a time.

Aging infrastructure, rising demand

Aerial view of Badovc Lake. Photo: BIRN

The crisis also reveals deeper systemic issues. Kosovo’s water infrastructure, much of it built decades ago, is no longer adequate for the needs of its growing population. Meanwhile, climate change is bringing longer dry seasons and more erratic precipitation, thereby reducing the amount of water that can safely be stored in reservoirs like Badovc.

Badovc Lake is connected by underground pipelines to Lake Ujman, Kosovo’s largest reservoir, located in the northern part of the country, but this lifeline is in need of major repairs.

“This area is experiencing rapid development and demand for water keeps increasing,” reads a recent report from “Prishtina.” The report goes on to advocates for additional investment in the lake’s infrastructure: “It’s urgent that we invest in restoring the Cagllavicë–Badovc pipeline so we can refill the lake from Ujman during periods of drought or future contamination events.”

“If the population and the demand in this area keep growing, then Badovic won’t be sufficient to meet 24-hour demand anymore,” Mjeku added.

The Badovc water crisis is not just about one lake, it warns of broader vulnerabilities in Kosovo’s water management system and reservoirs. Because of climate changes like softer winters and aging infrastructure, the country will need to invest in smarter, more resilient systems of critical infrastructure that can provide for the population’s basic needs.

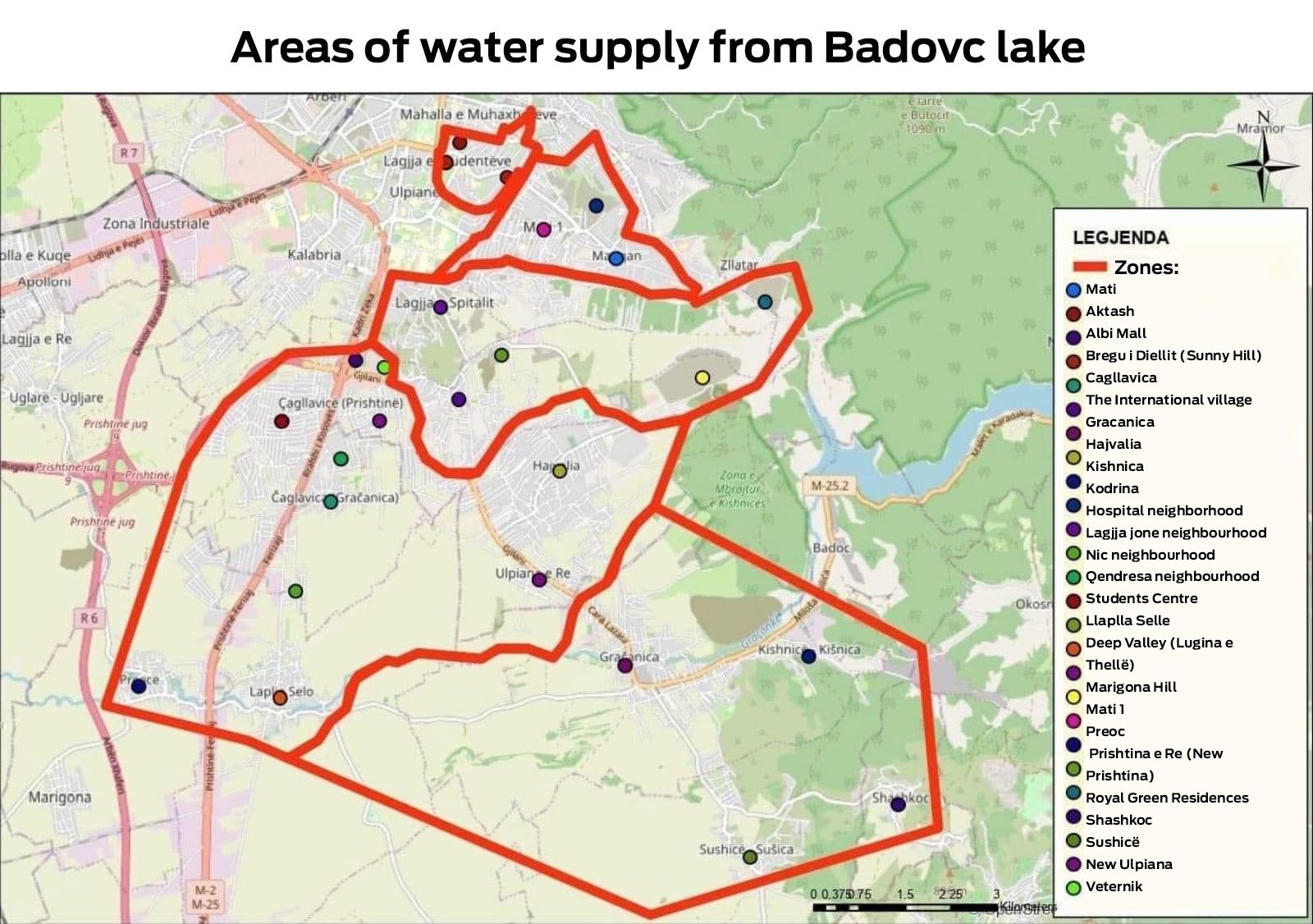

The map of the areas supplied with water by the Badovc lake. Photo: ‘Prishtina’ water supply company.

The Badovc Lake supplies water to several areas and neighbourhoods of Prishtina, such as: Mati, Aktash, Bregu i Diellit (Sunny Hill), Prishtina e Re (New Prishtina), Veternik, Matican, the International Village, the Student Centre, the Industrial Zone, the Hospital Neighbourhood, Kodrina, Marigona Hill, and Royal Green Residences.

This lake also supplies the municipality of Gracanica and the surrounding neighborhoods and areas: Gracanica, Kishnica, the Nic neighbourhood, Lagja Jone (Our neighboUrhood (Lagjia Jonë), Cagllavica, the Qendresa neighborhood, Llapllasella, the Deep Valley (Lugina e Thellë), Preoc, Shashkoc, Sushica, and New Ulpiana.