For the first time in 25 years, Besnik Mehmeti, an ethnic Albanian photographer from North Macedonia, is showing his images documenting Kosovo Albanian refugees and the grim reality of war during NATO’s military intervention in 1999.

“I entered Kosovo immediately in June 1999 along with the NATO troops and saw the destruction of cities, the burnt bodies inside houses in the Pristina region,” Besnik Mehmeti, ethnic Albanian photographer from North Macedonia, told BIRN in an interview.

Mehmeti, a London-based video editor at Al Jazeera – whose photos will be exhibited for the first time at BIRN’s Reporting House in Pristina on June 10 – explained that after the war “everyone had something to say. I wasn’t even ready to talk about these things myself, and I have kept that material wherever I went, having exchanged many homes”.

“I couldn’t lose them, as they belonged to the people, I knew I had to do something with them,” Mehmeti said.

Twenty-five years after the war, he is finally ready to share his work, which he plans to include in a book he is trying to gather funds for, with photographs documenting the Kosovo war.

American actor Richard Gere visits Kosovo Albanian refugees at the Blace refugee camp in North Macedonia in 1999. Photo courtesy of Besnik Mehmeti

Born in Skopje, in what was then Yugoslav Macedonia, Mehmeti moved to London in 1993. In 1995 he began documenting the oppressive lives of the ethnic Albanian community in villages in North Macedonia, and the protests by Albanians in London in 1995, after turmoil erupted in Kosovo.

He returned to the region in 1998 during the Kosovo war, which culminated in NATO bombings from March to June 1999.

“When I came from London to Skopje, it was full of refugees from Kosovo,” Mehmeti recalled, explaining that he went to the Blaca refugee camps accompanying a Turkish journalist who had asked for directions “because I didn’t have any budget at that time”.

“When I saw that sea of people, it touched my heart deeply!”

‘Show the world what we’re going through’

Mehmeti remembers that he found it difficult to take photos of Albanians gathered in camps; for him, it was not easy to invade their privacy in that condition.

“When someone is crying and you invade their privacy in that state it gets on your nerves, making you wonder what you’re doing, who you are, why you’re doing this work, how you have the right to take away even that little dignity left for that person,” he said.

A case that stuck in his mind was when a woman pushed a little girl towards his camera to “show the world what they we’re going through”.

“The mother turned the child towards the camera and said: ‘My daughter, show the world what they are doing to us’,” Mehmeti recalled. He also has children who now are teenagers and do not like to be thrown to “face the camera, and cry”.

Nearly one million Kosovo Albanians fled to Albania, North Macedonia, and Montenegro in the spring and summer of 1999.

Kosovo Albanian refugees at the Blace refugee camp in North Macedonia during the Kosovo war in 1999. Photo courtesy of Besnik Mehmeti

Around 360,000 were placed in the Blaca and Stenkovac camps in North Macedonia and almost all of them left the country later that year.

They returned from the camps in North Macedonia after NATO troops entered Kosovo in June 1999.

An exhibition on a train commemorating the refugees who used it to escape Kosovo during the war in 1999 was inaugurated on the 20-year anniversary of the war in the Kosovo village of Bllace, close to the border with North Macedonia.

Beheaded and burned corpses

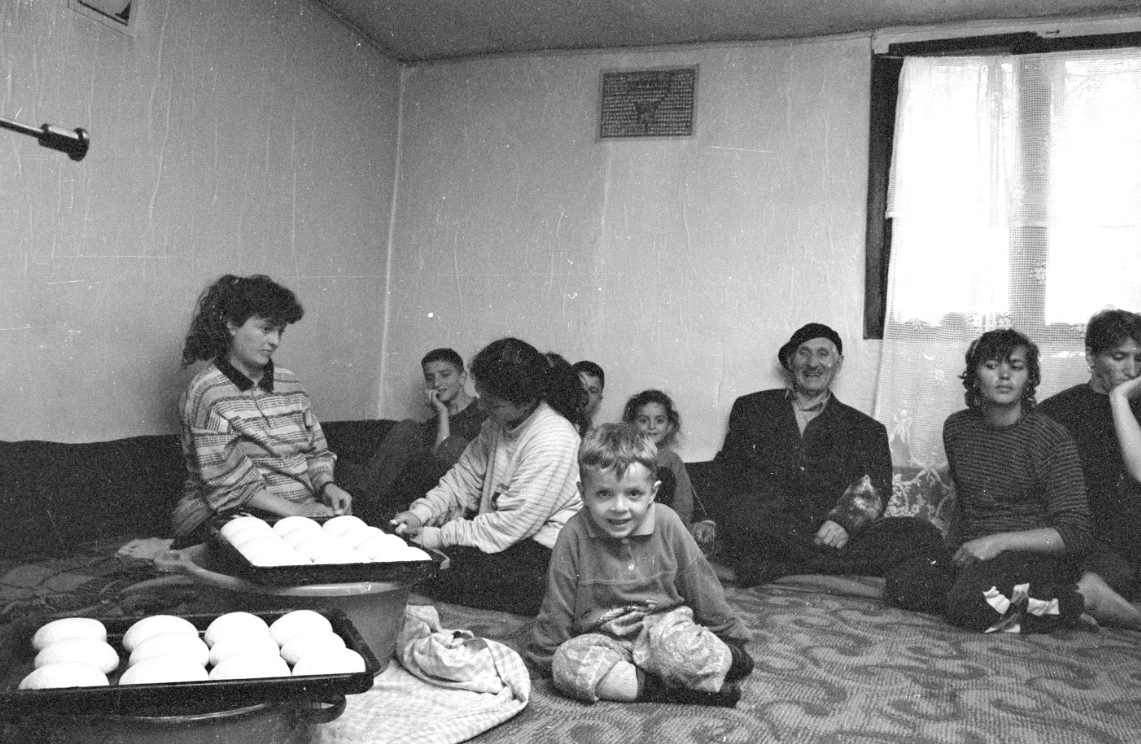

Kosovo Albanian refugees during the war in 1999. Photo courtesy of Besnik Mehmeti

In June 1999, as NATO troops entered Kosovo after three months of bombing, Besnik Mehmeti entered the country too.

He documented the condition of destroyed cities in Kosovo and vividly remembers the sight of burned corpses in houses in the countryside.

“Those who’d stayed in Kosovo began to come out of houses and show where the bodies were, and while I was there, I documented them,” he explained.

In one particular case, “I could not even think how to position the camera to frame the photo properly because the head was farther from the body”, he said.

Kosovo Albanian refugees in Cair, Skopje in North Macedonia in 1999. Photo courtesy of Besnik Mehmeti

In 1999, Mehmeti spent three nights at a Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, camp in Koshare, thankful that he’d managed to do what he always had wanted – document the ordinary lives of KLA soldiers.

“The atmosphere was positive, these young men could see their homes from the camp, and it gave them the will to fight,” he recalled.

Some of the most senior political and military leaders of the ormer Yugoslavia and Serbia were later tried and some convicted of responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Kosovo.

Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic was also charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity, but he died in prison in The Hague in 2006 before a verdict was ever reached in his trial.

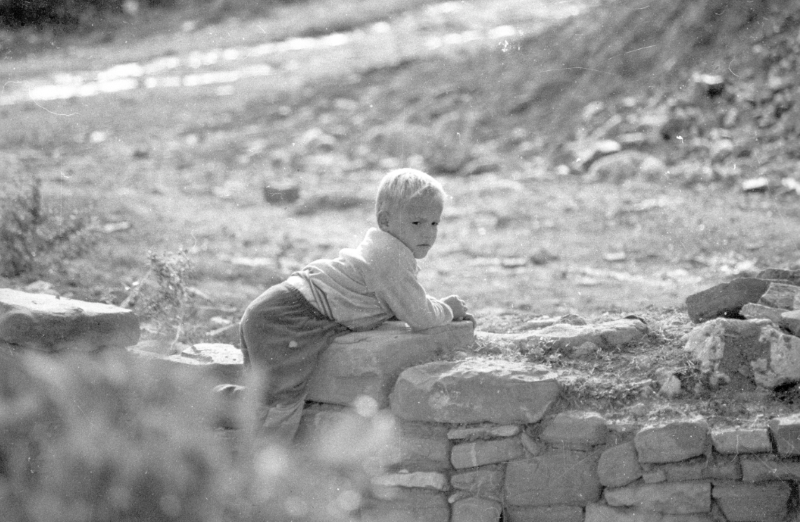

A Kosovo Albanian child during the war in 1999. Photo courtesy of Besnik Mehmeti