Although once progressive, today women’s magazines in Kosovo promote unattainable beauty, stereotypical gender roles, and glorify superficial notions of independence. But as content produced by and for women – they can and should impact social change.

In my early teens, I remember being obsessed with women’s magazines. I had my own large notebooks of magazine pieces glued into them. I remember being interested in the diverse beauty of the models and actresses features in these magazines, as well as stories and images related to health and fitness. I was criticized by my father for this newly gained obsession, but there was something fascinating about the women in the pictures and at that time I could not understand what that was. The images did not speak for themselves.

But now I think I understand what I loved about those women in my own improvised magazines as an early teen. They appeared independent and powerful, in control of their bodies and sexuality. But after digging into literature and critical media theory in particular, I understood that women’s magazines by and large promote glamour and often unattainable beauty standards in cooperation with advertising companies, creating stereotypical images of women and reducing them into specific gender roles. The approach is fueled by internalized sexism.

This is even starker in the slim pickings of Albanian magazines that cater to women – none of which actually can be called feminist.

I specifically looked into two women’s magazines in Kosovo, Kosovarja and Teuta due to their decades of popularity and publishing consistency. With the emergence of gender and feminist discourses among young women (and men) activists, I also looked into Flatra, another magazine in Kosovo that covers gender topics and is well known among readers, as well as an online self-proclaimed feminist magazine called Gentlewomen, launched recently.

Whether due to change of editorial policies or the world at large, the once progressive magazines have lost their emancipatory spirit entirely, while recent publication fail to grasp the contemporary struggles of feminists, including an understanding of how race, class, ethnicity, and sexuality intersect with gender identity.

Women’s writing

In “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Helene Cixous introduces ecriture feminine, or women’s writing, a project started by seven writers in 1970s, including Cixous, Luce Irigaray, Julia Kristeva and Catherine Clement. Women’s writing is about reclaiming the “feminine” from Sigmund Freud’s phallocentric theory in which women are written and interpreted by men, there is no female point of view or women’s expression of their individualities and subjectivities, and women’s sexuality is presented as inferior to men’s.

The first issue of Kosovarja, November 1971.

Through writing, Cixous claims, women shall learn to reclaim their autonomy since writing allows space for subversive thought. Both women and men can apply ecriture feminine into their work, and that means taking women’s voices and perspectives into account, their different contexts and backgrounds, as well as power relations and the deconstruction of the phallic. Therefore, by taking the power of writing, women can speak for themselves, can write themselves, and thus help liberate themselves and one another.

As texts about women and mostly by women, women’s magazines can have a great impact for social change. However, by looking critically into women’s magazine we are able to deconstruct womanhood, to reflect on its imagery and provide a feminist perspective that women’s magazine should reflect in order to contribute for the long-fought battle for complete equality between the sexes, for advocacy on women’s safety and institutional policies that make such attempts possible.

Stereotypical images of women

Women’s magazines worldwide are known for images of beautiful women on their covers. Flawless, young, and slim beauty has been celebrated for ages. Even Kosovo’s Kosovarja, Teuta and other texts about women in Kosovo’s press in general, associate a women’s magazine with physical traits and sex appeal. Once we get to analyze these magazines as texts, we see several stereotypical images of women. I noticed five of them: the privileged woman, the domesticated one, the marriage seeker, the beauty queen, and the damsel in distress.

The privileged woman is the success story of a celebrity, politician, businesswoman, or an important man’s wife. She is usually rich and stylish and a league above housewives or working class women.The housewife is addressed via the cooking recipes and ads that promote motherhood. The marriage seeker is the one to whom stories and tips on finding a match and proper behaviour that makes it happen are dedicated to. The beauty queen gets particular attention, both in terms of content and space. Sexy and thin models, Miss Kosova and Miss Albania, usually sell a brand and a load of physical appearance expectations for women as well. Whereas the damsel in distress is the one obsessed with her horoscope and fortune telling.

Conforming or confronting?

Kosovarja is Kosovo’s first magazine for women. It was first published in 1971 and strived for the political, social and economic emancipation of Albanian women. The content of the archived issues in the 1970s show that Kosovarja was an intellectual magazine that focused on politics, poverty and the hardship faced by Kosovo Albanians during the communist period, and reflected the interests of less privileged and suffering women. Particular focus was paid to the challenges of rural women and their lack of access to education and opportunities, as well as on young women’s student life. Texts about women’s health were elaborated in full. Additionally, advice on raising healthy children, cooking recipes and fashion constituted only a small portion of the entire text.

The archived issues I analyzed from the second half of the 1990s to the present day show an utter change in both form and content. While important sections from the 1970s issues included sections titled “Following the traces of revolution” and “Poetry,” today readers are provided with (among other trivial content) “The Sorceress,” a woman who predicts women’s fates, warns them about misfortune that might befall them, or keep them in suspense for exciting turn of events.

Issue no.10 of Kosovarja, 1972.

The covers of Kosovarja during Yugoslavia usually depicted women in a working place, in the mine; as musicians, warriors; and at times images of Kosovo Albanian women in traditional costumes would also appear. For almost two decades now, on the cover of Kosovarja we see actresses, models, beauty queens in sultry sexy poses. Be it the change of editors or editorial interests, or the submission to commercial forces which characterizes even most Western women’s magazines, Kosovarja was completely transformed from a political magazine to a pointless celebrity rag.

Teuta, named after the ancient Illyrian queen, first came out in 1994. The archived copies from 1994, ‘95 and ‘96 show a mixture of political content regarding women’s emancipation such as the struggles for independence and education. It also has sections devoted to traits perceived as “feminine,” such as fashion and cooking. These seem to have taken precedence since the first decade of 2000s to this day. Starting from the covers of Teuta – which always display a beautiful singer, actress or model – to the extended fashion corner, the pages were full of images, even for stories which in fact involved important topics.

Stereotypical images of women seem to be promoted constantly by Teuta.

I asked Teuta’s staff about the magazine’s mission. They told me they are using this medium to help address women’s challenges, improve women’s representation in the media, and insist on the idea that democracy makes no sense without women’s empowerment. This is all great, but this stated political aim does not reflect the magazine’s current content. The stereotypical images of women described above seem to be promoted constantly by Teuta.

The first issue of Teuta (1994) covered current affairs, culture and fashion.

In the summer issue, Sanije Gashi, Teuta’s editor-in-chief, claimed that despite the political hardships the country is facing, for summertime’s sake, the media should promote only positive news. Her approach sounds like a call for “Girls just wanna have fun,” but even Cindy Lauper has changed her lyrics from “Girls just wanna have fun” to “Girls want equal funds” referring to the struggle for equal pay for equal work.

Both Kosovarja and Teuta claim to be family magazines that address women’s issues in particular. Such a perspective is patriarchal since it sees women in the domestic framework. “Women’s issues are family issues” seems to be the message; not human rights nor social equality. Unless we’re able to see the fight for women’s liberation as a political one and keep the people who promote harmful messages and images through gendered marketing accountable, we will continue to write for many more decades and see no significant results.

Flatra's editor feared the exclusion of men as readers if they attach to themselves the feminist ‘label.'

Flatra magazine differs both in form and content from Teuta and Kosovarja. Flatra focuses on art, culture, psychology and gender issues. I asked Flatra’s editor-in-chief Bruna Merko about the magazine’s gender perspective. She claimed that particular attention is paid to men when the gender debate is discussed. Not only because men are part of the gender inequality problem, but because they aim to have both men and women as readers. Merko acknowledges the fact that it is journalists those who maintain the status quo in women’s magazines and do not follow the latest discourses on gender that aim at improving gender representation in the media.

When asked whether Flatra has a feminist perspective, Merko claimed that the magazine feared the exclusion of men as readers if they attach to themselves the feminist ‘label’. This is disappointing, considering Flatra is possibly the most intellectual attempt at women’s empowerment through mass media. Chances for changing patriarchal norms and humanizing gender roles are minimal when aiming a politically correct approach.

Gentlewomen, a recently launched online magazine, is a self-proclaimed feminist publication written by young female activists from Kosovo and Albania. In an attempt to create an equal and fair society, the magazine calls for sharing success and inspirational stories. Yet can sharing stories of success really work to challenge the inferior status of women in families, institutions, and society at large?

Along with the great enthusiasm of young feminist activists, a feminist magazine should have a feminist agenda – and that’s no piece of cake. It takes in-depth consideration of the interlinked social categories of gender, race, class and sexuality, and requires radical messages for reclaiming conventional notions of femininity and womanly attributes.

Gentlewomen's lack of a deconstructive approach resulted in racist remarks.

Gentlewomen lacks the deconstructive approach of these cultural and political phenomena, which has (unintentionally) resulted in racist remarks in one of its articles, in which the author claimed that violence was an inherent trait of dark skinned women (specifically Rihanna!).

I won’t even bother elaborating on certain ‘pink texts’ whose focus on fashion, beauty and motherhood tells all one needs to know about women’s total absence from political and public life, in decision-making and independence.

Sex and sexuality, or lack thereof

Content about sex and sexuality can be found in Kosovarja and Teuta, both during the 90s as well as 2000s, and continues to be present in these and other magazines today. But almost all of it falls into the category of tips, both in terms of reproductive care and sexual relations. Only occasionally, stories or articles on transgendered and homosexual men and women appear. Instead, there is no revolutionary calling on owning our bodies, our sexualities, on seeking pleasure and preserving that right.

I remember blushing and being confused about the “dark page” in Kosovarja. Those were two pages with dark background teaching about sexual pleasure. The content is not bad as such, and these pages were included even in the second part of the 90s. Kosovarja’s tips were about mutual pleasure, but the name of this section evoked mystery and if someone caught you reading it, you felt guilty.

Sex tips along with images of women in hard-core lingerie is not what women’s sexual liberation looks like. It took ages to destroy Freud’s theory on female sexual inferiority, to challenge the harmful notions of sexual differences in university publications and literature — still an issue at the University of Prishtina — and to debunk the myth of purity. But the struggle persists on the concept of sexual consent, on free reproductive choice, on LGBTIQ challenges and so forth. Sexuality is an integral part of the gender empowerment discourse. Yet, little to no space is given to sexuality in these women’s magazines.

Romanticized rape

As a teenager I remember the article “Who raped Doruntina” from a 1997 issue of Kosovarja. It told the story of an 18 year old girl who was raped by two men and committed suicide after that. It made me scared and angry. It openly discussed rape looks and its devastating consequences. The author asked “who the men were” and pled that the culprits be caught before they hurt another girl. It did not blame the victim, it did not call upon girls to be careful of what they wear and whom they talk to, it was about the perpetrator and rape as a crime.

On the contrary, today, if you look at the online version of Kosovarja, rape is romanticized, presented almost as drama or a ‘guilty pleasure’ topic we can read into and have something to share among social talks over coffee. Articles like “My father in law raped me while everyone was asleep” or “We met at a cafeteria, he took me to his place, raped me”, make rape sound a private issue, an individual experience of some careless, silenced girl or woman. Such articles should not be underestimated and simply deemed ‘bad press’ since they are contributing to ‘rape culture’, where men’s entitlement to women’s bodies is the norm, whereas women’s carelessness is to be blamed for, where the story ends in descriptive narration and has no calling against violence and abuse.

What should we do?

Women’s magazines should be anything but passive lamenting and superficial notions of independence. They must have a revolutionary and unapologetic approach. Stories should ascribe women agency in societal and institutional level, and the content should deconstruct power and the status quo of unequal gender roles.

Current magazines in Kosovo could claim to stand mostly for entertainment through ordinary topics that women and men might be interested in. But a 21st century magazine that stands for women’s empowerment does not make sense without a feminist perspective.

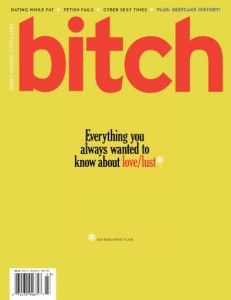

Bitch magazine reclaimed the offensive term. Photo: cover of bitch issue.

Think of Bitch Media magazine (reclaiming the “bitch” as a response to pop culture’s misogynistic use of term), Ms. Magazine (on the irrelevance of women’s marital status), Feministing (acting on revolutionary change of women’s status), Bust (entertainment from a feminist perspective), and so forth. The stories and images in these magazines seek to dismantle the very invisible forms of violence against women, be that sexism, racism or homophobia, it shall seek to challenge notions of femininity and masculinity and provide a perspective of liberty for all genders.

Such texts should be provided to readers in Kosovo as well. With the media contributing to the paradigm shift for gender representation, it could be possible for revolutionary texts to emerge among new writers and journalists. What better than to constantly come across messages and images that promote non-commercial images of womanhood and stereotypical gender roles, what better than to promote sexuality constructively, and with women writers and readers as key contributors in women’s increased literacy and empowerment?!

Since the 1970s, Kosovo women have been inundated with images of working women, housewives, patriots, beauty queens. Perhaps it’s high time for the radical women to take the floor.

Photo collage by Jeta Dobranja/ Trembelat.