Outraged by the terms of a border agreement with Montenegro, villagers on the border vow to take up arms if the government continues to ignore them.

To reach the remote villages spread out beneath the towering peaks of the Accursed Mountains, one has to climb the steep terrain and mostly unpaved roads off the main 28-km-long Pejë-Rugovë road that winds its way up through the Rugova Canyon.

On reaching the green fields of Haxhaj and Stankaj, on the border with Montenegro, where sheep and cows roam freely, an array of stone and wooden homes dot the hilly landscape. It is here that battles were fought to protect Albanian land from invaders and neighbors over the last half millennia.

While usually a joyous time, marking the celebration of summertime’s return from the cities to the highlands, many local communities now feel uncertain about the fate of their ancestral homeland, straddling the historically significant Kosovo-Montenegro border.

“The people have been left alone like a little infant without its mother or father, like an orphan – that is how Rugova has been left,” says Ali Hajdaraj, 57, a Rugova highlander from Haxhaj village, speaking about the latest strife plaguing this part of Kosovo.

Ratification of the border demarcation deal with Montenegro, which the EU has set as a condition for visa liberalization, is a controversial issue for the highlanders as well as for the opposition parties who claim that Kosovo will lose more than 8,000 hectares [20,000 acres] of land along a stretch of land spanning more than 60 kilometers if the Kosovo parliament ratifies the agreement.

Border demarcation talks between Kosovo and Montenegro began in 2011.

Ali Hajdaraj, a Rugova highlander from Haxhaj village, points towards where the new border with Montenegro will be. Photo: Valerie Plesch.

More than a hundred kilometers away from Rugova, anti-government supporters have protested regularly on the streets of the capital, Prishtina, and inside parliament over the last year.

The protests, organized by the main opposition groups, contest the Agreement on the State Border signed by Kosovo and Montenegro in August 2015 in Vienna, as well as an EU-brokered deal with Serbia on the creation of an association of Serbian municipalities, also signed in August 2015. The opposition seeks a review of the agreement and the dismissal of Murat Meha, the commission’s chair.

“The Kosovo government has brought the border to our front door. But what sane person agrees with Montenegro without consulting with us, the people who are here?” a frustrated Hajdaraj said from his home in Haxhaj.

“They have taken away land that been passed from father to son for generations; we have graves here, the graves of our forefathers who fought on the other side of the border,” he adds.

Meha insists that the government’s commission on border demarcation held more than 20 meetings with villagers from the Rugova region and with mayors of the four affected municipalities.

“We searched all official, legal and technical documents from both Kosovo’s and Montenegro’s territory. Based on these documents, Kosovo does not lose any land in this region because all documents met mathematically in one line,” Meha said in an email statement.

He added that his commission “has done its job with the utmost responsibility, based on the law and official documents, without making any mistakes.”

Hajdaraj and his fellow villagers are eager to show outsiders the location of the proposed border, a short jeep ride through a creek and a wooded path a few hundred meters away from his home.

Locals here say they have seen Montenegrin police patrolling the woods here in recent weeks. They are afraid to let their sheep graze the fields beyond the hills, as they fear that either the Montenegrin or Kosovo police will confiscate them. One Haxhaj villager, Zog Selmanaj, 55, said the Kosovo police fined him 80 euros ten years ago for crossing the invisible borderline near his home while looking for his sheep.

“This issue is not just about a group of people whose property will be violated, we’re dealing with the definition of the state border, which must not be done under pressure,” Fatmire Kollçaku, vice-president of the opposition Vetevendosje party said in an interview in her hometown of Pejë, the municipality that includes the Rugova Valley.

“It’s a pity that demarcation with Montenegro is also a criteria for [EU] visa liberalization,” she said, noting that other states in the region like Slovenia and Croatia did not have border demarcation deals set as a prerequisite for joining the EU; they are still working to resolve border disputes between their countries.

Kosovars are now the only people in the Balkans who still need visas to travel to countries in the EU’s Schengen zone. In May, the European Commission proposed visa-free travel for Kosovars, but on condition that Kosovo does more to fight organized crime and corruption.

Far from the debating chambers of the Kosovo Assembly, families who have lived in the remote Rugova highlands for centuries are not ready to give up their land for political gain.

Stankaj is one of the last villages in this part of Kosovo, where around 50 homes are scattered across the steep hills. There are no schools or markets here, which is why families along the border retreat to Pejë and its surrounding villages for most of the year, mainly during the cold months.

Balë Ali Hysnikaj stands near his home in the village of Stankaj. Many generations of Hysnikaj’s family have lived in this part of the Rugova Valley. Photo: Valerie Plesch.

Balë Ali Hysnikaj, 69, had just returned to his farming village of Stankaj for the summer with his wife a few weeks ago and was eager to get back to his fields and cows. Like many Rugova highlanders, dispersed throughout the valley, many generations of Hysnikaj’s family have lived in Stankaj.

“We’ve been here for centuries,” he says, referring to his ancestors buried at the Kulla tower of Mokra, one of the reference points along the Kosovo-Montenegro border.

“The border line is getting very close to our village,” he adds from his small wooden home nestled on a hillside, overlooking the Rugova Valley. A small man with weathered hands, Hysnikaj wore an American flag across his back and joined other highlanders to march in the last protest against the border demarcation deal in Prishtina in April. He is baffled by the government’s unwillingness to reexamine the available documents and maps before proceeding with the demarcation deal.

Many of our forefathers died over the years, protecting the border. If they ratify this deal, I swear the next day you’re going to hear gunshots.

“They must be getting something out of this, and now they’re trying to repay it,” he says. “Something is not right.”

Back in Haxhaj, considered one of the villages most affected by the border deal, Hajdaraj says he and his comrades will even start a new war if the deal is passed in Prishtina.

“Many of our forefathers died over the years, protecting the border [at Cakorr],” he says. “If they ratify this deal, I swear the next day you’re going to hear gunshots. Haxhaj is the most affected region. That land is precious.”

Unlike some highlanders, however, Hajdaraj has refused to take part in any protests sponsored by political parties, including the last anti-government protest organized by two of the three main opposition parties, the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo, AAK, and the Initiative for Kosovo, NISMA.

“They [the government] are playing with us. They are traitors to the Albanian nation,” he says.

“This never happened anywhere else in the world except here,” he adds. “How come Montenegro has the right to come miles inside Kosovo to take our land?”

Ali Hajdaraj and Zog Selmanaj, Rugova highlanders from Haxhaj village, stand by a creek that leads towards the new border with Montenegro. They have seen Montenegrin police patrolling this area in recent weeks. Photo: Valerie Plesch.

To address the border issue and the highlanders’ concerns, the municipality of Pejë put together a commission in 2012 to represent the villagers. One of its members, Sadri Zekaj, represents 35 villages in the Pejë region, including Decan and Rozaje – the official border crossing with Montenegro.

Zekaj says if parliament ratifies the border demarcation, the border with Montenegro will be pushed inside Kosovo by at least six-and-a-half kilometers on the Pejë to Rozaje road, which is a vital gateway and a border crossing for vehicles traveling to Western Europe from Kosovo.

The territory between the two checkpoints, Rozaje [in Montenegro] and Kulla [in Kosovo], is contested. Montenegrin border police already patrol the land here, although the demarcation agreement has not yet been ratified.

An ad-hoc international commission sent by former President Atifete Jahjaga last March to assess the demarcation deal did not produce favorable results for the highlanders.

Some experts say the commission wrongly relied only on cadastres to draw the new border, which goes against standard criteria of international law used for border delimitation.

“They went straight to demarcation, using cadastres as reference points, to define the Kosovo- Montenegro border,” says Enver Hasani, an international law expert and former president of the Constitutional Court. Hasani says the committee should have considered maps, economic interests and the configuration of the land as well.

Meha, chair of the government’s commission, said documentation containing information on the cadastral boundaries, boundaries of municipalities, as well as different topographic maps, were all taken into consideration.

But Zekaj says this is the only case in Europe where cadastral documentation alone was used to set a border. “For the first time, Montenegro will have the view over the Kosovo plains,” he adds.

Another member of the commission, Ali Lajqi, former mayor Pejë, wants to bring the borderline back to Cakorr and Kulla. “The Montenegrins know the borderline very well but of course Montenegro prefers this new version of the border,” he says.

“The reason why this process is happening like this is that Montenegro is assuming that we don’t mind losing our land just to join the EU,” Lajqi adds.

One Rugova highlander who has been fighting this border battle for almost the last five decades is Zeqir Dreshaj.

Zeqir Dreshaj holds a book with a photo of Jakup Ferri, an Albanian nationalist and rebel leader from the 1880s who died in a battle against Montenegrin forces. Photo: Valerie Plesch.

He is one of the most prominent and outspoken activists on the border demarcation agreement.

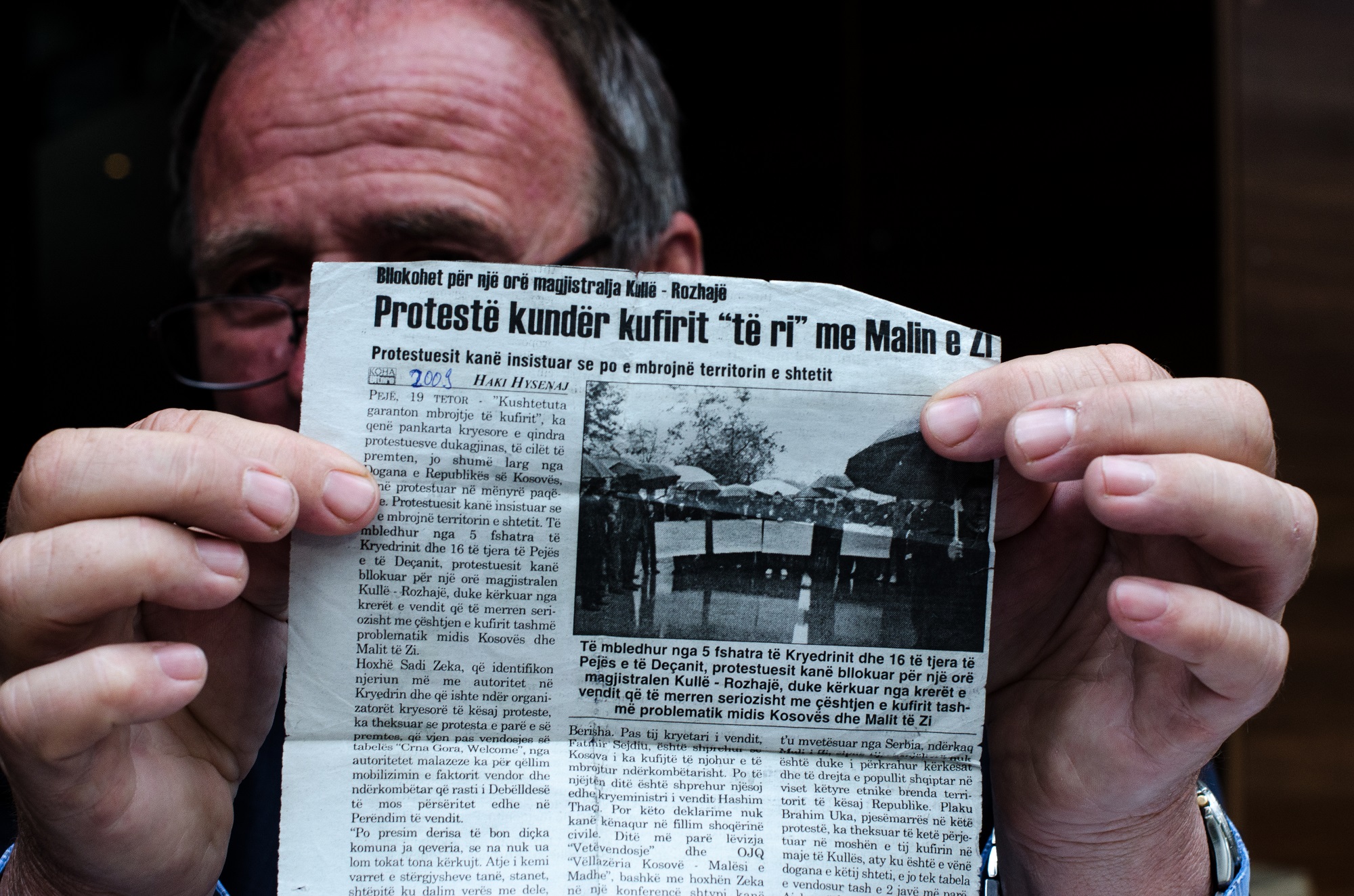

From his winter home, which he shares with his wife and grandsons in Naberxhan, on the outskirts of Pejë, he keeps an archive of books and photocopies of old photos from the Rugova Valley and newspaper clippings about the border dispute.

One photograph found in Dreshaj’s metal suitcase, taken in 1900, shows Albanian fighters in traditional dress protecting the Cakorr border. Dreshaj still wears a traditional white turban typical of the Rugova region, called a maud, and recalls staying in his village of Kuqishte near the Rugova lake during the winter as a child.

Now 85 years old, Dreshaj says he will not give up the fight to protect his land.

“All my forefathers fought and died there [in Cakorr] protecting that border for 500 years. I have to do it, too, because I must. I also have to think about my [grandsons]. I have to do it with all my flesh, blood and soul,” he says. “We can’t give up because it is our land.”

Dreshaj counts on the international community – not the Kosovo government – to resolve the border issue, by keeping the current border at Cakorr, which he says is based on the 1974 Yugoslav constitution.

The border crisis with Montenegro most likely will not be Kosovo’s last. Kosovo also shares a 300-km border with Serbia and experts like Hasani fear what will happen if Kosovo only considers cadastres for future demarcation agreements.

There will be a big trouble. Montenegro is the tip of the iceberg of what may happen.

“There will be a big trouble,” he says. “Montenegro is the tip of the iceberg of what may happen, and this is my main concern.”

Tomor Cela, a GIS expert and geographer, does not agree, however. He conducted an independent analysis of the results presented by the Kosovo State Commission for Marking and Maintenance of the State Border, the commission appointed by former president Jahjaga.

He concludes that the use of cadastres to define the border was correct. “If the administrative and cadastral criteria are removed from the system of the demarcation of the border between Kosovo and Montenegro, it will create a very dangerous precedent when it comes to defining the border with Serbia,” he says.

“Serbia might then ask for the administrative and cadastral data to be eliminated, arguing that those data were not used to define the border with Montenegro – and the border [with Serbia] might then come as close as to the Ibar river,” Cela says in Prishtina, displaying various old maps of Kosovo and Montenegro from the last half-century.

For now, the government seems intent on pushing forward. President Hashim Thaci recently told The Wall Street Journal that “Brussels literally has no more reasons to delay” when it comes to scrapping visas for Kosovo, adding that he will make sure the Kosovo parliament ratifies the border agreement with Montenegro before the summer is over.

That does not sit well with the highlanders. “If they ratify this agreement, the people will start a war here,” Hajdaraj warns.