For the children of Kosovo Albanians seeking refuge from the war in neighbouring countries, improvised classes offered hope amid hardship – and a rare feeling of safety.

As war raged in Kosovo following the start of the NATO air strikes campaign against the Yugoslav military on March 24, 1999, for many children, education continued in refugee camps across North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Albania.

Some studied in tents, others in the borrowed classrooms of school facilities nearby.

The makeshift classroom where Zahiri found himself was nothing like the one he had left behind. It was a large green tent filled with donated toys, where international volunteers tried to create a sense of normalcy for children who had seen too much.

“For us kids, it was everything,” he says. “It was the only thing that made us feel like children again. We kept going to the school, as everything was normal.”

‘Hope – when everything else felt lost’

Ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo sing songs at an improvised school in a refugee camp near the village of Neprosteno, North Macedonia, May 1999. Photo: EPA/MLADEN ANTONOV/MA-FOB.

When war forced thousands of Kosovans to flee their homes in 1999, education became an afterthought. Survival was the priority, while for many children adapting to new environments and societies came with challenges.

Arbenita Miftaraj, from Runik in the Skenderaj/Srbica area, now a teacher herself, vividly remembers the day she heard about the classes while staying in Kukes, northern Albania.

“I was so happy, and you know what? I didn’t even have shoes. But the desire to learn overcame the problems and challenges of that time. I waited for my sister to finish her lessons, took her shoes, and then it was my turn to go to the classroom in the tent,” she says.

Like most others, her family had fled Kosovo with little more than the clothes on their backs.

“I didn’t know about Luli i Vocërr, by Migjeni,” she says, referencing a famous poem about a poor child struggling through life. “Now I realise how much I resembled that character.”

After a month in Kukes, her family was relocated to Durres, on the Albanian coast, where she continued her education until June 1999.

“I never thought we would return to Kosovo,” she reflects. “But school, in whatever form it came, was a turning point. It gave me hope when everything else felt lost.”

Today, as a teacher, Miftaraj carries those memories with her, knowing firsthand the power of education in the darkest of times.

“Even now, those emotions follow me,” she says. “The war left its mark, but so did the lessons I learned.”

For many refugee children, school became a rare source of stability in a time of upheaval.

Lejla Zeqiraj Ademaj, from Istog/Istok, was in fourth grade when her family fled to Rozaje in Montenegro and she started lessons in the Mustafa Peqanin school.

“As soon as we learned that a school had started for Kosovo refugees, my father immediately sent me to the fourth grade and my brother to the second grade,” she says.

“I still remember my teacher’s face and the friends I made. We were all connected by the same fate. We were children with dreams who had been through hell yet still held onto hope,” she adds.

Ademaj still remembers a poem, Vesa mbi lule (“Dew on the flowers”), which reminded her of Kosovo. “It ended with the words: ‘Beside you, I wish to lay and die.’ After reciting it, we would cry, longing for our homeland,” she continues.

Aid from international organisations was also a highlight at that time. “I eagerly awaited the words ‘Help has come!’ as we rushed to the aid distribution points.”

She remembers how an elderly man who used to sell ice cream usually gave it to the Kosovo refugee children for free.

Books and lessons offered comfort and escape

Lorika Govori. Photo courtesy of Lorika Govori

Adapting to a new environment and social circles was challenging for many children. But most never spoke about it, as it felt insignificant compared to everything they had already endured.

Lorika Govori, from Prishtina, was just 11 when the war forced her to start her fifth grade in a school in Llakavic, a village near Gostivar, in North Macedonia.

“As an extrovert, I knew I had to adapt quickly. For me, school became a safe haven. Surrounded by books and lessons, I found comfort; it was a way to escape thoughts of loss and the uncertainty around us,” Govori says.

One of the toughest experiences from that time was dealing with her Macedonian language teacher.

“She warned me that I would have to repeat the year. For a refugee child who had already lost everything and was struggling to survive, it was a devastating threat,” she says. “I told no one, not even the family that had taken us in. I was afraid; I didn’t want to cause more problems.”

What happened next was unforgettable: “One day, the teacher expelled me from class. But as soon as I stepped outside, all my classmates followed. They refused to accept that injustice.”

Trauma has shaped adult lives

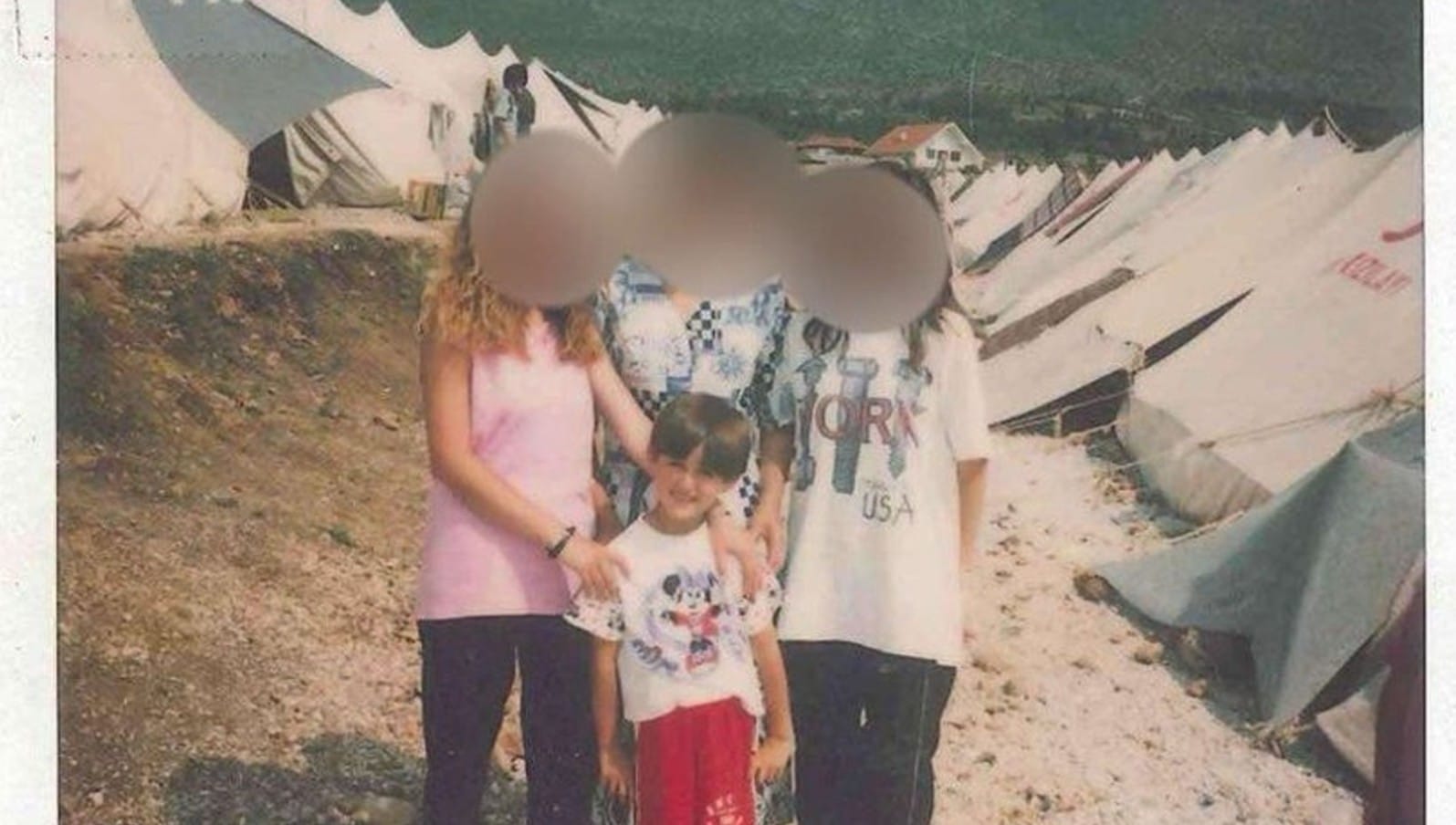

Blerton Zahiri in a refugee camp in North Macedonia in 1999. Photo courtesy of Blerton Zahiri

For many children, the trauma of war has followed them into adulthood, shaping their careers, personalities and self-confidence.

Blerton Zahiri recalls how travelling by bus would trigger memories of his journey as a refugee.

“For a long time, bus rides reminded me of being displaced during the war – the fear that something terrible would happen,” he says. “Even summer storms would bring back memories of our temporary ‘home’ in Bojane.”

“Now, when I see wars continuing around the world, it feels like déjà vu,” he says.

Shqipe Rafuna Bajra, from Prishtina, was 17 when she found herself among hundreds of thousands of Kosovo Albanians in North Macedonia in April 1999.

A family in the village of Reçicë e Madhe took her family in and she completed her third year of medical school there. “I felt unmotivated as I had no idea what would happen to us next,” she recalls.

“Experiencing war as a highly sensitive child left a deep emotional impact on me. My mood would shift suddenly, and I often found myself crying,” she adds.

Edona Shehu-Hoxha, from Planejë, Prizren, who was only nine when her family took refuge in Krujë in Albania, struggled to adapt. She barely attended school.

“I was in second grade in Krujë but only managed about three weeks because I couldn’t adjust or fully understand the dialect,” she remembers.

“They gave us colouring sheets to draw our memories of home and the day we left. For me, it triggered trauma, I felt awful.”

The experience stayed with her long after returning to Kosovo. “For a long time after we came back, I could barely raise my hand in class to answer a question. It took me until university to find the courage to express my thoughts clearly,” she adds.

‘It made our generation stronger’

Ethnic Albanian children, refugees from Kosovo, read school books during a lesson in the Macedonian capital Skopje, May 1999. Photo: EPA/GEORGI LICOVSKI/MA-FOB

Forced into exile as children, for many the refugee experience was about more than just survival; it shaped their identities, careers and sense of duty to the future.

Zeqiraj-Ademaj believes the refugee experience toughened their generation.

“Despite the suffering and hardships, we learned a valuable lesson – to be humane in times when a nation needs help. It was a difficult time but it made our generation stronger,” she insists.

Zahiri, now working in management and retail, says everything he went through instilled in him a responsibility to study and work hard.

“Returning to Kosovo was a strange mix of fear, joy and sorrow. We didn’t know what awaited us. Seeing our homeland reborn from ruins, the silence that resembled an abandoned city. That image stays with you,” he says.

“The lingering uncertainty follows you forever. It instills a deep responsibility – to study, to work hard and to contribute to building a brighter future,” he continues.

Lorika Govori’s experience of a refugee childhood has also stayed with her.

“This has followed me throughout my life – a painful lesson in injustice and discrimination but also a powerful memory of the solidarity and support from my peers,” she says.

“It wasn’t just a personal struggle; it was a painful part of our collective history as refugees,” she concludes.