Legacy of Kosovo war and continued tensions between Kosovo and Serbia have not stopped two young people from building a life together in Prishtina.

For two young people from enemy countries who were two years old during the Kosovo war, the painful past, bad relations between the two countries and ongoing tensions have not stopped their love for one another.

For Suzana Maric, 25, from Novi Sad, Serbia and Gent Sejdiu, also 25, from Ferizaj, Kosovo, centuries-old enmity and a bloody war have not been an obstacle to living together.

On the contrary, they consider that these issues have helped them learn more about both narratives about the war.

“I am not very typical, I will not defend the [Serbian] regime. The regime of the 1990s, Milosevic’s regime, for me was like Hitler’s regime in Nazi Germany, a regime that brought a lot of terror, a lot of bad things,” Maric said.

Little is discussed in the public in either country about possible marriages between Kosovars and Serbs, after the great societal division that the war in Kosovo left behind. Both societies see such ideas as a forbidden apple.

But Suzana and Genti told Prishtina Insight they have closed their ears to societal prejudice and politics to build a common life.

“Even before I met Suzana, I was not against marrying a Serb. Suzana became my destiny and I started a new life,” Genti Sejdiu says.

They have been living together in Prishtina for a year, despite the prejudices and historical circumstances. Both of them considered their relationship from the beginning of cohabitation as a marriage, which they plan to crown with children.

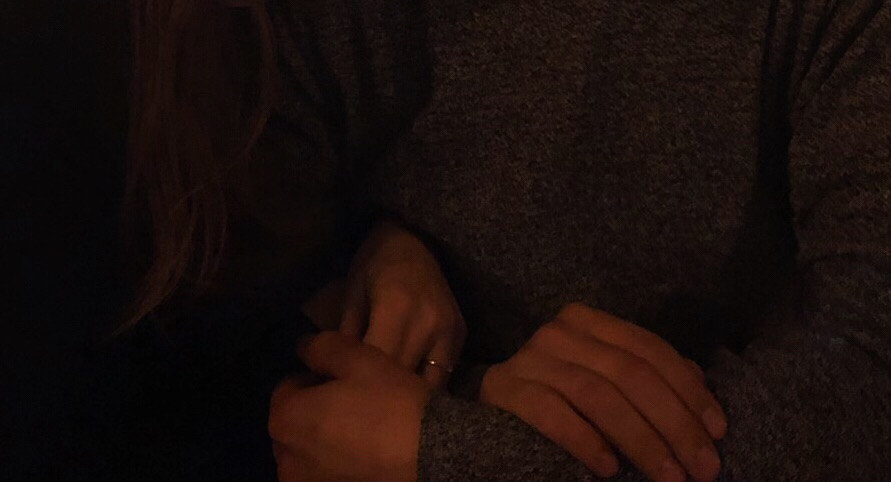

Suzana Maric and Gent Sejdiu. Photo: Antigonë Isufi/BIRN

The narrative about their acquaintance and connection is built on two characters who have accepted each other and who decided to return from the countries where they were working abroad to live in Kosovo.

“For me it was not hard to accept our relationship because I was working with Bosnians and Serbs and so many people from other countries. I already saw what culture they have, both the similarities and differences. I saw we are not so different, so it wasn’t hard for me. I have never had a problem with Suzana’s ethnicity,” says Sejdiu, who works as a builder.

Maric and Sejdiu lived for several years in Slovenia where they had worked temporarily outside their professions. They met by chance on a beach near Rijeka, in Croatia.

“It is very hard to incorporate in their [Slovenian] society. I worked there in a hotel, and I didn’t like it because we were marginalized and weren’t part of society. So we came to Kosovo and found jobs and I started to study at the University. I studied law in Serbia but I didn’t finish,” Maric recalls.

In Kosovo, Suzana has started studies at the Balkan Studies Department at the University of Prishtina and at the same time works at the organization Youth Initiative for Human Rights.

She left Novi Sad to come live with Genti, and the only Kosovo document she has is the faculty ID, while she works with a temporary permit.

“I didn’t want to work in the law system in Serbia and with a law degree, outside of the country you can’t do anything. So now I’m focused in Balkan studies, and I love it, because I can be a translator or a professor,” she adds.

Neither society accepts Kosovar-Serbian marriages

It is very rare in Kosovo to hear about mixed Kosovo-Serbian couples. The tense situation between the two states, the different narratives and the failure to confront the past that would lead to reconciliation, make it almost impossible for people to bond in the institution of marriage.

Some 23 years after the war in Kosovo ended, the topic remains taboo and there is little research on it. Marriage between Kosovars and Serbs is not encountered in public discussions, being seen as prohibited and almost impossible.

Anthropologist Angjelina Hamza-Hasanaj, who studies mixed marriages, says that without touching on the political issues between the two states, she sees the union of these two parties in one family as early.

“Today, if such a marriage takes place between two people from enemy nations, if we stop and analyze it in the cultural context and in any other context, it means a lot,” Hamza-Hasanaj told Prishtina Insight.

Prishtina Insight asked both Kosovar and Serbian families in Kosovo about it, and most hesitated to speak, describing such marriages as a thing that “cannot happen”.

“Even in a dream, if I saw my daughter or son marrying a Serb, I would go crazy. I would never forgive it,” said Lumja from Vushtrri, a mother of six children.

Hamza-Hasanaj says marriage is a very important phase of the life cycle and its realization is important not only for the partners but also for the family and society in general.

“These marriages affect a wide dimension besides the family; they also affect other dimensions of life, both socio-cultural, economic, political and legal,” she adds.

Hamza-Hasanaj considers that a decision for such a joint marriage depends on the determination and agreement of the couple, and on what basis, cultural or otherwise, they want to build their lives.

About six families from both sides told Prishtina Insight that neither society is prepared for a marriage which unites two enemy peoples in one family.

“As long as the consequences of the last war are still fresh in the Albanian families of Kosovo, if we take as a concrete example the massacre and the missing in the village of Mejë, where there are families that have still not yet found their loved ones, without going into details, I can say that this has made it difficult and unacceptable to accept such marriages,” added Hamza-Hasanaj.

Kosovo Serbs in Prelluzhe of Vushtrri and Zubin Potok also said they would not welcome a marriage with Kosovars.

“It is not possible as long as I am alive. I live in Kosovo, but I would never accept a Kosovar as part of my home,” said Dragan from Zubin Potoku, father of two daughters and a son.

However, Genti and Suzana say that they have not encountered any obstacles from their own families, and, as for society’s prejudices, they have turned a blind eye to them.

“My mother doesn’t divide people by nationality or religion. She has Albanian friends, Bulgarian and different ethnicities, so I learned not to divide. I learned to watch how a person is, whether good or bad, what the habits of that person are, their character – those things I learned to divide, but only those,” says Maric.

“When my mother met Gent, she liked him immediately, because he was good and had good character and was polite and clean. My family wants us to go to them for New Year,” she added.

Some Kosovar families consider that as long as the fate of the missing, rapes, murders and other losses in the Kosovo war is not clarified, marriages between Kosovars and Serbs cannot take place.

But Genti says that while at first his father had a problem accepting Suzana, when he got to know her he completely changed his opinion. However, for his mother, communication remains a problem because they do not speak a common language.

“It is not good for society to judge us, because we are the post-war generation. When I started this relationship, I thought: Why waste my life on somebody’s judgments and what people think? This is my life and not theirs so I didn’t care at all,” he says.

Most mixed couples date from the Yugoslav era

Most Albanian-Serbian couples are now in their 60s, married in an era when secular communism crossed ethnic and religious divides.

Unlike after the war in Kosovo, during the time of Yugoslav communism, there were more marriages between people of different ethnicities, especially between people who belonged to the political or cultural elites.

Some of the cases that remain in the collective memory are the marriage of the actor Bekim Fehmiu and Serbian actress Branka Petric, from whom they have two children.

Another public case was the marriage of the actor Faruk Begolli with the National Theater of Belgrade ballerina, Zoja Dokovic, who divorced after 17 years of marriage.

In addition to artists, some Albanian politicians were married to Serbs from Kosovo in the 1980s, such as former President of the Presidency of Kosovo, Ali Shukrija. Besides them also Alush Gashi and Halil Fejzullahu.

In 2019, on the other hand, according to the Statistics Agency of Kosovo, there were only six marriages between Albanian men with Serbian women and one marriage between a Serbian man and an Albanian woman.

In 2018, there were five marriages between Albanian men with Serbian women and six marriages between Serbian men with Albanian women.

In 2017, there were two marriages between Albanian men with Serbian women and two between Serbian men with Albanian women; in 2016 there were six for both sides.

Institutional struggles over documents

Suzana and Genti say their marriage is being hindered institutionally because the institutions of both countries do not accept each other’s documents, while on the other hand they want their marriage to be legally crowned.

“The biggest problem we have is with documents. The young are suffering and the politicians are joking with us,” says Maric.

Anthropologist Hamzaj says politics plays an important role in the lives of peoples of the Balkans.

“How long it will be before there is social coexistence between the two states is a question. Obviously it will take years, and this issue remains to be seen and researched continuously,” she added.

On other hand, Genti and Suzana say that they do not believe that such politics works for the good of people.

“We don’t even have a television in our house because we don’t want to deal with these issues. If there is a war, we will see it on the street. Everything is propaganda, what we hear, what we see and everything else. In this century, it is very difficult to distinguish between manipulation. Politics cannot tell me where to stay, where to live and what to eat. End of story,” Maric concludes.