A wall erected Sunday on the banks of the Ibar river stirs debates on the details in the Brussels-negotiated plan to remove barriers to free movement on the Mitrovica bridge.

Mitrovica, Kosovo — All morning on Friday the Mitrovica Bridge, as it has done for more almost two decades, drew the attention of the inhabitants of what was once a united city. In the northern part, inhabited primarily by Serbs, residents made their way over the rocks on the unpaved Kralja Petra street, which has been under construction for one month as part of a deal made in Brussels to pedestrianize the street. They walked past yellow excavators and men working towards the end of the street, where the Ibar river bridge separates north and south Mitrovica.

Less than 50 meters away, a steady stream of people coming from the Mbreteresha Teuta boulevard crossed the bridge, recently paved to make way for it to be open to traffic once again after many years of hosting only pedestrians, cyclists and KFOR tanks.

They peered through a temporary steel fence on the north end of the bridge to examine the latest source of consternation for this deeply divided city: a cement wall in the shape of an arc, about two meters high. Throughout the morning and afternoon, curious Mitrovicans from both sides kept coming to peer at the progress and then turn back.

“This is nothing but stupidity,” complained Slobodan, 23, as he watched inspectors, elderly men and journalists mill around the wall.

“Are they going to put up a Chinese wall?” he said, referring to the Great Wall of China. “There’s a Chinese wall, a Berlin Wall, and now the Serbian wall.”

Northern Mitrovica and the steel bridge over the Ibar river have long been a sore point of Prishtina’s efforts, now mediated by Brussels, to bring the entire territory of Kosovo under their control, a process that has long been resisted by the majority of its residents.

In November 2013, as part of the landmark April 19 deal of the same year reached between the Kosovo and Serbian government, the four predominantly Serb municipalities held elections under the Kosovo system for the first time. The four northern municipalities have since joined Kosovo’s governance structures, though Serbian structures also persist.

For years Prishtina and international actors have sought also to see vehicular traffic moving across the bridge, which had been blocked by a large barricade since 2011. The barricade came down in 2014, but in its place a so-called “Peace Park,” a row of cemented flowerpots in the middle of the bridge, was placed.

In June 2015 both sides agreed in Brussels to renovate the bridge and turn Kralja Petra street into a pedestrian zone. The bridge has often become a spot for friction or discord and is a sensitive topic in Kosovo, especially for Mitrovicans, as it has been the scene of some violent incidents, including in April 2015, when an ethnic Serb teenager was stabbed in the chest.

Dragan Spasojevic, Chief of the municipal department of Urban Planning Construction and Housing Affairs in north Mitrovica, told Prishtina Insight that the wall was “clearly agreed upon” in Brussels, something that Kosovo Minister for Dialogue and south Mitrovica mayor Agim Bahtiri both deny.

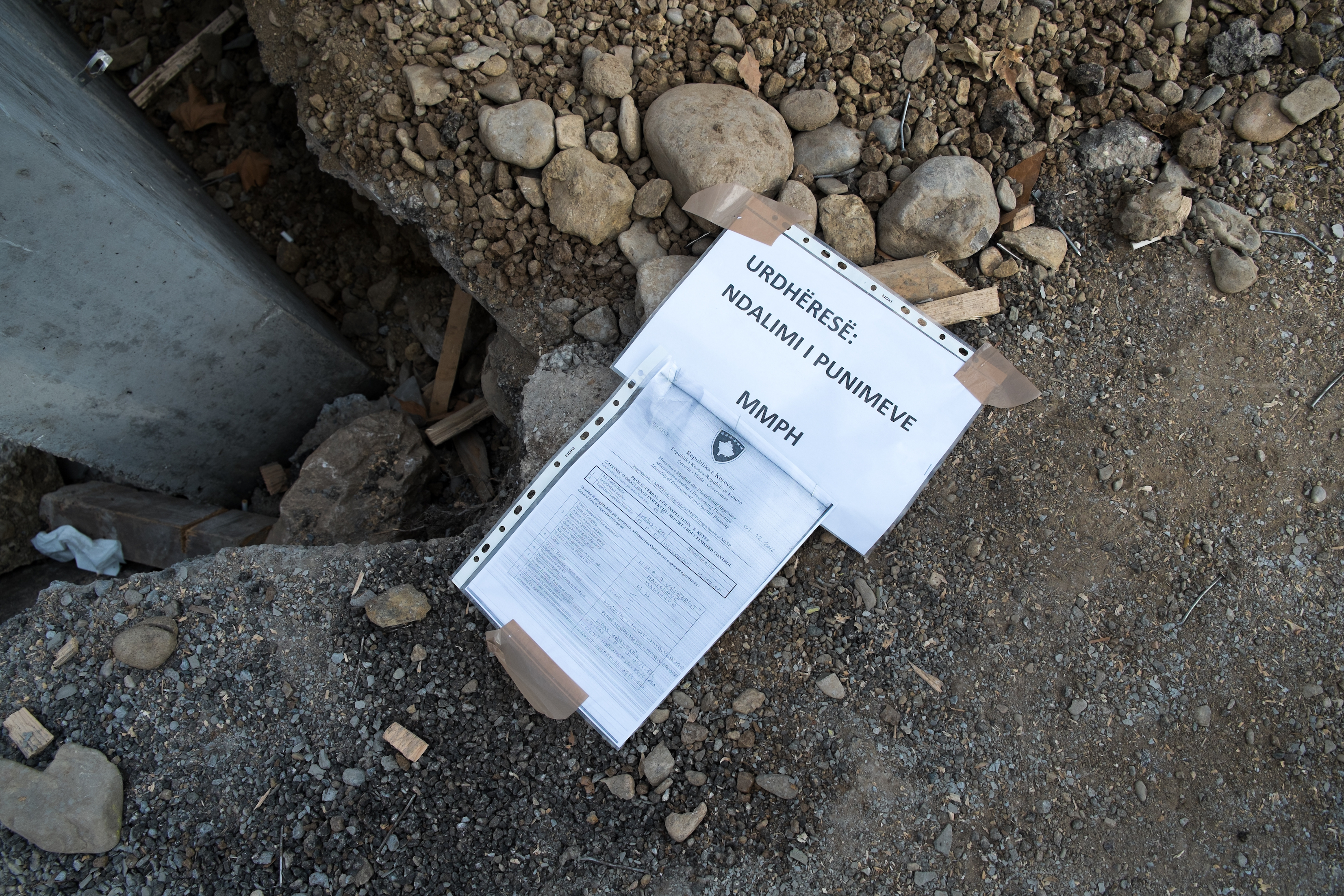

On Thursday, Kosovo’s Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning ordered a halt to the works and said the wall must be torn down. However, North Mitrovica mayor Goran Rakic told PI that a solution was reached on Thursday evening at a meeting in Prishtina with high-level EU officials and Kosovo Minister for Dialogue Edita Tahiri. According to people party to the negotiations, the wall was to be torn down this morning, but Mr. Rakic said otherwise.

“We agreed to redesign the wall into an amphitheater so that it can be a summer theater open to citizens from both sides of the bridge,” he told PI. “It will not be a wall.” When asked if the amphitheater would face north or south, Rakic said it would face both sides.

He also maintained that this will not be another temporary fix like the “Peace Park.”

“This will be the final agreement,” he said. “It will protect the pedestrians from the traffic.”

“The bridge and the wall are fine, they are infrastructural improvements changing the wall for the better,” Spasojevic, the municipal urban planning chief told PI.

“Whoever looks upon this as a wall sees something that divides, but whoever looks at this as an amphitheater sees something that connects, because I believe this amphitheater will one day be used by Serbs and Albanians.”

Among the citizens from southern Mitrovica who came to examine the construction was South Mitrovica Mayor Agim Bahtiri, who was also present at the meeting on Thursday in Prishtina.

“We’re working closely with the EU and Mr. Rakic to stabilize the country and the city. I believe that it will be stable very soon. This is something that took us by surprise. But we agreed yesterday that we will stop such things, because we want a stable city, a European city, which will belong to all citizens — a united city.”

Bahtiri says the wall was not discussed in Brussels.

“This wall is absolutely not part of the Brussels dialogue and needs to be torn down and the entire Brussels plan is being finished. But the wall needs to be torn down.”

Prishtina Insight has the original plan for the area’s “rejuvenation” and it does include a low wall. From the drawings they appear to be approximately a meter above ground. It is unknown if the specific dimensions of the wall were pre-agreed in Brussels separate from the mock-up plan.