The ‘Joint History Project’ is an attempt to provide educators with a multi-perspective textbook on Balkan history, but its presentation of events in Kosovo omits key incidents, while many that are reported are presented superficially, inaccurately or with a pro-Serbian bias.

The founders of the Thessaloniki-based NGO Center for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeast Europe (CDRSEE) concluded that long-term reconciliation in the Balkans was possible only if there was a change in the way history was taught.

To this end, in 1999 they launched their most important project, the Joint History Project, in order to provide history teachers in the Balkans with various perspectives on the same event. The project was not only aimed at revising the ethnocentric lessons of history, but also at promoting critical thinking and debate, promoting diversity and accepting both the suffering and the shared achievements of the Balkan peoples.

CDRSEE engaged historians from throughout the region, and the project resulted in the compilation of six volumes, starting with the medieval history of the Balkans and taking it up to the present day.

During the creation of the textbooks, CDRSEE maintained a close working relationship with all of the education ministries in the region and received support from a total of 25 international donors. The six volumes were translated from the original English into 11 Balkan languages and promoted in many of the region’s capitals, including Prishtina.

The publication of the books was made possible with support from the EU, although the content itself remains “the sole responsibility of the authors and cannot in any way reflect the views of the EU.” However, it is also noteworthy that the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, has stated that she believed this project would contribute to overcoming the painful legacy of the past, and help younger generations in the region to understand the importance of moving forward together towards the EU.

This article will concentrate only on the sixth volume of this project, titled “Wars, Divisions, Integration (1990-2008)”, which was published in 2016 and is also available online. Our focus will be on how Kosovo’s recent history is presented in the book, which in part covers the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

The first chapter of the book, “Collapse and Construction 1990-1992”, is divided into four subchapters; Kosovo is included only in the third subchapter, entitled “Proclamations of Independence.” Here, the Constitutional Declaration on the Republic of Kosovo within Yugoslavia that was adopted by the Assembly of Kosovo on July 2, 1990, together with its integral text, is presented in a correct manner, albeit briefly.

Towards the end of the introduction to the second chapter, “The Disintegration of Yugoslavia”, there is a brief mention of the fact that Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in February 2008. Nowhere in the whole volume is there anything stated on the declaration of independence, nor the 2010 decision of the International Court of Justice relating to it.

The second chapter’s first subchapter, “The Path to Disintegration”, also gives a very superficial account of the Serbian repression of Kosovo Albanians in the early 1990s, focusing mainly on the expulsion of Albanians from their jobs, with a brief mention of an “increase in police violence and discrimination in schools.” Meanwhile, the presentation of Kosovo’s “parallel system”, which operated during the 1990s in a variety of areas, focuses only on the field of education.

Subchapters two, three and four of this chapter address the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the fifth subchapter, “The Wars of 1998-2001”, is almost entirely devoted to the Kosovo war.

The text states that after the creation of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), clashes began to mount, which, together with pressure from the international community, brought about the Rambouillet negotiations in France. Nowhere is there a mention of the fact that one of the main factors that triggered the armed clashes, and then the international community’s pressure in the Rambouillet negotiations, were the crimes of the Serbian and Yugoslav police and military forces against innocent Albanian civilians.

It is further stated in this subchapter that the KLA attacks resulted in mass emigration of the Serb population, which then led to the reinforcement of the Serbian and Yugoslav police and military forces, and that Serb paramilitary units began operating in Kosovo, leading to the Albanian population fleeing or being expelled en masse. The way the text is constructed, the implication is that paramilitary Serbian units were responsible for the deportation of Albanians, and not the Serbian and Yugoslav police and military forces.

It is also stated that the NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, FRY, was undertaken as “Serbian security forces were allegedly carrying out ethnic cleansing of Kosovo Albanians.” This was not an allegation, since even at the time there was documented evidence that the Yugoslav and Serbian police and military forces were committing purges, murders, rape, destruction, and so on.

Moreover, there is detailed mention of the material damage caused by the NATO bombing, but there is absolutely nothing on the material damage caused by the Serbian and Yugoslav police and military forces. Equally, there is nothing on rapes committed in Kosovo.

This period of war is illustrated in this subchapter with a total of three photographs, one showing five or six tractors loaded with Albanian refugees, and the other two showing damage from the NATO bombings in Serbia.

The Recak massacre of 15 January 1999, which saw 45 killed, is the only massacre in Kosovo presented in this volume, but under the title “The Racak Case”. The introductory text of this chapter states that “opinions about the incident are completely contrary,” as various international institutions consider it a massacre, while the Yugoslav authorities have claimed that all those killed were members of the KLA.

Starting from this premise, all of the massacres perpetrated by the Serbian and Yugoslav forces are controversial, because the Serbian and Yugoslav authorities have denied that any massacre was ever committed in Kosovo.

The textbook does not cover any other massacres committed in Kosovo, not even the Meja Massacre, where 376 innocent Kosovo Albanian civilians were killed, or the Krusha e Madhe Massacre, where more than 240 innocent Kosovo Albanian civilians were killed. The names of the village of Recak and other Kosovar villages and cities also appear in their Serbian forms throughout the book.

The sixth subchapter, “Atrocities and ethnic cleansing” has only one sentence on Kosovo, citing data from the Humanitarian Law Center that 13,421 people were killed during the conflict in Kosovo between January 1998 and December 2000, of which 10,533 were Albanians; 2,238 were Serbs; 126 were Roma and 100 were Bosniaks or from another ethnic group. It fails to state however which formations committed these killings.

In the seventh subchapter “Forced Migration and Refugees”, it is stated that “it is believed that 862,979 Albanians in total, or over 80% of the population as a whole, were expelled from Kosovo during the NATO bombing.” Why should something like this only be “believed” after such a precise figure of those expelled is given, not to mention the fact that this data was obtained from the UNHCR?

By comparison, when it comes to the departure of Serbs, the wording is: “according to official UNHCR figures, over 100,000 Serbs have left Kosovo after the Serbian police and Yugoslav army withdrew.” Also, why was it not specified in this subchapter who exactly expelled the numerous refugees created by the Kosovo war?

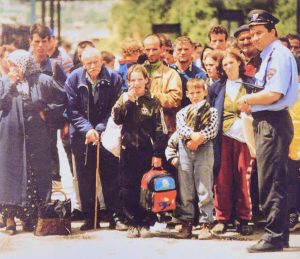

This subchapter is illustrated with two photographs of Albanian refugees in Macedonia. One shows about 20 refugees from Kosovo, accompanied by a policeman who seems very friendly to them. Meanwhile, the picture illustrating the expulsion of Serbs from Croatia during Operation Storm in 1995 is far more representative, not only in size, but especially in content, as it shows the long column of thousands of Serb refugees fleeing Croatia with tractors and trucks.

The eighth subchapter, “Children and Young People During the War”, provides only a short briefing dated March 22, 1999 on the interruption of teaching in Kosovo schools and the reduction of lectures and exams at the University of Prishtina. Since the subchapter is dedicated to children and young people, there should at least be a mention of the figure provided by the Humanitarian Law Center of 1,133 children that were killed or are still missing from the 1998-1999 war in Kosovo.

The ninth subchapter “Destroying Cultural Heritage”, contains a map presenting the destruction of 39 Serbian Orthodox churches after the war in Kosovo, without mentioning that the same churches and monasteries were subsequently rebuilt by the taxes of the citizens of Kosovo. While there is a brief mention of the more than 200 mosques and large number of traditional Albanian houses destroyed by the Serbian army in the introduction to the subchapter, there is no further elucidation on the figure, and is not stated that these were rebuilt through the help of various international humanitarian organizations.

The tenth subchapter, “Against the War” presents the calls, letters, petitions, strikes and protests by various Yugoslav personalities and organizations against the wars in Yugoslavia. The chapter contains no call, letter, petition, strike or protest of any person or organization from Kosovo against the war in Kosovo, although there were many at the time.

Chapter three, “International Actors, Local Issues,” contains a subchapter on international military intervention that also talks about peace negotiations and agreements. It presents two of the most important documents from 1999 in relation to Kosovo: the Rambouillet Agreement and UN Resolution 1244.

Concerning the Rambouillet Agreement, the only excerpts of this Agreement in this chapter are three of its articles on the immunity, rights and privileges of NATO’s military presence throughout the territory of the FRY. All three of these articles were used by Serbian official policy at the time to oppose the signing of the Rambouillet Agreement.

A similar approach is seemingly applied to Resolution 1244, as the moments which the authors of this book dwell on are the same as those repeated today by official Serbian policy: “Resolution 1244 guarantees the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the FRY over Kosovo”; “Resolution 1244 provides for broad autonomy for Kosovo under the FRY”; “Resolution 1244 enables a number of Serbian security forces to return to Kosovo.”

Moreover, when presenting this resolution, the authors of this book refer to Kosovo under the Serbian designation ‘Kosovo and Metohija’, which was made official by Slobodan Milosevic’s regime. It is especially the use of this designation that reinforces the impression that the chapters on Kosovo in this volume were written by historians indoctrinated by Serbian nationalism.

The third chapter also contains a subchapter on “Persecution, Courts and Tribunals,” which lists a table with the names of all convicts and acquittals from the Hague Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. In relation to Kosovo, only the indictment for crimes against humanity against the President of the FRY Slobodan Milosevic is mentioned.

Nowhere is it mentioned that in February 2009 and in January 2014 the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia convicted the following persons for war crimes in Kosovo: Nikola Sainovic, Deputy Prime Minister of Yugoslavia (22 years in prison), Dragoljub Ojdanic, Chief of the General Staff of the Yugoslav Army (15 years in prison), Nebojsa Pavkovic, Commander of the Third Battalion of the Yugoslav Army (22 years in prison), Vladimir Lazarevic, Commander of the Prishtina Corps of the Yugoslav Army (14 years in prison), Sreten Lukic, Commander of Serbian Police in Kosovo (20 years in prison).

Likewise, it should not be overlooked that the same tribunal, after the war crimes trials against Serbs in Kosovo, released KLA commanders Ramush Haradinaj, Fatmir Limaj, Idriz Balaj and Lahi Ibrahimaj and sentenced soldier Haradin Balaj.

In the fourth chapter “Economy and Society,” none of the five subchapters mentions Kosovo. However, Kosovo could be included in each of the subchapters, especially those entitled “Demography and migration”, which could have made mention of the numerous migrations of Kosovo Albanians during the 1990s, and the subchapter “Privatization and De-industrialization”, which could have included a section on the savage privatization in post-war Kosovo.

The same neglect of Kosovo continues in Chapter Five, entitled “Culture”, which is made up of three subchapters. The only exception here is the first subchapter “New Technologies and Communication”, where there is a short but exact mention of the use of satellite antennas in Kosovo between 1992 and 1999. The second subchapter “Religion” and the third “Cinema, Theater and Music” contain absolutely nothing on Kosovo.

The sixth and final chapter, “Ways of Remembering”, features a subchapter on the 1990s wars in Yugoslavia, entitled “Remembering the Last Wars.” All that is presented in this subchapter on the war in Kosovo are two monuments dedicated to NATO military intervention, both erected in Belgrade.

The first monument is dedicated to the bombing of the Serbian state-run television channel RTS, which features the names of the 16 killed RTS employees and a photograph of the bombed building. The second monument is dedicated to the 79 children killed by NATO attacks, centered on the sculpture of 3-year-old girl Milica Rakic.

This subchapter is not illustrated by any monuments erected to commemorate Albanians killed by Serb forces in Kosovo, nor the Serbs killed by KLA members, but focuses solely on the Serbs killed by NATO, without a text explaining that they were victims of collateral damage.

The authors of this publication should at least quote from a report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) entitled “Killing civilians during NATO air campaign”, which says that during the bombing campaign against the FRY, NATO killed 528 innocent civilians, including 318 Albanians killed in Kosovo.

The editors of this volume are university professors Christina Koulouri from Athens and Božo Repe from Ljubljana, while among its many committees, Kosovo is represented by a single member of the Resource Committee, Dr. Frasher Demaj from the Institute of History in Prishtina.

Being a member of the academy, Demaj claims in his biography published on the official website of the Kosovo Academy of Sciences and Arts that he is the author of several chapters in this publication. He was also among the panelists on the occasion of promoting this CDRSEE project in Prishtina.

This is quite surprising, given that Frasher Demaj is the author of many history textbooks for Kosovo’s primary and secondary schools, which contain inaccuracies and nationalistic exaggerations.

In this CDRSEE book, meanwhile, many of the most important events in Kosovo’s recent history (1990-2008) do not appear at all. On the other hand, many of the events in this publication appear superficially, incorrectly, inaccurately, are biased, and most of the time give the impression that the parts on Kosovo were drafted by historians indoctrinated by Serbian nationalism.

It should be added that the way the new history of Kosovo is presented in this publication does not at all contribute to CDRSEE’s alleged mission of overcoming the painful legacy of the past and the long-term reconciliation between the peoples of the Balkans and it must urgently change the way in which it presents Kosovo’s recent history.

The opinions expressed in the opinion section are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN.