Four photographers who showcased their work from the 1990s at BIRN’s Reporting House explain how difficult it was to document the hardships Kosovo faced until its liberation in 1999.

Four wartime photographers recall the hardships of documenting daily life in Kosovo in the 1990s and the importance of remembrance .

Their accounts, partially showcased in the ‘Reporting House’ exhibition, reveal the dedication required to ensure that the world witnessed the resistance and struggle of the Kosovar people.

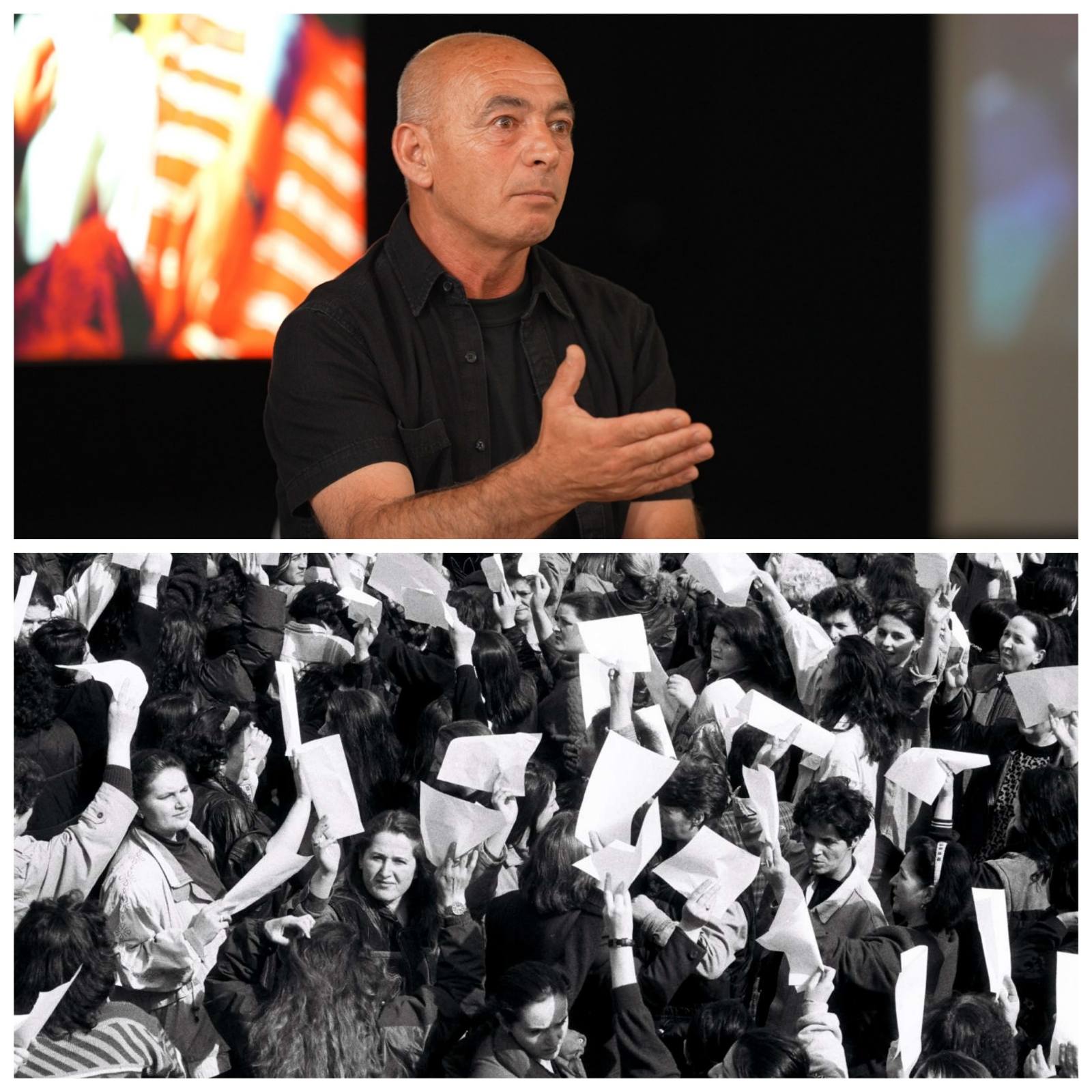

Photographer Ridvan Slivova began his career at the newspaper “Rilindja” at the age of 27. He worked as a photojournalist during the war in Kosovo from 1998-1999. In the show “Kallxo Përnime,” he recounted documenting the protests in 1998, which were organised by women in solidarity with the victims of killings and massacres in the Drenica region.

“There were also earlier protests organised by women. I took all these photos on film. This bread protest happened on March 16, 1998, after the killing of the Jashari Family. All of Drenica was blocked, and protests began to send bread there. The protest was stopped at the entrance to Fushë Kosova/Kosovo Polje, and we turned back. All this bread was later returned in front of the Red Cross building,” Slivova detailed.

Photographer Eliza Hoxha, who now is an MP in the opposition with the Democratic Party of Kosovo, PDK, explained how she took all of the film of the photographs she had taken during those years with her when she was a refugee in North Macedonia.

“They evicted us from the apartments on April 1, 1999. My mother insisted I shouldn’t take them (her films) in case it caused us problems,” she added, noting it took her 18 years to look at what was on those photo films she had taken.

“I hadn’t touched them since taking them to North Macedonia. The films were in the basement of the apartment since I had brought them from Macedonia. I worked on other projects such as those for the missing persons and at one point, when I decided I needed to see what I had, I realised I needed to digitise them to prevent further damage,” Hoxha continued.

Protests in Kosovo, in the period January – March, 1998, Prishtina. Photo: Courtesy of Ridvan Slivova

Hoxha also recalled a venue in Prishtina which was used for gatherings and discussions, from political to cultural, as Albanians in the 90s were forced to live a parallel life, excluded from the public system and official spaces.

“‘Hani i dy Robertëve’ was an alternative gallery. It was a café, restaurant, and gallery at the same time, it was where all the diplomacy was done. The gallery was in a basement, while the café was upstairs,” she said.

She added that, in a conversation years ago with a friend, it was noted that this café hadn’t received the attention it deserved, which led her to open an exhibition in 2017.

“We discussed how we hadn’t given that place the attention it deserves, the house of collective memory, for everything that happened there, both politically and historically and artistically. I told him I was only now returning to the films from the 90s, and he suggested I make an exhibition in 2017 called ‘Give Peace a Chance,'” she elaborated.

According to her, the exhibition was based on the idea that, as citizens, she and others could also contribute something.

“If I documented what was happening in the city with a camera back then, I could now bring back the energy of our social solidarity and mobilization, drawing attention to apartheid, human and cultural genocide that was happening here,” Hoxha added.

‘Bread for Drenica’ protest march in Pristina on March 16, 1998. Photo: Courtesy of Eliza Hoxha

Similarly, photographer Visar Kryeziu recounted how he was engaged with the BBC team and was able to document the daily fighting across Kosovo.

“In those conditions at that time, the cost of buying a camera was very high, as was buying film, developing film, and I worked as a waiter. At ‘Koha Ditore,’ I saw a job posting for a photojournalist, applied, and got the job,” Kryeziu said.

He further added that the war in Kosovo began only three months after he started working.

“I was quickly engaged by the BBC. David Loyn even said, ‘Our joy was when we found local translators, but we didn’t realise how happy they were to find us to work for their cause,'” Kryeziu remembered.

Kryeziu recalled how international media received their information first in Belgrade and then came only for a few pictures in Prishtina. This dynamic was frustrating for him, as everything about the Kosovo Albanian cause was interpreted through the framework of Serbian propaganda.

Photographer Visar Kryeziu. Photo: BIRN

“Some emissaries came to Prishtina and said that the KLA was a terrorist group. We were so indignant, knowing who they were. We took it as our mission to change that narrative, that perception. From Belgrade, they came with a ready-made story, identifying Kosovo Albanians with mosques and the traditional white cap,” he continued.

According to him, working with the BBC allowed him to avoid having his movement hindered by the Serbian police. “Going out with a ‘Koha Ditore’ team was impossible,” Kryeziu further recounted.

Meanwhile, Besnik Mehmeti, a photojournalist from North Macedonia, shared that he came to Kosovo in the 1990s to document the lives of ordinary citizens as well as the lives of KLA soldiers, who at the time were reluctant to appear publicly.

“I photographed the state of affairs, the lives of KLA soldiers, (and) ordinary life,” he said.

A Kosovo Albanian child during the war in 1999. Photo courtesy of Besnik Mehmeti

The four photojournalists emphasised that their similar approach to documenting the situation throughout the 1990s made the news from Kosovo credible, a significant challenge considering the powerful political machine in Belgrade.’