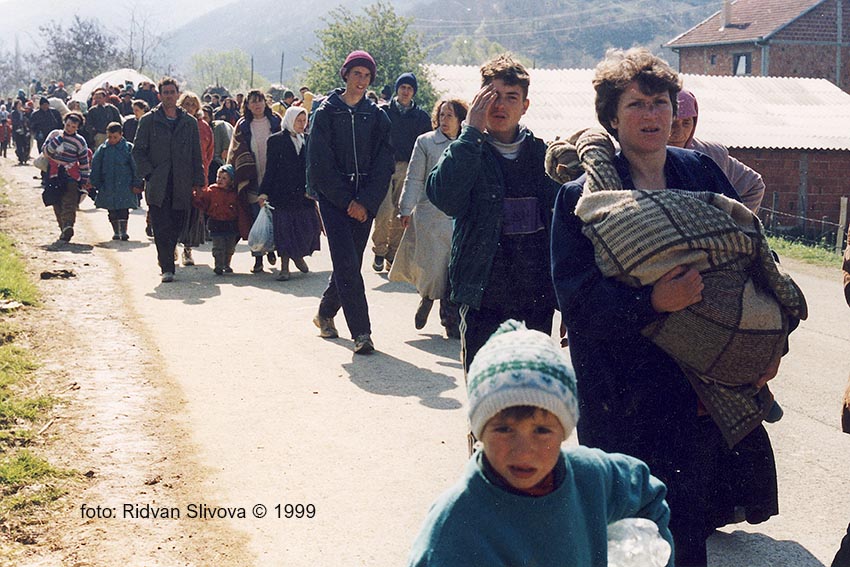

War photographer Ridvan Slivova revisits a picture he took in 1999 in the Kosovo mountains showing a mother and child attempting to maintain normality in desperate circumstances.

Many thousands of Kosovo Albanians fled their homes to avoid attacks by Milosevic’s forces around this time and ended up seeking refuge in remote villages. In one of these villages in the Gollak region of north-east Kosovo, Slivova captured a mother cutting her son’s hair as the boy knelt on the ground in front of her.

The mother’s face is gloomy and her grim expression reflects the fear she is feeling. A less-than-half-full bottle of water stands beside her to wash the child’s head.

“The photo was maybe taken on April 9, 1999, when I was displaced myself,” Slivova told BIRN in an interview in Pristina.

On March 24, a few hours before NATO launched its air strikes, as the security situation in Pristina deteriorated, Slivova had decided to leave home and go to his uncle’s place in the village of Makovc/Makovac, ten kilometres north of Pristina, in search of safety. “I did not even take a camera with me,” he said.

His younger brother took the risk of returning to see relatives who had remained in the city, and brought back a camera – but there were only six unexposed frames left on the film.

“When I got the camera in my hands, I started to visit the surrounding villages. Almost every day I visited a village and took photos of displaced people. There were thousands who were displaced from villages around Pristina and Podujeve but I didn’t have enough frames so I had to be careful how I used them,” he said.

‘I never thought the photo would survive’

In his photographs from the war, Slivova portrayed the bitter tragedy that befell many Kosovo Albanian families during 1998-99, but also their human efforts to survive and adapt to wartime conditions.

As part of their daily lives as displaced people in the fields or forests of Kosovo, mothers had to do things they had never done before, like cutting their children’s hair.

During the war, Slivova said that he was forced to go everywhere on foot as he sought to avoid Serbian troops, who were waging a violent campaign against the guerrillas of the Kosovo Liberation Army.

“I walked for more than three hours to go to this village,” he said.

In the area, he saw people who were spending nights under the open sky and preparing food outside as the village houses were full of displaced people.

“What I wanted to capture with this photo is beyond the presentation of the reality of life for displaced civilian people, despite the suffering they have faced, people struggled to maintain cleanliness,” he said.

“Besides the haircut activity that’s in focus, there are some clothes being dried in the background,” he added.

The photo was taken in circumstances of war, and Slivova said he was aware that it might never be developed.

It remained a negative for months and for several weeks it was even buried in a courtyard.

“I never imagined the photo would survive. I wasn’t certain I would survive either,” he said.

“I buried the negatives and told my relatives about the location. I wanted them to know in case I could not make it through the war. I wanted the photos to be a witness to the truth about what happened in this area,” he explained.

The negatives stayed buried until June 12, 1999, the day when NATO peacekeepers entered Kosovo after 78 days of air strikes by the Western military alliance which forced the withdrawal of Yugoslav forces from Kosovo.

A few days later, Slivova developed the pictures in Pristina. “The moment I had the photos in my hands, it was very emotional. A mixture of joy and sorrow for what we experienced,” he recalled.

‘Having a camera was dangerous’

“I have always felt this job to be a mission, not a profession,” said Slivova, now 54.

His career as photographer started in the late 1980s as a student, before he got a job with Rilindja, the only daily newspaper in Kosovo at that time, which ceased to be printed in August 1990 when the Serbian regime put it under its administration and fired all its ethnic Albanian staff.

Slivova said he got used to risk during the years of repression before the war.

“From 1989 onwards I was arrested many times by Serbian police, around 20 times. But during the war, having a camera was equal to having a weapon in your possession. Even more dangerous,” he said.

Since the war ended in 1999, Kosovo has not yet managed to create a proper archive of material documenting crimes committed during the conflict and the pre-war resistance to Serbian rule.

“I have photos of the arrests Serbian police made in 1990. They are living proof of what we have gone through,” Slivova said.

He recalled how, after the war, he offered his work to the Museum of Kosovo, but was told that they only wanted printed pictures, not negatives. “I have thousands of undeveloped photos, it costs too much for me to develop them,” he explained.

He said that every time he meets people who appear in his wartime photographs, it’s an emotional experience. “Sometimes I give them photos to keep as a memory,” he said.

“But I have never met the protagonists of this photo [of the boy and his mother]. I want to meet them and see how they look 23 years on.”