Yes. But with Kosovo’s lack of investment into its department for citizenship, asylum, and migration, be prepared for headache and possible citizenship-based discrimination.

I’ve heard something along these lines at least a handful of times over the past year: “In Kosovo, it’s easier to live illegally than it is to register.”

Of course, most countries have bureaucratic and complicated registration processes for foreign citizens hoping to live and work in their systems—legal processes that are often marked by inequalities and discrimination. In Kosovo, even people with deep roots to the country who want to claim their right to citizenship or residency may face barriers when it comes to attaining state documents.

Meanwhile, many foreign residents do not register their stays, whether due to misunderstandings of the law, disinterest in the complicated process, and for some, a general feeling that due to western-national privilege, threats associated with illegal migration will not extend to them. And for many unregistered foreigners who have lived in Kosovo since the Law on Foreigners was adopted in 2013, this has in fact been the case.

The Law on Foreigners foresees that foreigners (who enter without the need for a visa) may stay in Kosovo for a total of three months within a six month period.

There is a common misconception among foreigners that when you leave the country for, say, a weekend trip in Skopje, your three-month allowances starts over when you reenter Kosovo. Not so. An entry into Kosovo is considered illegal if the person has already used this three-month allowance within a six month period; only after six months from the first entry date does a person’s three-month allowance begin again.

Illustration: Jeta Dobranja/Trembelat for PI.

Not everyone has to register. Many internationals in Prishtina are protected under ‘diplomatic immunity,’ a privilege that also extends to spouses. Unfortunately, there is not a list available online to check which organizations fall under this immunity, but according to Valon Krasniqi, director of the Department for Citizenship, Asylum and Migration, DCAM, it includes missions such as KFOR, the EU Office, USAID, and EULEX.

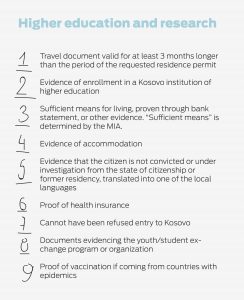

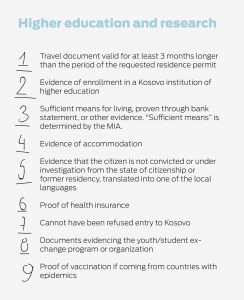

There are other categories of people who must register that are clearly outlined by the law, such as employees in local NGOs, freelancers, subcontractors (i.e. people involved in the construction of embassies), students, and researchers (even those on embassy-funded exchange programs).

*Note: These infographics should only be used as a guideline; please refer to the full list of requirements on the MFA website, which also includes other categories such as volunteer work, self-employment, and family reunification.

Foreigners apply for residence at DCAM, which is located in Prishtina and operated under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, MIA.

In 2016 I registered as a local employee, and the process was frustrating and confusing, but doable. I registered for an employment-based permit (other options include family reunification, secondary and higher education, scientific research, and humanitarian grounds, which includes refugees and victims of trafficking). I brought the required documents: my work contract, passport, a bank statement, a Kosovo-administered paper declaring my address where I lived with my partner, and a paper “evidencing that the citizen is not convicted… [or] under investigation by the state.”

Since this was first time registering, this last document had to be obtained from my home country. A friend of mine had gone through the process of obtaining a federal police report, another friend had simply printed a nondescript, one-sentence page from a free online background check. I chose something in the middle and had my father scan a paper from my local county court saying I had no open cases. Despite not being an original copy, it was accepted.

*Note: These infographics should only be used as a guideline; please refer to the full list of requirements on the MFA website, which also includes other categories such as volunteer work, self-employment, and family reunification.

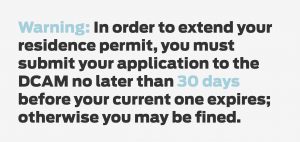

It took several weeks and I certainly faced some attitude from employees of the department, but that’s bureaucracy. But the somewhat frustrating process the first time around became a dysfunctional institutional mess when I re-registered a year later (by the way, here’s a small detail in the law that is important to know: in order to extend your residence permit, you must submit your application to the DCAM no later than 30 days before your current one expires. Some nationals I spoke to were fined for failing to comply). For each of my several trips to the office, lines were out of the door of foreign citizens young and old, most bringing an Albanian-speaker to help them through the process.

I won’t bore you with the details of my own experience, but I will say that after visiting the DCAM several times and countless hours in line with others, be prepared for possible bumps in the process. This may be due to your own misunderstanding of the paperwork required, or dysfunction within the office, which is only open from 9:00 to 3:00 (excluding a one-hour lunch break at 12:00).

Your experience may be shaped by your nationality or ethnicity. For example, a Turkish student in Prizren that I spoke to, who had travelled to Prishtina to pick up her permit, left in tears after standing in line for hours, feeling berated and disrespected by the staff when telling them she had forgotten her passport; American friends with me on that same day were not even asked.

Another friend of mine brought up the issue of family reunification for foreigners. A foreigner must legally reside in Kosovo for at least two years before they are eligible to bring family members to reside in Kosovo, including spouses. Look: For nationals who do not need a visa to enter the country, we probably all know someone working in Kosovo who has brought their spouse to live with them despite not fulfilling this two-year residency minimum. An American friend of mine, on the other hand, wanted to register her husband and the father of her small child—a Pakistani citizen and US green card holder—but was flat out told it would be impossible and is against Kosovo law. He was allowed to stay for the three months allotted to him by his pre-entry visa, and after that, had to leave Kosovo.

Illustration: Jeta Dobranja/Trembelat for PI.

There is also a major discrepancy in who gets reported if they fail to follow the law. According to data from the Kosovo Police, people who were deported in 2017 for failing to comply were nationals of the following countries: Albania (overwhelmingly), Columbia, Turkey, Bulgaria, the Philippines, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Armenia, and Serbia. Notice who is not on the list–probably a lot of our non-registered friends from countries like the US, the UK, and France.

Some choose not to register because they are confident that their national privilege will allow them to easily get away with going undocumented according to Kosovo law. But the government is failing to do its part as well, because services and communication are poorly organized.

For example, the Ministry of Interior is not even sure itself what to do with the many interns in the country who intern at missions under diplomatic immunity. In a response, the ministry said that it has never dealt with a request in this regard, but in their opinion, registration of interns in diplomatic and international missions should be required under Article 57 of the Law on Foreigners, which addresses internships and student exchange programs.

There was an increase in residency applications after media reported in late 2016 about Albanian citizens working in Kosovo being deported for failing to register. In 2017, according to the MIA, there were over 1,000 more applicants for residency than in 2016, though DCAM had the same staff, budget, and poor infrastructure (a small building that lacks seating, a ticketing system, and central heating). The building needs more funding and more staff with better sensitivity training, as it covers important services for returnees, asylum-seekers, citizenship services, and residency.

But while living in this world of borders, people with citizenship privilege need to treat Kosovo law like anywhere else we hope to live, work, and study. Plus, there is always a chance that you might face fines or worse.