Kosovo’s most turbulent decade returned to the screen as Youth Initiative for Human Rights premiered “Kosova 1989–1999” at Kino Armata, a documentary tracing the years from Milosevic’s rise to Kosovo’s liberation and declaration of independence.

On December 11, Kino Armata was packed full with an audience ready to revisit a defining chapter of Kosovo’s past. The premiere of “Kosova 1989–1999” was not just a documentary screening, but a collective act of remembering a decade that shaped a struggling nation.

The screening was followed by a conversation with Tim Judah, one of the world’s best-known chroniclers of the Balkans, and Veton Surroi, publicist, writer, and witness to the era. The conversation focused on the process of state-building—and on what still remains unfinished in Kosovo.

The film begins in 1987, with a scene that is now regarded as the opening act of intensifying unrest in Kosovo. In Fushë Kosovë, the emerging Serbian communist leader Slobodan Milosevic addressed a crowd of Kosovo Serbs, declaring, “No one is allowed to beat you.”

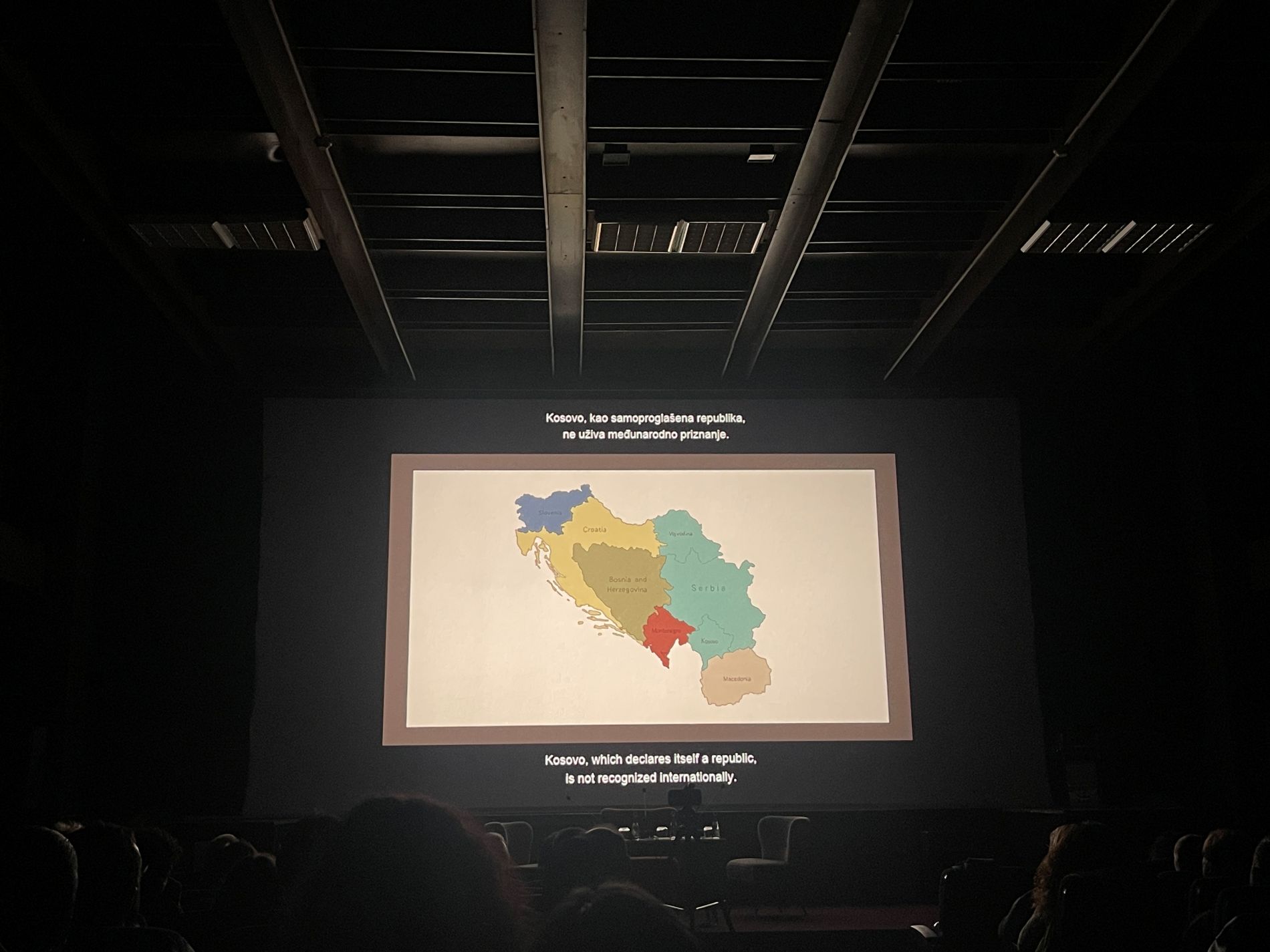

Within two years, Kosovo’s autonomy was dismantled. The documentary mentions mass demonstrations by Albanians, systematic arrests, and the tightening of Belgrade’s rule. It also explores Gazimestan in 1989, where the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo became another stage for Milosevic’s expansionist rhetoric.

Building a parallel state

The launch of the documentary “Kosova 1989–1999” at Kino Armata in Prishtina, December 11, 2025. Photo: BIRN

As institutions closed their doors to Albanians, Kosovo society constructed a parallel world. Schools and universities moved into private homes; doctors treated patients in improvised clinics; and a self-funded system—sustained by local taxes and diaspora contributions—kept an entire community functioning in the shadows.

The film revisits the formation of the LDK, the rise of Ibrahim Rugova, and the extraordinary blood-feud reconciliation movement, which brought communities together at a moment when unity was a political act of survival.

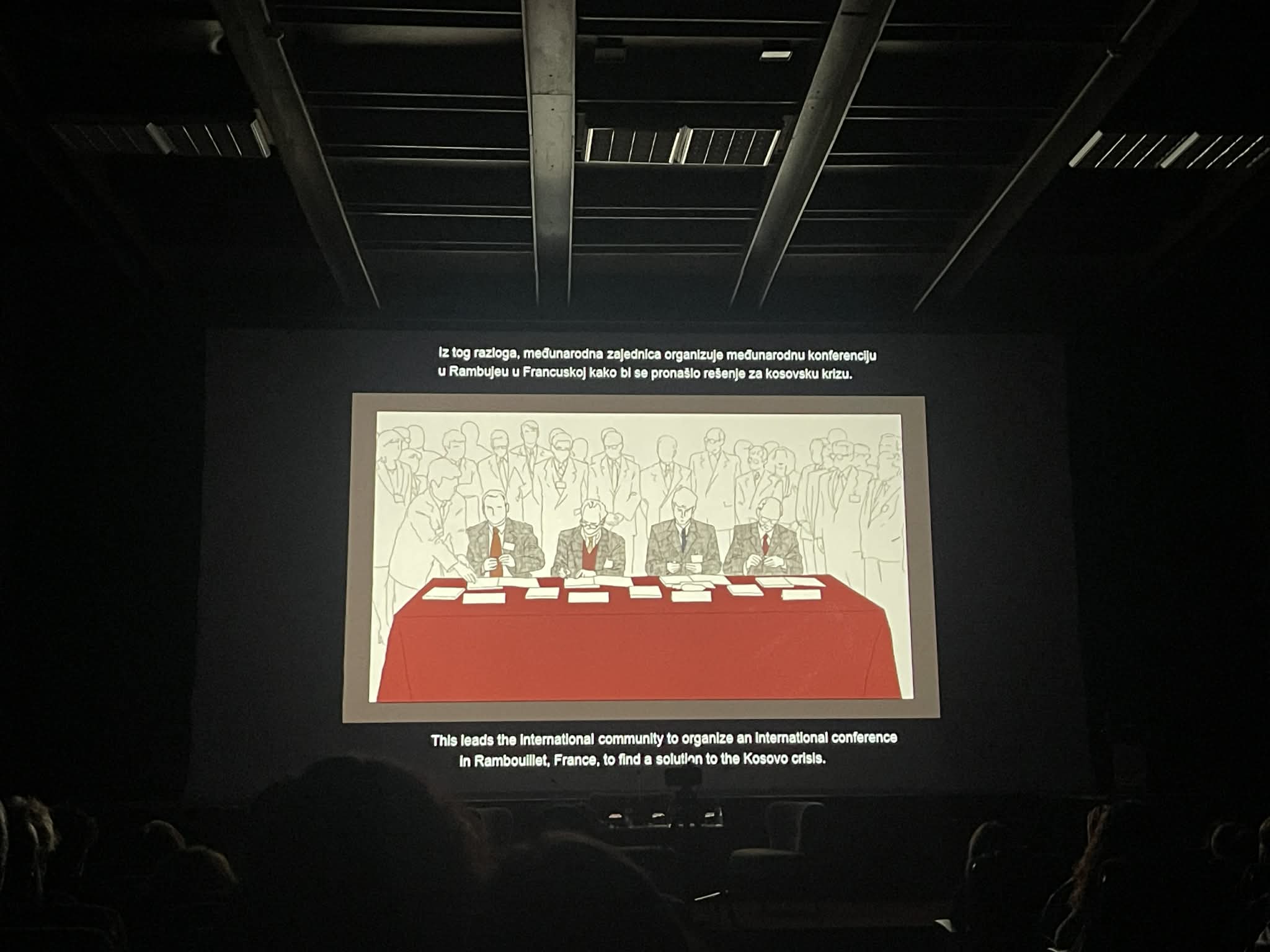

The mid-1990s saw a shift. The documentary traces the emergence of the KLA, whose first public appearance at a teacher’s funeral in Drenica signaled a new phase. Soon, the region became the epicenter of escalating violence: targeted killings, village raids, and ultimately the Recak massacre, which shocked the world and shattered the illusion that Kosovo’s suffering could remain invisible.

When Serbia refused to sign the Rambouillet Agreement, NATO launched its 78-day bombing campaign. Serbian forces intensified their attacks with killings, mass expulsions, and systematic sexual violence. More than 10,000 civilians were killed. In June 1999, NATO troops entered Kosovo, followed by the establishment of UNMIK.

Kosovo declared independence in 2008, and in 2010 the International Court of Justice affirmed that the declaration violated no principle of international law.

How Serbia manufactured Milosevic and how Kosovo resisted him

The launch of the documentary “Kosova 1989–1999” at Kino Armata in Prishtina, December 11, 2025. Photo: BIRN

During the post-screening discussion, Veton Surroi argued that Milosevic was not an accident but a product of wider nationalist machinery.

“Autocracy in Serbia produced Slobodan Milosevic,” he said. “The church, the media, and a university system steeped in nationalism created a cohesion that ultimately brought him to power.”

Kosovo’s answer, Surroi emphasised, was extraordinary:

“We built a peaceful resistance and a level of social cohesion unseen before. It was a dramatic turn toward the West at a moment when Serbia pursued a historically anachronistic project. That friction—peace against nationalism—is what brought us our freedom.”

Surroi described the Dayton Agreement as a turning point of disillusionment for Kosovo: “Dayton did not mention Kosovo. It was a collective shock. The answer was that to get attention, you had to draw it by force.”

He also highlighted the historic significance of U.S. policy: “In 1991, President Bush warned Serbia that if it took offensive action against Kosovo, the U.S. reserved the right to act unilaterally. That threat was fulfilled in 1999 through NATO. It was, in a sense, a reward for Kosovo’s peaceful resistance.”

When speaking of Europe, Surroi noted: “The EU has shown it lacks geopolitical weight. After more than 30 years of negotiations, it still cannot mediate a final settlement. To remain in this position would be shameful.”

Reporting a crisis the world initially ignored

The launch of the documentary “Kosova 1989–1999” at Kino Armata in Prishtina, December 11, 2025. Photo: BIRN

Tim Judah recalled the early 1990s as a strange and frustrating time for journalists.

“It was difficult to report from Kosovo because, oddly enough, not much was happening—at least visually. Kosovo was oppressed, it also was slightly surreal as you had Rugova driving around in his presidential Audi, there was elections, which the Serbs did not make much attempt to stop because thy did not want trouble here, they were fighting in Croatia and Bosnia.”

“Global media attention followed the images of war elsewhere. Kosovo simply could not compete—until 1997”, he further noted.

“When Albania collapsed in 1997, hundreds of thousands of weapons flooded the region,” Judah said. “Suddenly an armed uprising was possible. It completely changed the history.”

Unable to enter Kosovo during the NATO bombings as he needed a visa, Judah reported from Albania and North Macedonia.

“In many ways, what pushed NATO to act so quickly was Srebrenica. The West thought: ‘This is happening again. We have to intervene.’”

He reflected on Kosovo’s transformation: “Today the construction boom is astonishing. In the ’90s, Kosovo was deeply underdeveloped. But while much has changed, the region has not moved forward as fast as it could have. After the wars, the world simply forgot about it, until Ukraine put it back on the agenda.”

“I will try to paraphrase Lenin who said: ‘there are decades where nothing happens and then weeks when decades happen’,” describing what happened here in Kosovo.

Surroi warned that Kosovo and Serbia remain locked in a conflict that has not truly ended.

“We still live in a culture of war, not peace. After the [International Court of Justice] ICJ ruling in 2010, Kosovo made a mistake by entering negotiations where its statehood became contestable. We lost 15 years.”

“Peace is not impossible. We simply lack leaders who want it,” Tim Judah concluded.