The Second World War is taught in a subjective manner, Kosovo history teachers and scholars claim.

It is another early Monday morning at central Prishtina’s “Faik Konica” elementary school and students are running to make it to class on time. For ninth grade students that means 45 minutes of history class. They arrive bored, kind of hating the Monday, as it is fashionable nowadays to express hate for Mondays publicly.

“You don’t hate Mondays, you hate capitalism,” the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek would quip. But these children probably have no clue what capitalism is. This behavior of boredom on Mondays is just a mere imitation of adults, most probably their parents.

In contrast to the bored faces of the majority of the class, teacher Donika Xhemajli seems to be full of energy. And soon, the students too start to get energized by Xhemajli’s questions about the key moments of the Second World War.

History teacher Xhemajli and a student pantomiming. | Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

The ninth graders are surprisingly well-versed on the main ideological divisions between nationalist and communist Albanians who fought in the war. They know details about the divisions between the Balli Kombetar (the National Front) and the communists. They even know that the Ballists, who fought for Kosovo’s unification with Albania, did not trust Enver Hoxha (who would become the communist leader of Albania) because of his close ties to the Yugoslav Communist Party.

“A lot of kids know about the Ballists since their grandfathers used to be in the organization, so they have heard different stories,” says Xhemajli.

Until recently most of these stories were transmitted only orally, since they were not part of official Yugoslav historiography.

“I let them share what they know with us in class, what they were told by their families.” This “dialogue of narratives,” as she calls it, is important to her.

At this phase of the class, students learn about the main ideological and political divisions between local and regional groups and about the Axis powers and Allied forces.

When it comes to cooperation between Albanians and Serbs, Xhemajli explains that this topic is not covered in the lessons. She has to follow the curricula determined by the Ministry of Education and as such she feels like she cannot deviate too much from the lesson plans.

However, she says, she tries “to give them other perspectives that are missing in the textbooks.”

In her point of view, history textbooks are very “narrative,” meaning that authors blatantly insert their views into the texts. The textbooks selected by the ministry cannot be changed or replaced by schools or teachers.

“I have no choice, I have only one book, which I have to follow,” she says.

Still, Xhemajli is optimistic when it comes elaborating the content within the books. She thinks that it is up to teachers to increase the critical perspective over different issues portrayed in the textbooks.

“The whole issue centers on how teachers raise the questions,” says Xhemajli, who tries to raise questions about the topics discussed in class from different perspectives.

When asked, students say that they don’t remember cases when their history teachers brought up topics that are not in the books. But they confirm that the role of the teacher is crucial since for them the textbooks have a lot of unclear information. In some cases, they say, teachers provide information with more details that they think are important.

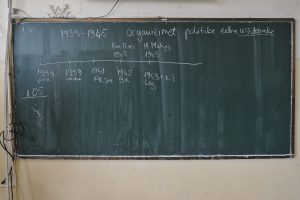

On the blackboard, major events of WWII. | Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

According to a recent report on Kosovo’s history textbooks, teachers “are also conformist, and largely conform to administrative directives such as curricula and programs, as long as they do not contradict deeply held beliefs that are rooted in personal and communal stories about the Second World War.”

The report, written by the Kosovo Oral History Initiative, was based on interviews conducted with teachers and authors of history textbooks from different ethnic backgrounds and regions in Kosovo.

“It was the birth of Yugoslavia; 1945 is the beginning of new Europe,” says report author Anna Di Lellio about the importance of the war.

However, she is concerned that the way this period of history is taught by teachers in Kosovo is problematic.

“Albanian and Serb teachers teach the history of WWII in ways that are not up to date with contemporary scholarship,” says Di Lellio, adding that teachers are also subjective.

“They teach [WWII history] with their traumatic relationship with that history, depending on their experience, their families’ experiences or their community’s experience,” says Di Lellio.

However, the problem is not only with individuals.

According to Shkelzen Gashi, author of a report on how regional history textbooks treat history, this subjectivity is a regional failing, not only amongst teachers but also in the history books themselves.

For example, Gashi explains that Kosovo’s textbooks ignore the cooperation that took place between Kosovo Albanian Communists and Tito’s Yugoslav Partisan Army – and the cooperation between Kosovo Albanian nationalists and the Fascist occupying forces.

When it comes to crimes committed by Albanians against Serbs, Kosovo’s history textbooks remain silent.

“Between 1941 and 1944, the crimes committed by Albanians are presented in Serbia’s history textbooks but not in Kosovo’s or Albania’s,” says Gashi.

“For Serbs, Kosovo Albanians are not even a factor. According to them, WWII in Kosovo was a genocide against Serbs by Albanians who collaborated with Italians and Germans,” affirms Di Lellio.

Both authors agree on the problematic language used in Kosovo and Serbian history teaching. Di Lellio explained how teachers in Gracanica, which is ten kilometers from Prishtina, refer Albanians as “Albanci,” while in Mitrovica, in the northern part of Kosovo, teachers refer to Albanians as “Siptari,” a derogatory term to distinguish between Albanians and Kosovo Albanians.

Elementary school Faik Konica in Prishtina. | Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

Di Lellio is convinced that the solution to this collective amnesia and use of derogatory words should not come from the teachers but from serious scholarship that must be developed by the academic community.

Kosovo’s Ministry of Education has initiated steps to reform primary school curricula by the end of 2017. As the reform is ongoing, debates between different interest groups continue.

In the meantime, a generation of elementary school students has already grown into adults. As this situation persists, they not only model their behavior on their role models — parents and teachers — but they also imitate the very approaches and ideas that sent this region to war many times.