As construction gets underway along Route 6, a highway connecting Prishtina to Macedonian border which traverses through agricultural land, farmers and economy experts fail to see the benefits of yet another costly highway.

BABUSHI I MUHAXHEREVE, Kosovo – Haki Qamili spends his days tending to his land, where chickens roam freely in the open yard. A drinking well sits at the edge of the yard, close to a spacious garage and a group of sheds where farming equipment and fresh stacks of hay are stored. His home is on the other side of the yard, across from a cluster of fruit trees. Qamili’s large grassy plot of land sits along a small dirt road in this quiet village. The most traffic that comes along here is a few cars and schoolchildren walking to and from their homes.

Soon, a stretch of Route 6 – Kosovo’s new national motorway from Prishtina to Hani i Elezit, on the border with Macedonia – will be passing through Qamili’s front yard, splitting his property into two pieces of land. It’s not something he and his family want to see happening, but as construction is already underway, there seems little Qamili can do to prevent his home from turning into a motorway.

“The construction of the road damaged me a lot already and it’s bad because they’re splitting the village in half,” Qamili, 74, said on a blustery February afternoon while working in his yard.

Enlarge

Qamili’s home has become a strategic spot on the road, which has a baseline cost of 599 million euro, which does not include the costs for expropriating property along the route. The highway is funded entirely by the Kosovo government and worth almost half of the country’s budget at the time of signing the contract in June 2014. It is being built by the global engineering and construction company Bechtel Corporation and joint-venture partner Enka, a Turkish construction company, on behalf of the Ministry of Infrastructure.

Bechtel is no stranger to road construction in this part of the Balkans, having already completed 28,000 km of roads in the region, including highways in Albania, Turkey, Croatia, as well as Kosovo’s first national highway, the 77- kilometer Route 7 to the Albanian border, for which Kosovo’s taxpayers shelled out a hefty 966 million euros.

Construction of the new road commenced in the summer of 2014 and it has finally reached Qamili’s doorstep. He and his family are now wondering what will happen to their home and livelihoods. Construction has halted for now – Qamili said he is suing the government for more money for his land: they valued his land for 3,500 euros per are (one are is equivalent to 100 meters squared). Qamili believes his land is worth more and is asking for 10,000 euros per are. Until that is resolved, he will continue farming his land without the threat of the construction of the road creeping towards his property.

“When they were here it was loud and dusty,” he said. From both sides of his fenced-in property, one can easily see where the construction has stopped and continued on the other side of his home: mounds of rocks serve as the foundation of the new road.

“In France or in Germany they wouldn’t have done this, they should have used the mountains to build the road,” Qamili said. He has spent time in France and still retains citizenship there and his sons reside in Germany. Despite the option to leave Kosovo, he wants to stay and protect his property.

Qamili is not alone.

Residents living along the 60 kilometer Route 6 are uncertain of how the presence of vehicles, including trucks, barreling through their villages will affect their daily lives. Many of them depend on the fertile agriculture land in this part of Kosovo to grow crops such as wheat and corn. Around 80 percent of the land affected by the construction of the new motorway is agricultural, according to the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning.

“There is nothing bad with having roads but it’s bad that they used our agricultural land. This is what live by, we do not work on anything else, we only have agriculture here,” said Nexhat Marevci, 48, a farmer who lives in the village of Marevc, a few kilometers away from Babush. His neighbors, also farmers, with whom he often takes afternoon walks along the village road, feel the same way.

Vast swaths of agriculture land dominate the landscape in Marevci’s village, which will be replaced with Route 6. According to Marevci, around 15 families are affected by the new highway and were forced to sell their land to make way for its construction.

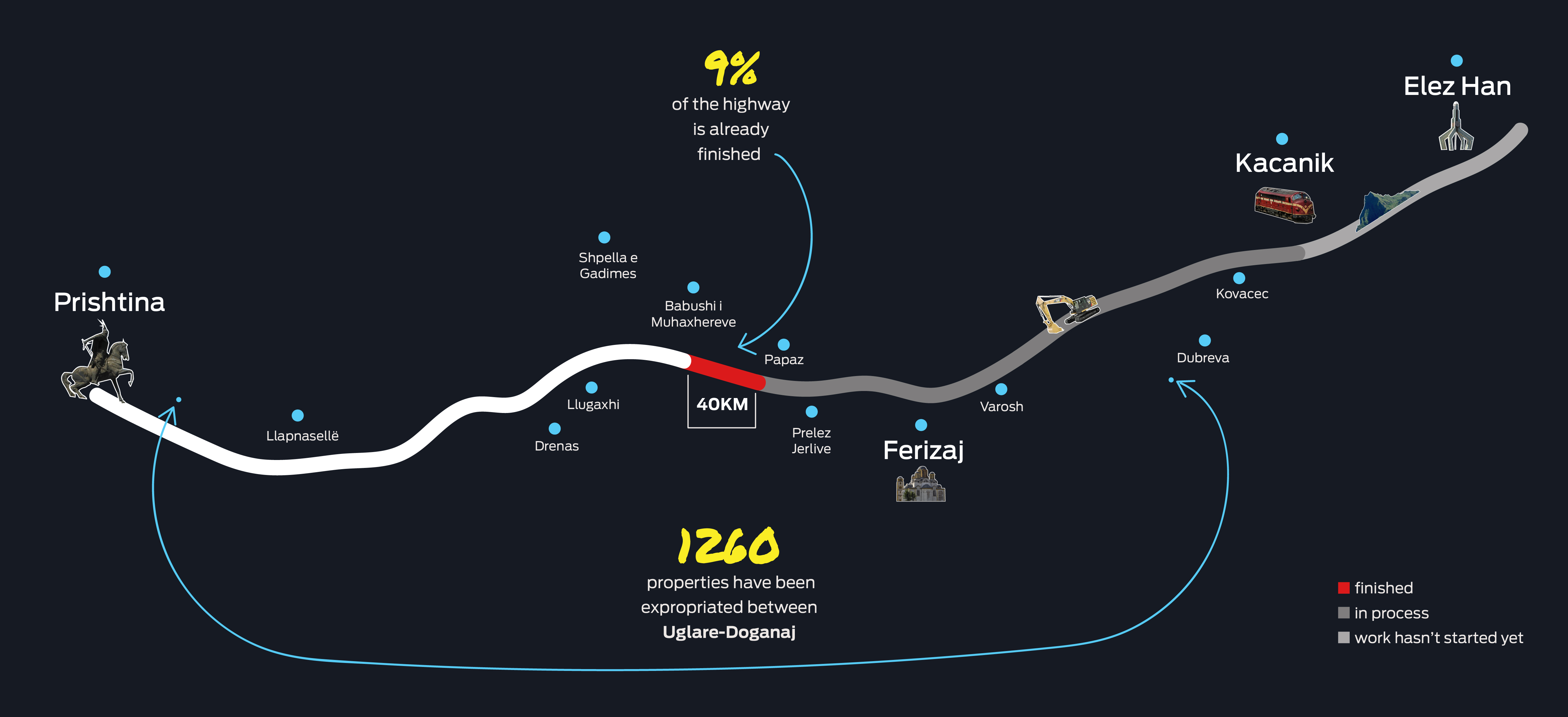

So far, 1,260 properties covering an area of 252 hectares – an approximate value of 64,181,544 euros – have been expropriated by the government. The total cost of land acquisition is yet to be determined, but already some landowners are receiving up to 40,000 euros for their properties. The Ministry of Infrastructure has requested that an additional 890 properties be expropriated in order for the construction of the motorway to advance towards the Kosovo-Macedonia border. Eleven families have had to vacate their homes thus far, according to the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning.

Marevci sees the benefit of what a modern motorway and infrastructure can bring to local businesses, but thinks it could have been built elsewhere.

“They could have used the existing road and not damaged the land so much. They also could have used the mountains up there and they would have had to do much less expropriation because the majority of the land there belongs to the state,” he said, pointing to the hills in the distance.

That would not have been feasible, says Rame Qupeva, Director of the Road Infrastructure Department at the Ministry of Infrastructure. He is directly overseeing the Route 6 project. The existing road from Prishtina to Hani i Elezit is the most congested road in Kosovo, according to Qupeva, and Route 6 will drastically transform all of this.

Bechtel/Enka construction workers build an overpass between the village of Babush and Cërnillë so that people from the villages surrounding Route 6 can have access to the new motorway. Photo: Valerie Plesch.

“It will change the transport network in Kosovo,” Qupeva said of the new route, especially transit time between Prishtina and the border with Macedonia, which currently takes about an hour and a half. Qupeva was also responsible for the Route 7 project.

Kosovo’s Route 6, also known as the Arber Xhaferi highway, named after the late Albanian politician from Macedonia, will pass through dozens of villages like Marevc and Babushi i Muhaxhereve as it makes its way from Prishtina to the border crossing town of Hani i Elezit, ending a few kilometers away from the entry point to Macedonia. It is supposed to become a vital passageway and transit route for goods coming from Greece’s port at Thessalonki, about 260 kilometers away and into Macedonia before entering Kosovo. This transit route is also part of Kosovo and the region’s southern trade route. According to research conducted by the RIINVEST, 35% of Kosovo’s trade exchange passes through Hani i Elezit, making it the busiest customs point.

“Kosovo – a landlocked country – will become a transit country and will be the shortest way to the Adriatic Coast and also to the eastern part connecting [existing corridors] with the rest of the region,” said Qupeva. “That’s why this road is not only for Kosovo but also is for the regional transport network.”

Alban Zogaj, an economic researcher from RIINVEST and the lead author of a 2015 report on Route 6, says that economic results from the controversial Route 7 project are still yet to be seen in Kosovo.

“Albania benefited from the road, mainly in tourism, but not Kosovar producers and the Kosovo tourism sector – not yet,” Zogaj said during an interview in Prishtina. It may take a few more years to see a financial gain from Route 7 on Kosovo’s economy, but at this point, there isn’t much hope.

“We will have a very good link with Macedonia and with other countries in the region, meaning Bulgaria and Serbia through [the new motorway]. The volume of trade will go up, for sure, but it will go up for the benefit of Macedonia and not for the benefit of our country,” Zogaj said.

Visible from Google Earth and from the current Prishtina-Skopje highway, known locally as M2- and considered Kosovo’s main artery – are signs that the massive road project is taking place throughout Kosovo’s countryside.

However, construction of Kosovo’s second motorway comes at time in the country’s economy when funding for public projects could have been invested elsewhere. It is not known where exactly the government had to cut in order to allocate the 599 million euros for Route 6 – this information has not been made available to the public – but Zogaj thinks it’s only logical it came from important projects in the education, health and agriculture sectors. Funding cuts for other public projects also suffered during implementation of the 2011-2013 Route 7 project, as highlighted in a 2014 story by Prishtina Insight.

More troublesome, not all of the funding for the Route 6 project was allocated by the government at the time of signing the contract in June 2014. “The money was not there,” says RIINVEST’s report. The research also concluded that at an average of 11.5 million euros per kilometer, Kosovo is ranked the second most expensive place to build a highway out of a group of nine European countries.

View of the Route 6 gravel base and the remaining agricultural land between Babush and Cërnillë. Photo: Valerie Plesch.

“They [high quality roads] are expensive for the current status of this economy. People don’t have cars to use that road, so why do you need it?” Zogaj said.

“Our argument was that we do not need these huge, very expensive and very luxurious roads, because the economy of Kosovo is small, we could have managed doing smaller roads with smaller amounts of investments that could have pretty much the same affect on the economy and use the rest of the funds for other investments that are very much needed in the economy.”

Kosovo’s first motorway, Route 7, built by the Bechtel/Enka consortium team, was wracked by scandals, including lack of transparency on the bidding process, above average market costs for construction materials and perhaps the most striking of all, the final result: a nearly empty highway.

In 2015 Foreign Policy reported that Route 7 is “used at less than one-third of its capacity, according to the government’s own traffic count and information provided by international economic experts.”

From the outskirts of Prishtina, villages are already seeing the changes in the landscapes. Endless clumps of large white and yellow rocks mark the construction trail of the new road as it cuts through the mostly empty fields in Lipjan and onto the other side of the M2 to the village of Babush. Already about two and a half million cubic meters of rocks sourced from local quarries have been placed and flattened over land as part of the foundation of the road. In other parts, like in Lipjan, they are now putting the finishing touches by covering them with asphalt.

Construction recently stopped in the village of Papaz, near Ferizaj, as the ruins of a church believed to be from the Roman era were found over the summer during excavation of the road. Another factor that has hindered operations is the process of expropriating land, which is approved by the Prime Minister’s office and administered by the Ministry of Environmental and Spatial Planning.

Qupeva remains adamant that his ministry does not want to destroy homes, but it is inevitable that residents’ way of life will be changed.

“Whenever you do a road project, the biggest problem is the houses, because the motorway cannot be like a snake,” Qupeva said. “We try to avoid destroying homes as much as possible, but at the end of day, we have to go through somewhere.”

With a maximum speed limit of 120km/hour, travel time from Prishtina to the border with Macedonia will take approximately 20 minutes. To Ferizaj, it will take just 15 minutes, down from an average commute time of 45 minutes.

Despite these changes in transportation in the small Balkan country, which will soon have a pair of modern motorways built to Trans-European North-South Motorway (TEM) standards, not everyone is satisfied at how things have been handled.

Enlarge

In Babush, Sali Sylejmani, 44, lives on a small road shared by two other homes that belong to his brothers. He moved there after the 1998-1999 war with Serbia and has since built a life for himself and his family. Now, he shares his backyard with debris from the road construction. He’s uncertain if he will be able to keep his cows and chickens once Route 6 is complete. He also worries about the safety of his children.

Sylejmani organized a petition against the construction of the road in the village. He received 600 signatures in less than two hours with the help of residents in his village and presented it to the municipality office in Lipjan. Nothing came out of it.

“I almost got a full salary from my milk sales. There are many families who are 100% dependent on the sale of milk,” Sylejmani said. As he was talking, a young boy living nearby bought two liters of fresh milk from Sylejmani’s family. “Look at the boy here who bought milk from us. After I get rid of my cows, he will have to buy the artificial milk at the store.”

Servet Meric Kursad, Enka’s Earthworks Manager for the Prishtina-Hani I Elezit Motorway Project from Turkey, spends his days inspecting the construction sites. He calls the design of the motorway “the most reliable design” and believes that it will “benefit all the Kosovo people.”

Kursad also worked on Route 7 and he and his colleagues brought many local workers from that project to work on Route 6. Many of them are Turkish speakers from Prizren, which makes it easier for them to work with the Enka employees.

Currently there are around 600 workers, including local subcontractors, according to Ela Ruci, Bechtel’s PR manager, and she expects that the number will ramp up when more land is expropriated. Work is based on the season, and though Bechtel/Enka said they trained 11,000 people for Route 7 – possibly making them one of the largest foreign employers in Kosovo – not all of the work was for a long period of time and it was spread out along different sections of the road. Zogaj doesn’t consider this type of employment as sustainable and beneficial to Kosovars. Unlike other international companies in Kosovo, such as Ferronikeli, which invests in the country, Bechtel/Enka will leave once the project is complete.

Currently there are around 600 workers, including local subcontractors, according to Ela Ruci, Bechtel’s PR manager, and she expects that the number will ramp up when more land is expropriated. Work is based on the season, and though Bechtel/Enka said they trained 11,000 people for Route 7 – possibly making them one of the largest foreign employers in Kosovo – not all of the work was for a long period of time and it was spread out along different sections of the road. Zogaj doesn’t consider this type of employment as sustainable and beneficial to Kosovars. Unlike other international companies in Kosovo, such as Ferronikeli, which invests in the country, Bechtel/Enka will leave once the project is complete.

Back in Babushi i Muhaxhereve, some locals are not happy that their homes now abut their country’s second national highway, and they believe the conditions will not improve after the construction.

Enlarge

Dairy farmer Shpejtim Azemi, 38, and his wife Antigona Azemi, 33, depend on a water well in their front yard to feed their family, cows and chickens. Like the Qamilis next door, Route 6 is designed to come through their yard.

“Our home will be too close to the highway for anyone to live in it. It will be somewhere from seven to eight meters in front of the house,” Shpejtim Azemi said.

“The highway will also destroy my business, because of the well here. If they destroy my well here then I will not have access to drinking water, and I won’t be able to have water for the cows or anyone anymore.”

Despite being paid around 22,000 euros last December by the government for Bechtel/Enka to use the land in front of his house for the highway part, he says he would gladly return that money if his land would be left untouched.

For many residents like the Azemis living along the construction route, they are already beginning to see a grim future once the road is complete.

“There will be no comfort here anymore, it’s done here,” Azemi said.