The Presevo valley and north Kosovo are not monoethnic spaces. Eventual territorial swaps would lead to an inevitable dislocation of populations.

As they were getting ready to celebrate the drawing of borders in Europe, an advisor approaches the table where the ambassadors of the Great Powers are seated, and reminds them that they have still not made a decision on the wild territory that is the Balkans. Disappointed to find that they have more work left, the ambassadors return to the table and look at the map they have laid out in front of them. They make a few lines here and there, exclaiming: “Here, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Kosovo and Great Serbia. Are you happy?”

“As you like,” the other ambassadors respond, after which they toast their glasses for achieving eternal peace in Europe.

Perhaps this is how it really happened 370 years ago, but this description comes straight out of a Fry and Laurie sketch, which satirizes the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 when, after the 30-year war on the continent of Europe, the winning parties ‘corrected’ the borders in the Balkans. Today, Kosovo President Hashim Thaci is the one who’s talking about correcting borders.

A taboo topic until recently, the possibility of redefining borders in the Balkans, starting with changing the borders between Kosovo and Serbia, has been discussed loudly in the past few weeks. On one hand, President Thaci is continuously claiming that correcting borders does not imply the separation of the north of Kosovo, but does mean that the Presevo Valley would join Kosovo. On the other hand, Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic sees ‘the correction’ a bit differently. For him and other politicians in Serbia, correction of borders does not imply the partition of Presevo Valley from Serbia, but it means that north Kosovo would join Serbia.

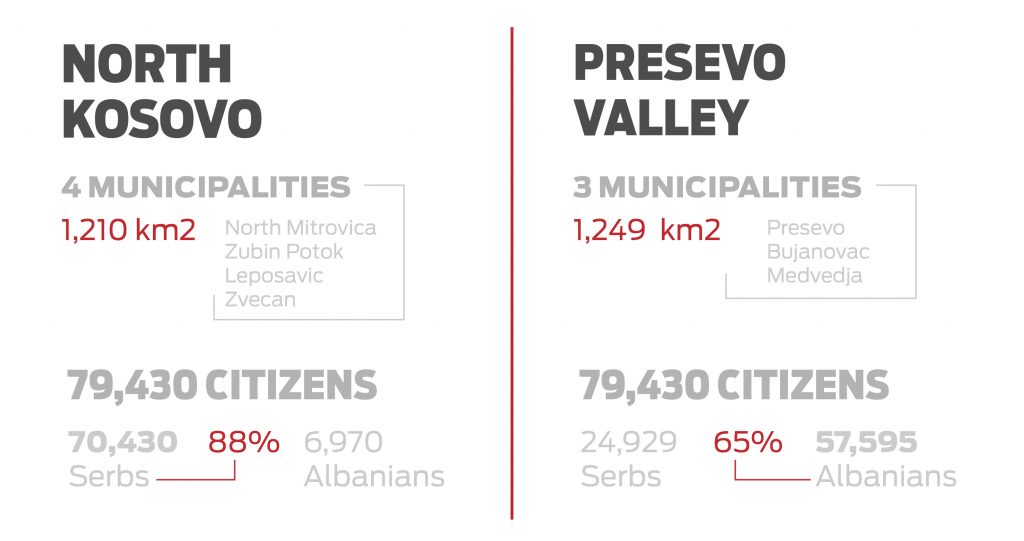

Both Presidents’ statements on the Presevo Valley and the northern part of Kosovo are based on a presupposed ethnic composition of the populations in the two areas. North Kosovo is inhabited by a Serb majority, while Presevo Valley is inhabited by an Albanian majority. But neither of the territories is monoethnic. A considerable number of Albanians live in northern Kosovo, and just as many Serbs live in the Presevo Valley.

North Kosovo is composed of four municipalities with a common territorial surface of 1,210 square meters: North Mitrovica, Zubin Potok, Leposavic and Zvecan. The Kosovo census in 2011 did not include the northern part, but according to OSCE data, 79,430 citizens live in these municipalities – 70,430 are Serbs (or 88 per cent of the population); 6,970 are Albanians. The villages of Koshtova, Bistrice of Shala, Ceraje, Caber, Boletin, Lipe, Zhazhe and Suhodoll are mostly inhabited by Albanians.

Graphic by Trembelat for Prishtina Insight.

On the other side, the Presevo Valley is a territory composed of three municipalities with a common territory of 1,249 square kilometers: Presevo, Bujanovac and Medvedja. According to the population census of 2002, 57,595 Albanians (or 65 per cent of the population) and 24,929 Serbs live in these three municipalities in southern Serbia. Presevo is populated with a larger percentage of Albanians (or 90 per cent of the municipality’s inhabitants), Bujanovac is a mixed municipality inhabited by Albanians, Serbs and other communities (55 per cent Albanians), while Medvedja is predominantly Serbian (Albanians make up only 26 per cent of the population).

This data shows that a territorial swap cannot be an easy process. What will happen to Albanian villages in the northern municipalities, or with the Serbian population in the Presevo Valley? Although they seem to be monoethnic regions, more Albanian citizens live in North Mitrovica than in Medvedja, while more Serbs live in Bujanovac than in Zubin Potok.

Or perhaps President Thaci and Vucic have other ideas than swapping territories en bloc, perhaps partition village by village? There are many questions left hanging to which the presidents of the two countries have given no answers. The fear that the correction of territories could imply a partition house by house, village by village, has incited a reaction from the Albanian leaders from the Valley, who demand that this territory is treated as a whole.

Whoever speaks of correction is embracing a new wave of ethnic cleansing. Such territorial swaps would not be a correction of borders, but the beginning of new inter-ethnic conflicts, a chain reaction of which could be repeated from Greece in the south, all the way up to Croatia in the northern tip of the Balkans. States should not be built on the idea of mono-ethnicity, but on liberal principles such as equal rights for all their citizens.