An interview with historian Shannon Woodcock, whose new book ‘Life is War,’ chronicling stories of Albanian people who lived under communism, is out now.

I wanted to start this article with a story from my family history. It’s a story about a branch of my family that lived in Albania during communism. They were torn apart, stripped of their wealth, and one particular relative ended up spending the rest of her life in a work camp. I can’t share the details of their story here, because it’s not my place to tell it. It’s one of the many stories that illustrate the systematic and meaningless violence that destroyed thousands of Albanian families from 1944 to 1991. How can this pain be given meaning? How can these stories be exalted, and who has the right to tell them?

Australian historian Shannon Woodcock spent six months in Albania talking to around 200 people in 2010, interviewing them about their day to day lives under communism. Six of their stories are chronicled in Life is War, Woodcock’s latest book. In Albania, a country infamous for its brutal and long-lived communist dictatorship, the victims of the regime coexist alongside their former jail keepers – with no real space to tell their stories or meaningful access to justice. I sat down with Woodcock two days after her book launch in Tirana to discuss Life is War and how it explores the intersection of trauma, history and justice.

Woodcock first visited Albania in 2003, when she was assigned a visiting lecturer position at the University of Tirana. During her two years teaching in Albania she completed her dissertation on anti-Roma violence in Romania and taught European history in Tirana and Elbasan through postcolonial theory.

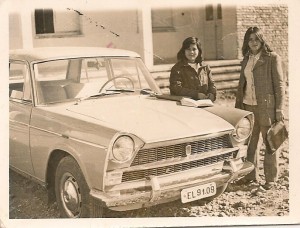

In 2009, she came to Albania again, to visit friends and colleagues. While visiting a friend’s family in Durres, the grandmother of the family began telling her about her life under communism. She told Woodcock about how her entire family became political prisoners when the communists took over. She told her about how she was put to work at the age of fourteen. She told her that she only had one dress to wear, which she washed in seawater after days of hard labor. “The men and women worked and slept all together” she stresses, “Do you understand me? I only had one dress.” She leaves the room in tears, but returns with a stack of photo albums and proceeds to tell Woodcock her family history.

Woodcock describes this moment as an “accident,” but one that prompted her to record the oral histories of Albanians who lived through communism. With the help of Albanian research assistants Eriada Çela, Edlira Majko and Besiana Lushaj, who came to most planned interviews as chaperones, translators, and who did post-interview transcription work, Woodcock recorded anyone who wanted to share their story. “I was here [in Albania] for six months, and I gave myself the rule that I would speak to anyone who wanted to talk. So anyone who said to me on the street, nga ku jeni? (where are you from), I’d say nga Australia (from Australia). They’d say, çka bën? (what do you do), and I’d say jam historiane dhe po shkruaj një libër për atë kohe, për periudhën e monizmit (I’m a historian and I’m writing a book about “that time,” about the period of monism) and then they’d say uau, po unë mund të flas për atë kohë (wow, well I can talk about that time),” she explains.

Life is War chronicles the lives of people who remember the rise of the communist regime, those were born in the midst of the regime, and those left grappling with the regime’s legacy in the present day.

The book opens with Thoma Çaraoshi, a Vlach Albanian from a wealthy shepherding family. Mevlude Dema, a chemist from a family with a “bad biography” is the second voice in the book. Diana Keçi and Liljana Majko, the voices in the middle section of the book, were both teachers and were both born during communism. Keçi, who once was a young woman with sincere socialist ideals, tells the story of her family’s fall from grace. Majko, a Roma woman, describes a life of backbreaking poverty and discrimination.

Woodcock’s meetings and interviews took her from the center of the regime’s power, Tirana, to its most desolate outposts. In places like Dragot, the families of political prisoners still face the economic and social isolation handed down to them by their ancestors, several generations later. In these stories, the contradictions of the regime are laid bare.

Enver Hoxha’s allegedly classless society had created new groups of the oppressed: the deklasuar (the bourgeois that needed to be reformed into ordinary laborers), the kulaks (landowners – regardless of size – whose land was taken away from them), and the alleged foreign agents and enemies of the state. Membership in any of these groups stained families for generations, without any hope of rehabilitation in the eyes of the state, as Woodcock explains. By 1990, 40,000 people had been sentenced to labour camps, and tens of thousands were subject to internment.

If you were persecuted once you were persecuted for three generations, right to the end. You inherited persecution and you could not claim any kind of rehabilitation. Woodcock

“I started researching whether there was a concept of rehabilitation, and there was not. In Romania it was different. People went to prison for certain amounts of time in the ‘40s and ‘50s and then they were considered rehabilitated even though they’d been tortured,” explains Woodcock.

“But Albania was such a smaller population and they maintained control by keeping – if you were persecuted once you were persecuted for three generations, right to the end. You inherited persecution and you could not claim any kind of rehabilitation. It was not built into the ideology,” Woodcock says.

The regime, as Woodcock explains, had to create both a working class and a new persecuted class. The irony of course being that a regime based on the ideal of classlessness consolidated power through the creation of deep class divisions – divisions that continue to the present day.

“It was clear to me from the moment I arrived in Albanian society that people identify by class, now obviously, and also retrospectively. That’s what I found when I arrived in the university [of Tirana and Elbasan in 2003], that all the students were identified by their social class in the ‘90s, but that was entirely contingent on their social class before. You can’t have been poor before and rich after. It was only a continuation of the same story,” she says.

The stories told in Life is War challenge another myth about the communist regime: women’s emancipation. Women were employed, but expected to continue their domestic labour alongside their work in the fields and factories. All forms of contraception and abortion were illegal. Diana Keçi explains how she had to seek an illegal abortion in Albania, one that caused a life-threatening infection. Other women interviewed by Woodcock explain how they tried to induce abortions by piercing their uterus with needles, or by ingesting herbs, medicine and poison. Liljana Majko describes how she had to participate in “voluntary” labour and military training until the final month of her pregnancy, as did all women.

Women who became prisoners of the regime were raped, beaten, tortured, forced to ingest hallucinatory drugs and did relentless hard labour during their imprisonment. Albanian authorities also ensured that women were directed towards “feminine” jobs such as midwifery or teaching. Resisting sexual assault or harassment in the workplace could have severe consequences, especially for women with suspect political backgrounds.

So how do these women feel now, I ask Woodcock. Are they angry? Do they want the past to stay in the past? How difficult is it to bring these stories to light?

“People said to me: women were emancipated into having two jobs, at home and in the labour force. All the old women, the women who are now in their 90s and passing away, they had no trouble saying we always did a lot of work. But after the emancipation you had to work while you were pregnant, all the way up to giving birth,” Woodcock says.

I ask Woodcock about the commonly accepted claim that communism provided a better social safety net for Albanian women, compared to the years of chaos that followed the fall of the regime.

“I think the discourse that it was better then [during communism] for women is an entirely post-socialist capitalist discourse and it’s because the 90s were violently unsafe for women. When people speak here, one of the things you learn is things were better under communism because in that time women could walk down the street safely. Yeah, it’s true in the 1990s people were picking women off Rruga e Elbasanit on the way to the faculty. But under communism, they were more likely to blackmail you to have sex with them while you were working in retail, and if you didn’t agree you got sent to a cooperative with hard labour,” Woodcock says.

During our conversation Woodcock described the fall of the regime as a period of “massive ideological abandonment.” All the voluntary labour, military exercises, food shortages and hard labour had been a farce, a slap in the face of those who believed in the mission of “building” Albania and those whose lives were destroyed for its sake. And what about all those Party men who sustained the lie? Who will exact justice for Thoma, Mevlude, Diana, Liljana, my family?

“The problem in Albania is that those who are in power in both political parties in the ‘90s are those who did the sexual violence against women in prison and are the people who ran the communist state. There’s been no change in power. So there cannot be any recognition of the violence, and those people who committed the violence are still fighting amongst themselves for power,” Woodcock says.

Be that as it may, Life is War achieves the opposite of what the regime intended: keeping its violence hidden and its narrative unquestioned. The lives presented to the reader in the book were subjected to a system that aimed to not only destroy them but any trace of their memory as well.

The book’s final story belongs to Jeras Naço, who tells Woodcock how he searched for the bones of his executed father after the regime’s fall. All he has left of his father during the time of his interview is his passport, a mirror and a spoon.

You asked me how justice would look for me today. The heavy feeling that I can’t answer that, or even grasp what it would look like, was relieved by talking to you. I feel relieved because the dignity of my father is being put in place by being part of your book. Jeras Naco

He contemplates justice at the end of his chapter: “You asked me how justice would look for me today. The heavy feeling that I can’t answer that, or even grasp what it would look like, was relieved by talking to you. I feel relieved because the dignity of my father is being put in place by being part of your book.”

Woodcock’s intention with Life is War besides the documentation of pain and violence, is the stubborn beauty each of these lives contained.

“I wanted to write a book which reflected the way people themselves reflect on their lives. We don’t see our lives as one big mess after another. We don’t see our lives in terms of who was in power in the government … if someone was to ask us a question in an interview – like what was your first break up – a requisite for telling that story would be why you were in love with that person in the first place. You can never take the beauty out of your youth or out of the past. And I wanted to put that in the book, to show that people lived. That’s the story I’m interested in telling and that’s the kind of book I want to read.”

Woodcock is still gathering people’s stories, and encourages others to record their own stories as well. She can be reached via email: [email protected]

“Life is War” is available through Hammeron Press and Amazon, in print and e-reader format. The Albanian translation is forthcoming.