For more than three decades, Fahri Musliu was among the only Kosovar voices reporting from Belgrade. After returning to Prizren, he faced another task: fueling a new political alternative.

Fahri Musliu’s career has gone by so quickly that when he recalls the first news article he wrote, he cannot believe that it was 50 years ago.

As a high school senior, a tall, young Musliu put his joy into words when he wrote about a grain and flour shop that was opening in the neighboring village of Bresana, Dragash in March of 1967. He had written the news article with a pencil in a notebook, and when Rilindja, the only national daily at the time, published it, Musliu felt that something big was coming his way.

“At the time, it was some majestic news,” he said, half a century later, chuckling at the relevance of the article at the time that it was written.

But upon graduating high school, it was not as if Musliu knew he’d one day join Rilindja’s ranks as a correspondent. Instead, in 1972, he applied for an administrative position in the village of Bresana. Although he got the job, he was blocked from taking it because a year earlier he voted against someone becoming the Party Secretary of Dragash.

“I thought that power should not be dependent on the individual,” said Musliu on his youthful act of rebellion by voting against a party member.

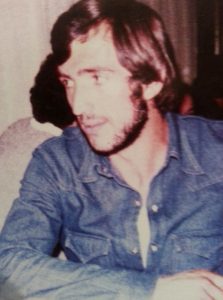

Fahri Musliu in 1976. | Photo courtesy of the interviewee.

It was the Party Secretary who blocked Musliu from taking the position. He applied for a second time, got the job once more, but was once again vetoed by the party official.

Musliu realized that his career as a local public servant had ended without ever starting. The petty decision might have been a blow at the time but ended up leading Musliu to a more dynamic life path than being an administrative employee in rural Opoja.

In search of other career paths, Musliu stumbled upon an open application to enroll at the department of journalism at the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade.

When he got accepted to the faculty, he realized that studying was expensive and his family would not be able to pay for his studies in a faraway city. Instead, he decided to do distance learning while he was in Belgrade.

“I needed to work to support myself and my family,” Musliu said, recalling that he had left behind his wife and six-month-old daughter in the village of Zaplluxha, Dragash.

Belgrade as a city and Kosovo Albanians as a population had each experienced tumult and change during the second half of the 20th century. The city was not always welcome to Albanians.

A textbook poem taught to Kosovo Albanian schoolchildren reminded them that if they wanted to go to Belgrade, they must get their saws ready, as many Albanians, uneducated and poor, only managed to get work as manual laborers in Yugoslavia’s capital.

Others tried to offer a counter narrative.

I never felt inferior in Belgrade, quite the opposite. I felt superior even to academics and other journalists. I always got into polemics.

Bekim Fehmiu and other actors provided a different role model on the theater stage, Luan and Xhevat Prekazi, Fadil Vokrri and others on the football field, all while seemingly shutting out the difficult times experienced by the Albanians in the city, which had started to give off and internationalist vibe.

Meanwhile, Musliu decided to choose a third road – to walk through the streets of the metropolis of the former federation with a tie on his neck and a backpack on his shoulders.

“I never felt inferior in Belgrade, quite the opposite. I felt superior even to academics and other journalists. I always got into polemics,” he said.

From the early ’70s, Musliu wrote for Kosovo newspaper Rilindja, and then later when the newspaper was closed he wrote for Zeri before finally working for Kosovo public television, RTK.

During the 1990s he also worked as a correspondent for the Voice of America.

In the cold days of March 1999, when NATO began its bombing campaign on former Yugoslav military points after Milosevic refused to accept the Rambouillet deal, Musliu’s own situation changed, as did the city he lived in.

Musliu found himself in Belgrade and his profession told him to not move an inch.

Eighteen years later, he says that he does not regret his decision, although a few foreign embassies had offered him the possibility to leave when it became clear that the NATO bombings were inevitable.

“No, I did not leave, due to my profession. For a journalist outside the newsroom, reporting from a warzone is something big,” he said. In 1999 Musliu was a correspondent for the Voice of America, which would soon enough cause him grief.

During that spring, when the military had everything in their hands and journalists were prohibited from reporting to foreign media, his days followed the usual routine of staying in his room, without much possibility to move around except to a cafe here and there with friends.

He even received threats through his flat’s intercom.

“There were many phone calls: ‘Where are you, why are you waiting, we will kill you…’ I would tell them: ‘I’m here waiting for you.’ To fear is human, but I was never afraid. Although, an excessive lack of fear is foolish,” Musliu said.

While he himself was living for tomorrow, he worried most about his wife and children he left behind in Prizren.

“There were not many Albanians in Belgrade at that time, because they started to get attacked. Within two or three days, most of them fled to Bosnia and Romania.”

The Belgrade that had received him with open arms in the ’70s was nothing like the one in those days.

In the “olden days,” as he refers to the period, though people suffered under the Yugoslav communist regime, the city was abuzz was international artists.

In ‘democratic’ Belgrade, he received death threats and could not conduct his work. Furthermore, in that same Belgrade, plans were being made to carry out ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. The atmosphere in Belgrade in June 1999 was especially tense.

“People with a conscience knew that Milosevic would capitulate,” he said.

Retirement and involvement in politics

Sitting at Hotel Theranda’s restaurant in Prizren’s city center, a place where he often spends time with friends, Musliu said that he cannot imagine life without dynamism.

Simply put, retirement did not work for him.

As in Belgrade, in Prizren he also wants to debate, to polemicize. Be it in intimate groups, or through discussions on social media.

Last month, he ended a few year’s long silence when his name name appeared on the initiating council of the Prizren branch of Kosovo’s new political party, Alternativa (the Alternative).

The party, co-led by Gjakova Mayor Mimoza Kusari-Lila and independent MP Ilir Deda, is running for the first time in the June 11 general elections in a coalition with the Democratic League of Kosovo, LDK, and the New KosovoAlliance, AKR.

Although Musliu is not on the MP candidate list, he still considers the new party a shelter where he can push his ideas forward. One of them is the cooperation of all of Kosovo communities through one structure.

A city once covered in stone, but now replete with concrete, Prizren, retains a dormant element of multi-ethnicity. Musliu wants to awaken the city’s spirit through a common project.

He succeeded to include Bosniak, Turkish and Roma representatives in Alternativa’s Initiators Council in Prizren.

During his tenure as the leader of the Democratic Party of Kosovo, PDK, Hashim Thaci had once called Prizren “the party’s Jerusalem.” But one could easily argue that after Prishtina, winning Prizren is every party’s goal.

“Here, the votes of non-Albanian communities determine the mayor,” said Musliu, admitting that Prizren is not only different in architecture, but also politically. “The Bosniak community has a high potential, as do the Turks and Roma.”

Fahri Musliu in Prizren. | Photo: Perparim Isufi.

However, based on his observation, not even the members of these communities are satisfied with the representatives they have chosen. This is why he thinks that the voters of these communities need a political alternative that overcomes ethnic borders.

“There are many who are interested to become members and to make an effort to make changes, because in Prizren, in one way the Ahtisaari plan is being implemented to a T, in the sense of internal ethnic division,” he said.

Various cultures in Kosovo have been intertwined for centuries in the southern city, which until 1947 was the capital city of Kosovo.

In the plan to solve Kosovo’s status, the former Finnish President Martti Ahtisaari obliged state institutions to give a portion of Prizren a special legal status in an effort to protect the cultural and religious heritage of the city.

Musliu believes that many communities have been isolated by the creation of various ethnicity-focused cultural organizations, and that the ethnic lines of the municipality have gotten firmer.

An initiative for creating a municipality with a Bosniak majority in the group of villages along the road to Prevalla would, according to him, be the epitome of creating ethnic division.

“Communities are dividing, they’re not uniting… there will no longer be a mono-ethnic municipality in Kosovo, because there is no such thing even in the world. And if a member of another community lives in that Municipality, he will not feel comfortable,” he said.

Sliding towards the bottom

Musliu expressed his disappointment about the way things have been going in Kosovo ever since the country became independent in February 2008.

“As a country, Kosovo is sliding towards the bottom. The Kosovar society is walking towards a blind alley,” he said.

Musliu’s situation at home mirrors the crisis outside.

His daughter, who pursued an MA degree in Psychology five years ago, is struggling to find a job. Until now, she has found no luck.

“There are no jobs. There are 15 members in my family who are eligible to work, and only two or three of them are employed… qualifications are not considered, rather the political or family connections are,” he said.

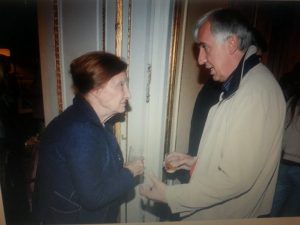

Fahri Musliu and Latinka Perovic in 2008 in Belgrade. | Photo courtesy of Fahri Musliu.

Now that he has entered politics, a step not so unusual for journalists in Kosovo, Musliu said that with nothing ventured, nothing is gained.

“It is something new but it is a bit risky,” added Musliu.

However, in the first weeks of his engagement with politics, Musliu noted that there is “a huge potential” for those who are active. Generally this refers to dissatisfied people, one of which is Musliu himself.

“In Kosovo, even the ones who are rich are unsatisfied because they have this fear coming from somewhere,” he said.

Musliu said that the June 11 snap elections are engulfed in political polarization. The forthcoming elections will find most of the member parties with an electorate somewhat consolidated, and with other parties such as Alternativa in search of their own electorate.

The latest polls are giving Fahri Musliu a glimpse of hope.

“Almost half of the electorate aren’t determined and this is our cue,” he said.

However, Alternativa, according to Fahri Musliu, does not have anything to do with what the other parties have so far done with the politics of ‘voting for employment.’

I told young people: do not enter Alternativa if you believe that the party will ensure jobs for you. Forget about that.

He said that he also told this to the youth who became members of the Alternative. “I told them: do not enter the party if you believe that the party will ensure jobs for you. Forget about that.”

Musliu has published a few books throughout the years. One of them is a diary of his days in Belgrade during the NATO bombings. Another one is on the artistic figure Bekim Fehmiu. Some others are manuscripts waiting to be published.

However, he hasn’t said it all.

“Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find myself in the Kosovo journalism scene, which is sliding into unprofessionalism,” he said.

“There are no more professional journalists being produced,” he added.

While he drank the last sip of his espresso, he recalled his last day as a journalist with a contract with the public television broadcaster RTK.

He said he wouldn’t wish that day on anyone as an end to mark a career.

“They hadn’t even invited me to say goodbye, to have coffee. Or even to tell me to go to hell,” he said.