How a community united to get a generation of marginalised children into classrooms.

Anyone who has spent five minutes in Kosovo’s capital has seen them: beggars with outstretched palms set up on the cold stones of Nene Tereza, scrappy smiling kids cracking jokes in the hopes of getting a few coins. We know by now that we’re not supposed to give children money, so we pass by and they recede into the rhythm of Prishtina, part of the buzz of peddlers, hawkers, musicians and gamboling toddlers that mark the soundtrack of our strolling lives. We usually don’t learn their names or ages or lives.

Most expats in Prishtina probably arrived wanting to help them, motivated by idealistic aspirations of becoming immersed in a foreign culture, finding fulfillment and making a difference. But enthusiasm for learning a new language generally wanes with 40+ hour workweeks, and confronting the labyrinthine bureaucracy of a post-socialist system can seem Sisyphean. And, how would you really go about befriending a beggar child?

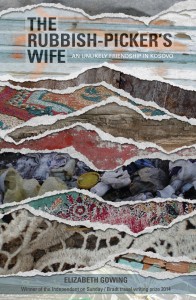

Elizabeth Gowing struck up an unlikely friendship with a group of these children, and their parents, which is the subject of her most recent book, The Rubbish Picker’s Wife. In this memoir, Gowing, an Englishwoman, spins a powerful narrative about how a chance encounter with a child and his illiterate mother led her to become immersed in one of the poorest communities in the poorest country in Europe.

Gowing didn’t come to Kosovo on a crusade, though she did make it a priority to learn Albanian and later, Serbian. On a visit to drop off some second hand items, the body of a burned child was thrust in her face by his desperate mother, Hatemja (who provides the book’s title and whose family story becomes its core). Gowing could not turn away from the child, whose abject poverty and abandonment by the state would likely have rendered him fated to remain poor, scrounging, as his father did, through the trash bins of Prishtina for material to recycle. The children, the Rubbish picker whose name is Agron, explains, were not in school because they didn’t have shoes.

Gowing was then in ‘Neighborhood 29,’ a predominantly Ashkali community in located in Fushe Kosove, mere kilometers from the institutions (local and international) in Prishtina who are supposed to be dedicated to helping marginalized citizens of Kosovo.

Gowing purchased shoes but made a deal that she would be checking on the progress of the students. Then, she found out that school age siblings of the burned boy, Ramadan, had not been registered for school and were now, at nine years old, too old to register. Because of a government policy stating that those who had not registered by the time they were nine, many children who wanted to attend school were being turned away by Kosovo’s education institutions. Gowing, who had been a teacher and school director in England before moving to Kosovo, set up a temporary classroom so that they could catch up, and simultaneously began lobbying the schools and institutions to get them registered the following autumn.

Ramadan’s siblings were not alone: eventually some 70 children who weren’t in school but wanted to learn were coming to her center each day, hungry for knowledge and for the respect that education brings.

With community partners, Gowing set up an NGO, The Ideas Partnership, and began fundraising. Teaching them to read was only half the battle: she needed to convince the school system to take the children as well, which was not easy. In their quest to register 62 children for school, they faced inane obstacles so infuriating that the reader wants to scream. Gowing had encounters with prejudiced school officials and lazy education ministry employees before then-prime Minister Hashim Thaci himself intervened to overturn the 9-year-old policy and guarantee the right of all children to go to school. When they were told they would be able to access education, and that they would come home with homework, the children clapped and erupted into cheers.

Eventually, Gowing and her colleagues set up a soap-making micro-finance project, which provides an income for women so that their children can attend school and are spares them from begging in the streets.

They also set up a small fund to provide medical care to those most in need, hire a medical coordinator, and try to assist women, some with at least five children, with family planning. At first she just accompanied community members to the hospital, insisting that they be seen by doctors and not dismissed due to prejudice. Later, she ran into different resistance from Muslim religious leaders in Neighborhood 29, who disapprove of birth control. On the other hand, Gowing also rails against the headscarf ban imposed in Kosovo, which prevents girls who would otherwise go to school from getting educated.

Later, the organization built a little kindergarten, continued weekend classes for kids, and continues to be a positive community space in a place where there are few options for collective action aside from the home.

Gowing’s tales are far from self-aggrandizing. The author is self-aware and shares her insecurities, her doubts, and her struggles in being a community member but also a kind of donor, sharing her worries that some of her relationships are uneven since money and prized resources are involved. She acknowledges the presence of her own ego and her fear of failure. It is in these deliberations that the book also shines, because it reveals that any one of us who has both a heart and a head, as well as strong supply of determination, can actually change the world.

Gowing’s most important achievement is to give faces and names to members of the marginalized Ashkali community, who with dignity, charity and perseverance summoned their own strength to change the world, making their community cleaner, healthier and more literate. The book is primarily about this small group of people in a small corner of Europe who fight prejudice, corruption and ineptitude and win small victories to change their communities.

Indeed, to paraphrase Margaret Mead, it is the only thing that ever has.

01 December 2015 - 13:00

Following the ban of last year’s edition in Belgrade, the 12th editi...

A new movie about a rebellious teenage girl’s coming of age tells a ...

Politicians have joined figures from the arts and acting world in payi...

The Sunny Hill Festival took over Kosovo with its organiser, UK-born K...