Having learned to read in 1943 aged 14, Daut Islami later entered into a more than 40-year long career as a teacher that spanned the second half of the 20th century.

Daut Islami vividly remembers the summer of 1943. One day, towards the end of July, he was out with his relatives shepherding his flock in the Sharri mountains in southern Kosovo, when a group of Partisan soldiers approached them.

With World War II ongoing, Yugoslav Partisans were involved in sporadic skirmishes with Axis troops in the region and Daut, aged 14, was a potential recruit.

Islami tells BIRN that the soldiers were sent personally by Fadil Hoxha, one of the founders of the Partisan movement in Kosovo who went on to become a prominent political leader following World War II.

As well as teaching Daut and the other older shepherds how to fire guns, the Partisans also brought with them something that would shape Islami’s life – elementary school textbooks in the Albanian language.

Now aged 91, Islami recalls nostalgically the events that took place nearly eight decades previously. It was the first time in his life he had touched a book.

Highly curious, learning to read and write quickly became an obsession for Islami. “Within the month, me and my friend Shukri managed to learn all 36 Albanian letters up there in the mountain huts,” he remembers.

Illiteracy was common in Kosovo in the 1940s, but things were starting to change, even under the occupation of the Axis powers. Between 1941 and 1944 hundreds of teachers from Albania were sent to fight illiteracy in Kosovo. More than 170 new primary schools teaching in the Albanian language were opened, and the first textbooks in Albanian started to be used.

However, fighting illiteracy was an enduring battle for Kosovo Albanians. According to a 1948 census, 74 percent of Kosovo’s population was illiterate.

Following the war, Islami attended one of the newly opened schools, completing the first four years of primary education between 1947 and 1951. “There were only 31 pupils back then and only four girls,” he says, recalling each of the four girls by name.

Islami then completed a two year course at an administrative school in Kacanik, obtaining “excellent results.” One of his former teachers there also worked in the community battling illiteracy in the Ferizaj region, and in the early 1950s, Islami was asked to join him in this goal.

Then in his early 20s, teaching people to read and write soon became a mission for Islami, but he remembers that it was a surreal experience teaching the alphabet to people some of whom many years his senior. “In these villages I taught people to read and write and all of them were 20 or older,” he says.

A lack of resources also made teaching difficult. “All the students were sitting on stools and I had a piece of wood as a blackboard,” Islami says. “There was one textbook and one notebook, and I went to each of the pupils to practice writing and reading.”

He adds that many of the students did not have access to writing implements at this time. “Sometimes I broke the pencils in three just so everyone had something to write in the notebooks with,” he tells BIRN.

By 1953, Islami was 24 and working as a teacher in the villages surrounding Ferizaj and Lipjan, the beginning of a career which continued for the next four decades.

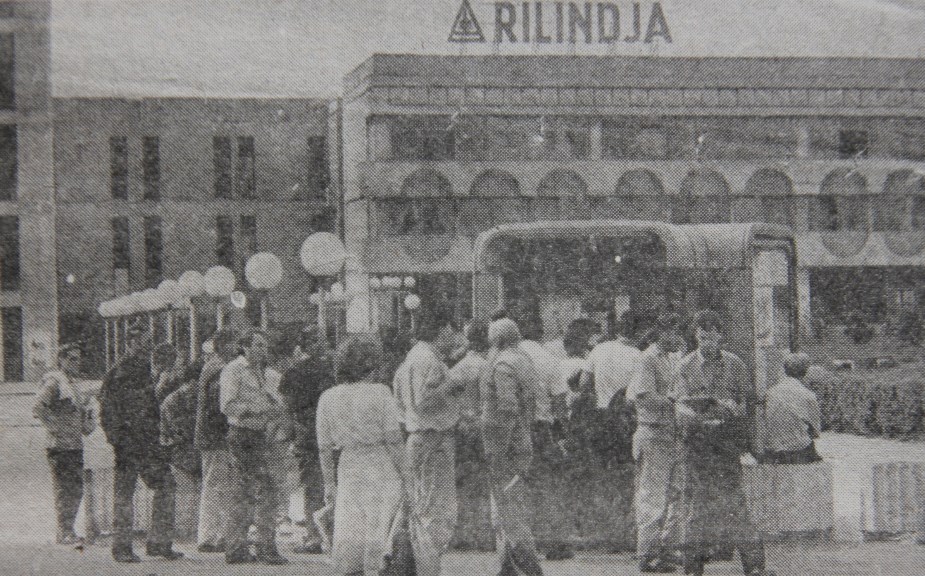

He remembers the 1970s and 1980s as a particularly good era for education in Kosovo, partly due to the Rilindja printing house in Prishtina, which published a wide range of educational materials for children. “I supplied many primary schools with textbooks through Rilindja as I had some connections there,” he remembers.

This period saw a drastic drop in illiteracy rates in Kosovo. By 1981, only 17 percent of Kosovo’s population were not able to read and write, down from 74 percent in 1948.

Dark days and retirement

But as Kosovo moved into the 1990s, this progress was halted. In 1990, the RIlindja Printing House was forcibly closed by the Serbian regime following the withdrawal of Kosovo’s autonomy by Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic in 1989.

For the 1990-91 school year, teaching was segregated along ethnic lines, with Kosovo Albanians educated in the afternoon and Kosovo Serbs in the morning. The ongoing repression and violence against Kosovo Albanians throughout the decade pushed many to abandon education.

According to Tim Judah’s book Kosovo: War and Revenge, by the 1995-96 school year there had been a significant drop in pupils enrolled in schools compared to 1989-90, including 12 percent fewer primary school students and 21 per cent fewer high school students. By 2000, illiteracy rates had risen to 20 percent.

For Islami, this led to what he describes as a “dark era” in the five or six years leading up to his retirement in 1995. He was back teaching in the place of his birth, Firaje, a village in the mountains near Strpce – a remote location that was still not free from the fear of police clampdowns on educational institutions.

By 1992, the school had become part of Kosovo’s parallel education system, operating outside of state structures. “We had to close the curtains and stay in darkness using candles, just to make sure that the police wouldn’t notice us if they were patrolling in the neighbourhood,” he remembers.

Even after Daut’s retirement, teaching has continued in the Islami family with four of his six children entering the profession. However, he still regrets that one of his daughters chose to become a dentist instead.

Islami has seen a huge range of people pass through the schools he worked in. “I taught people who became doctors, professors and economists,” the 91-year-old says. “Some of whom are still alive, and some of whom have gone.”

Despite the challenges he faced, Islami says that his commitment to education was a fulfilling experience. “It was a joy teaching the students because most of them were family members or neighbours,” he reminisces with a smile. “I got a lot of happiness from seeing them learning to read and write and becoming more knowledgeable.”