Prishtina Insight sat down with Sezgin Boynik, the editor-in-chief of Finnish radical publishing house Rab-Rab, which launches the fifth issue of its political art journal in Prishtina on Thursday.

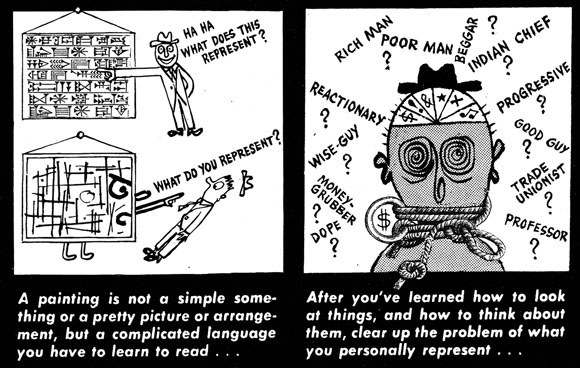

Describing the vision behind Finnish political art journal Rab Rab, its editor-in-chief, Sezgin Boynik, enlisted the help of abstract artist Ad Reinhart. In his lifetime, explained Boynik, Reinhart wrote comic strips when he wasn’t creating his famous black-on-black paintings.

One of his comic strips featured a conservative, hat-wearing bureaucrat in a gallery, pointing his finger and laughing at an abstract painting, saying “ha, ha, what does this represent?” In response the painting becomes angry, points back at him and yells “what do YOU represent?”

According to Boynik, the most valuable thing about contemporary art is being able to openly discuss what it represents, and it’s not happening enough. Encouraging political conversation and critique around artistic works without being elitist is what Rab Rab is trying to accomplish.

Rab Rab, officially called the Journal of Formal and Political Inquiries in Art, will be launching its fifth edition at the social center Sabota in Prishtina on Thursday evening.

Sabota, a social center in Prishtina run by an independent collective with a leftist political philosophy, hosts discussions, film screenings, presentations and parties from its small base in Ulpiana.

The first edition of Rab Rab was published in 2014, and since then, Rab Rab has produced texts decoding the language of Vladimir Lenin, exploring the socialist resistance of Finland’s paper factories and deconstructing Russian experimental children’s books, bringing pockets of history that people know nothing about to the fore.

One element of Rab Rab’s philosophy is to support alternative spaces for artistic, research-based discussion.

“Nowadays in Kosovo, there is a lot of interesting things happening, but not quite on that [desired] level,” said Boynik. “The idea was to bring some art projects together that do not rely on institutions, whether commercial markets or gallery spaces. We want to move the ideas around art a bit further into politics, into theory.”

Boynik, a sociologist based in Helsinki, has been involved in projects in Kosovo through Dokufest, Kino Armata and Stacion, working to slowly make space in Kosovo’s cultural life for critical approaches to art.

The Rab Rab issue presented on Thursday will feature “stories about nation traitors, fierce masses, socialist women struggles, love-forms, psychedelic counter-revolutionaries, workers unions, Brecht fiddlers, jazz surrealism, Soviet trains, and anti-fascism,” with Boynik and others giving presentations on various sections of the journal.

The motto of Rab Rab is that anyone can write, said Boynik. “Anyone can come to us with the smallest spark on an idea, we’ll dig into it, discuss it, research it and help to create it.”

This flexibility makes it easier for people to identify with the work. “You slowly develop a connection with readers that is lasting,” said Boynik. “It creates an invisible community of people. Today, everything has to be marketable, sell-able objects, it’s difficult to find people that are happy to slowly engage, who actually want to contribute to art without thinking about how to be a part of that market.”

Non-commercial explorations of abstract and theoretical art, writing and research is what Boynik hopes publications like Rab Rab can promote in Kosovo.

Thursday’s launch is particularly important, as Boynik will also launch three works produced by a new publishing house located in Prizren, Shuplak Shuplak, or ‘Slap Slap.’

Opened with Tefvik Rada and Vernon Shukriu, the publishing house was named after Vladimir Mayakovsy’s 1917 manifesto, ‘A slap in the face of public taste.’ Shuplak Shuplak will produce works centered around Kosovo and Albanian history, with themes both avant garde and political that have universal or global reach.

One example, Boynik revealed, is a translation of a book published in Russia over one hundred years ago about Albania, expressed in Dadaist language, a “revolutionary avant garde text” providing commentary on war and anti-imperialism.

Shuplak Shuplak will also publish a text reviving the poetry of muslim religious leader Haxhi Ymer Lutfi Pacarizi, whose poetry was considered a turning point in the early twentieth century towards the Kosovo muslim population’s support for the Yugoslav communist party.

“He wrote beautiful poems expressing that communism is a salvation for the Balkan population, that it will transcend them from nationalist and religious stupidities, and show that wars are for nothing other than filling the pockets of rich people,” said Boynik.

The third text to be released will follow the journey of the Scratch Orchestra, a British musical group that began to support the communist ideology of Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha in the early 1980s, who came to Albania to record an album of experimental Albanian folk and revolutionary songs, ‘Albanian Summer.’

Shuplak Shuplak’s texts explore the lesser known corners of Albania and Kosovo’s past, and Boynik hopes that they will resonate with people here.

“Some say that my projects are very elitist, because they deal with experimental music, structural films, abstract and geometric non-objective paintings, Dadaist sound poems,” said Boynik, “but I’m always grounding them into some political situation or historical moment as a conjunctive.”

To him, abstraction is a means through which artists can represent their struggle to understand reality, rejecting the existing way that politics, art and language are represented.

Boynik rejects the belief that more abstract work can only be enjoyed by one exclusive segment of the population, and criticizes the existence of artistic institutions that push this kind of art out of reach for many people.

“Ignorant art critics would say to Marxists and revolutionaries engaged in experimental art ‘The people that your work is targeting, they don’t even understand your stuff!’ But the more I research, the more I am convinced that the bourgeoisie as a class is the most ignorant, most philistine, and is the most regressive in their cultural likings,” he said.

“In fact, it is the workers, the masses that critics would say have no cultural connection with existing institutions, that understand these things even better.”

Rab Rab’s explorations of politics and art can be a doorway to more inclusive discursive practices in Kosovo, said Boynik.

“Everyone can understand art, as long as they can speak about it with others,” he said. “If there’s some other world that we don’t know much about, then we should try to understand it.”

Rab Rab will present the fifth issue of the Journal for Political and Formal Inquiries in Art at 20:00 on Thursday at the Sabota social center in Ulpiana. For more information, see their even on Facebook.