During the ‘90s, Albanians in Kosovo and the diaspora showed tremendous solidarity in helping one another. Why did this solidarity wither after the war, and why is Kosovo assigning monetary value to the voluntarism and sacrifice of those times?

Following the revocation of Kosovo’s autonomy, the mass expulsion of Albanians from social enterprises, and the close down of Albanian-language schools, Kosovo Albanians entered the ‘90s without political and civil rights, without the right to an education in their own language and faced social and economic difficulties as a result of the mass dismissal from their workplaces.

But, it did not take long for Kosovo Albanians and the diaspora to mobilize and start establishing a parallel state. This parallel state would have a president, prime minister, government, and would collect income and finance ‘public services,’ including salaries for teachers, the allocation of social assistance for families in need, the creation of ‘home-schools’ as alternative methods of education,, the buying of school supplies, funding sports activities and other expenses.

What fascinates me most from that time is the readiness of citizens in Kosovo and the diaspora to voluntarily portion out part of their salary to finance the ‘parallel state.’

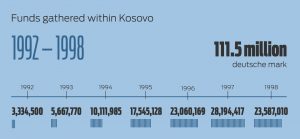

From 1992 to 1998, the parallel structures managed to gather 111.5 million DM in Kosovo on a voluntary basis.

A book published by Mehmet Hajrizi, Ismajl Kastrati and Bajram Shatri on the work of the Central Council for Financing in Kosovo, KQFK, provides interesting details about the process of collection and spending of funds during the ‘90s. The KQFK was established on February 7, 1992 to gather funds from citizens and businesses and distribute them according to necessity. Besides the KQFK, the ‘3 per cent fund’ was also founded, which collected money from Kosovo citizens in the diaspora.

The KQFK drew up guidelines that specified tax rates for each category of citizen, business and general family economy. According to these guidelines, every employed citizen was required to pay 5 per cent of her income for the KQFK. Every family economy was required to pay at least 5 Deutsche Mark, DM, every month. Additional 1 to 3 DM would be added depending on the amount of land the family owned; and on top of that, an additional 3 DM would be added for every hectare of agricultural land, like vineyards and other croplands. Family economies that had members employed abroad were requested to pay 15 DM per month for every expatriate worker. Independent service activities of a seasonal character, like electricity and portable water installers, masons, beekeepers, etc., were required to give 10-20 DM per season. Renters were required to give 10 per cent of their rent, while businesses assigned their contributions depending on their activity, circulation, area of activity and size of their business space.

KQFK was composed of 30 municipal financing councils, one in every municipality in Kosovo. Through their treasurers, the councils would contact citizens and businesses, and agree on the amount of contribution voluntarily. Considering that there was no element of obligation, except for social pressure, families and businesses agreed upon the amount of money according to KQFK guidelines. In an interview for Bujku on October 21, 1992, head of KQFK Mehmet Hajrizi stated that “for those who can generate an income it is a moral debt to pay to support teachers, and to support the families that have no means to go through this tough winter.”

In 1997, there were 282,603 contributors, 66 per cent of which were family economies, 15 per cent were employed and pensioners, 13 per cent were families with members employed abroad, and 2 per cent were stores. From 1992 to 1998, when KQFK operated, 111.5 million DM were gathered in Kosovo.

Source: Burimi: Mehmet Jarizi, Ismajl Kastrati, Bajram Shatri – “Këshilli Qendror për Financim në Kosovë”, Libri shkollor. | Illustration: Trembelat.

Yet, KQFK was not the only financing scheme. While KQFK was responsible for collecting funds within Kosovo, ‘the 3 per cent fund’ was created by the Kosovo government in exile, which collected contributions from the Kosovo diaspora in western Europe and North America. Every Kosovar citizen residing abroad was requested to portion out 3 per cent of their income for the fund. In addition, the “Vendlindja Therret” (Homeland is calling) fund was established in 1998-1999 to finance the Kosovo Liberation Army.

While there is greater transparency for the funds gathered by the KQFK, there are no reports on how much money was gathered by ‘the 3 per cent fund’ and the “Vendlindja Therret” fund, or how it was spent.

The only data that exists about ‘the 3 per cent fund’ was presented in a report by Hajrizi, Kastrati and Shatri, the founders of the KQFK, which concerns the collected funds and how they were spent by the KQFK. According to the report, the contributions gathered by the KQFK in Kosovo were insufficient to cover all expenses for the parallel schools, teachers, social assistance, and other cultural and sports activities. What was not covered by KQFK’s funds was made up for by ‘the 3 per cent fund.’ Consequently, between 1992 and 1999, 83.2 million euros were transferred from ‘the 3 per cent fund’ to the KQFK. Including the 4.8 million euros from donors, they managed 200 million DM between March 1992 and March 1998.

In 1997, the structure of the assistance program prioritised education with 91 per cent of the budget, allocating 2 per cent to social assistance , healthcare 1.5 per cent, giving culture 1.5 per cent, science and research institutions 0.6 per cent, sports 0.5 per cent, local administration 1.4 per cent and allocating political subjects 1.5 per cent.

The number of individuals who received salaries was 18,754 in 1992 and increased to 25,034 in 1998; most of them were employed in elementary and secondary education.

The average pay varied from 35 DM per month in 1992 to 170 DM in 1998. In 1998, the highest salary was that of a university professor, 330 DM per month, while the lowest was that of janitors, 125 DM per month. Due to the pay being in DM, there were periods when teachers in Albanian parallel schools earned more than teachers in Serbia, where inflation was very high and people were paid in dinars.

Many donors in Kosovo and the diaspora requested to remain anonymous.

Aside from providing salaries for teachers, the funds served to give social assistance to 600 families in need. During this period, 43 new schools were built, and there were investments in private homes in order to use them as schools. Furthermore, money from the “3 per cent fund” and KQFK was allocated to assist Albania after the upheaval in 1997.

Yet, funds collected through this method were not the only show of solidarity among citizens. During the ‘90s, the campaign “Shkolla ndihmon shkollen” (Schools help schools), united students and parents who were better off to help students and teachers in secluded schools in the mountains. Another initiative called “Familja ndihmon familjen” (Families help families) mobilized families in a better social standing to assist those that could not make ends meet.

In their report on the operation of the KQFK, Hajrizi, Kastrati and Shatri showed that there was a considerable number of teachers in the ‘90s who enjoyed better material wealth, and refused to be compensated for the work they did in schools in order to allow their colleagues to be paid. Similarly, families who were worst off did not accept social assistance and it was difficult to convince them to be part of the scheme.

Many donors in Kosovo and the diaspora requested to remain anonymous. There were also cases when families sold part of their property to finance education in the ‘90s. For instance, Isa Veliu from Sllubica, Gjilan sold one of his three cows and donated 500 Swiss Francs to the KQFK municipal council in Gjilan. Mustafe Lubeniqi, a retiree from Tomoc, Istog, donated 1,000 Swiss francs and insisted to remain anonymous, but his name was written by one of the treasurers from the municipal council in Istog. Latif Kryeziu, who used to work in Germany, gave 10,100 DM for education in Kosovo. Cases like these are countless.

Source: Burimi: Mehmet Jarizi, Ismajl Kastrati, Bajram Shatri – “Këshilli Qendror për Financim në Kosovë”, Libri shkollor. | Illustration: Trembelat.

Although contributions were gathered outside of financial institutions, there existed a high risk of confiscation and imprisonment in case the Serbian police caught KQFK treasurers and transfers were done in person, but regardless, the incidence of abuse and loss of money was very low. In many cases, physical persons who were chosen to withdraw up to 1 million DM in Tirana from Dardania Bank, where the funds collected in the diaspora were saved, carried the money in bags and illegally crossed into Kosovo in order to pay teachers, issue social assistance and cover other expenses. According to the heads of KQFK, during its seven years of operation, only 0.59 per cent of the fund was lost.

After the war in Kosovo ended, this widespread solidarity among citizens of Kosovo and the diaspora withered. One of the factors that had an impact was the high level corruption in local institutions, which signalled to others that that living with integrity was not worth it.

While under occupation, without a banking system and without security and judiciary institutions, only 0.59 per cent of funds were lost in seven years. After the war, annually around 10 per cent of the budget is lost in illegal expenses.

While under occupation, without a banking system and without security and judiciary institutions, only 0.59 per cent of funds were lost in seven years. After the war, with the establishment of government institutions and banking system, illegal budget expenses, according to findings by the National Auditing Office, are around 10 per cent annually.

The KQFK guidelines that classify families who needed social assistance was evidently much fairer and more inclusive than the current law on social assistance. The current law excludes families that have one person who is able to work and who do not have children under the age of five. In the ‘90s, families that had a high number of students, people of old age and who were ill were also given social assistance.

In the ‘90s, the humanitarian association “Nena Tereze” managed to identify and gather data on 100 thousand families living in strained circumstances. After the war, there still is no data on families in need and without shelter.

Although during the ‘90s the Council for the Defense of Human Rights and Freedoms, KMDLNj, gathered facts on the violence and crimes committed by Serbian police, some of which were even used to indict Yugoslav and Serb leaders in the ICTY in the Hague, 19 years after the war, despite spending millions of euros, Kosovo does not have an official record of war crimes.

While throughout the ‘90s 0.6 per cent of the budget was portioned out for research institutions, Kosovo after the war has never used 0.6 per cent of its yearly budget for research.

After liberation and the establishment of self-governing institutions, the governments in power started assigning a monetary value to every patriotic activity of the ‘90s in order to get votes from certain groups of people.

Source: Burimi: Mehmet Jarizi, Ismajl Kastrati, Bajram Shatri – “Këshilli Qendror për Financim në Kosovë”, Libri shkollor. | Illustration: Trembelat.

The poor state of Kosovo started with the politically imprisoned, paying them a certain amount for every night spent in prison. Then they started compensating former KLA fighters and their families. The 2018 Budget includes sums of compensation for the pensions of MPs in the ‘90s. Officials of the Kosovo government in exile also request compensation. In 2018, the government approved a draft law on the status of Albanian educational workers who worked between 1990 and 1999. This law stipulates an added pension for all teachers during the ‘90s, which will come from the state budget.

According to Minister of Finance Bedri Hamza, who opposed this law, the current draft leaves open the possibility to include workers in sectors other than education. Thus, the current content of the law may allow a minimum of 23,000 people who worked in the ‘90s to get pensions. All of these individuals have the right to a base pension of 263 up to 303 euros. If this law comes into power, 70 million euros from the Kosovo budget will go towards these categories. Add to it the 64 million euros that are used for KLA veteran pensions every year, the 10.5 million euros that go towards the politically imprisoned every year, the 300 thousand euros that go towards MPs who worked in the ‘90s, 38 million euros for the pensions of the wartime disabled, on average 200 million euros every year are utilized for these groups of people, or 9% of the budget.

If all of these people are entitled to receive pensions for their voluntary activism in the ‘90s, why can’t uncle Isa, who sold his cow to pay for the teachers’ salaries, or uncle Mustafa who gave 1,000 francs without even wanting his name to be known, or uncle Latif who donated over 10,000 DM for schools in Kosovo, and all the 282,000 people who contributed for financing the parallel state?

Sacrifice, voluntarism and the organization of Kosovar society during the ‘90s is one of the most successful arrangements that a society can achieve, and it continues to fascinate me to this day. Unfortunately, poor governance and corruption in the country of Kosovo, which is recognized by 114 UN members states, is drowning the the sacrifice and voluntarism by assigning them a monetary value. That being so, such actions, apart from the fact that they weaken our memory of the sacrifice for the parallel state in the ‘90s, are destroying the future of the independent country of Kosovo.

Featured image illustration: Trembelat for Prishtina Insight.

The opinions expressed in the opinion section are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BIRN.