Whistleblowers say lives are at risk from the scale of wrongdoing at Kosovo’s only international airport.

Bujar Ejupi has tired yet hawkish blue eyes beneath thick eyebrows. His skin is pale, his manner determined despite the threats and pressure of the past two years.

Ejupi, 37, was once deputy director and head of finances at Kosovo’s Air Navigation Service Agency, ANSA, the state body that manages air traffic at the country’s sole international airport run by a consortium between the private Turkish company Limak and Aeroports de Lyon since 2011.

Ejupi was fired in mid-2017, after a year in which he was repeatedly warned he would lose his job if he kept writing to the government about the negligence and mismanagement he had encountered.

He has spent most of the 12 months since trying to convince the police to take him seriously.

Ersen Shileku, the former head of operations at ANSA, faced a similar fate.

Now, after two years of Sisyphean effort to bring about change, the pair has gone public with allegations of nepotism, corruption and negligence that have led, among other things, to repeated power cuts and roadside repairs to a radar by a local car mechanic.

Air traffic control has effectively been handed to relatives of the man whose name Prishtina International Airport took in 2010, Adem Jashari – a revered guerrilla who was killed in 1998 along with 58 relatives in a hail of Serbian bullets as an armed rebellion against Serbian rule gathered pace.

Ejupi and Shileku have spent the last two years trying to raise the alarm about negligence and corruption at the Prishtina airport. | Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

Jobs have been handed out, Ejupi and Shileku say, to relatives of Kosovar politicians and to friends and family of senior managers, regardless of their qualifications. With more than 1.7 million passengers flying through the airport every year, they say lives are being put at risk.

“If something happens to flights and passengers, we would not be able to live with ourselves if we did not come forward and tell the public that the security and safety of flights is in jeopardy because of the deliberate negligence, lack of professionalism and the corruption that we saw,” Ejupi told BIRN.

The airport management disputes their accusations, some of which have also come to the attention of the European Union’s rule of law mission in Kosovo.

'Behind the glitzy façade…'

Kosovo’s only international airport is forever etched in history as the place where – as NATO soldiers took control of Kosovo from vanquished Serbian forces at the end of 11 weeks of air strikes – British general Michael Jackson rebuffed an order from the Western alliance’s US commander, Wesley Clark, to park helicopters on the runway to prevent Russian troops from reinforcing, telling him “Sir, I’m not going to start World War Three for you.” It was 1999.

Twelve years later, the airport became the object of newly-independent Kosovo’s first Public-Private Partnership, PPP, under which the Turkish-French consortium would run it for the next two decades on condition it invest 80 million euros in infrastructure upgrades, including construction of a new terminal. Limak holds 90 per cent of the shares in the consortium.

Kosovo’s government projected the deal would swell state coffers by 400 million euros over the course of the concession.

Three years later, the new terminal was inaugurated at a ceremony attended by Turkey’s then prime minister, now president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Kosovo’s then prime minister, now president, Hashim Thaci.

“But behind the glitzy façade of this big terminal, there are a lot of things in the PPP agreement that remain undone – things that are key to aviation standards,” said Ejupi.

Bujar Ejupi, head of finances at the Air Navigation Services Agency, ANSA, says he was shocked by the negligence and mismanagement in the agency. | Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

They include: widening the airfield for a runway safety strip at a cost of roughly 3 million euros; more space to park planes, valued at 5 million euros; a de-icing platform worth 2 million euros and a 1.5 million euro training area for firefighters.

Nor does the airport have a second backup power generator, a must-have for many businesses in Kosovo due to the country’s unstable electricity supply, let alone for its sole international airport.

“We had a power cut the day (then US vice president) Joe Biden was about to land in Kosovo,” on August 16, 2016, said Shileku. “I had just been appointed in the job as head of operations so it was my job to investigate why we had a cut.”

“The question totally backfired on me,” he said. “After a few exchanges my boss told me not to push it any further.”

Shileku’s boss was Bahri Nuredini, appointed as head of ANSA in 2011 by Thaci. ANSA is largely in charge of the Air Traffic Control Tower, while Limak manages the airport itself.

Nuredini’s uncle on his mother’s side is 43-year-old Bekim Jashari, the head of the ANSA board from 2008 until January 2016 when he left to become mayor of Skenderaj, the main town in Kosovo’s Drenica region, heartland of the guerrilla Kosovo Liberation Army that Thaci was a leader of.

Both Nuredini and Jashari were relatives of Adem Jashari, considered the KLA’s greatest martyr to the cause.

Ejupi estimates the failure to fulfill the contract has cost Kosovo roughly 14.5 million euros and that since 2011 the airport has made barely 30 million euros of the 400 million that the public purse was projected to reap over the 20-year concession.

“I started getting complaints from air traffic controllers that the tower was cold in the evenings and at nights when they had to operate flights,” said Ejupi. “This prompted me to check what was wrong with our heating system, only to find out it was never built by the Turkish company.”

Under the contract, Ejupi said, Limak “was obliged to build a tower with an independent heating and cooling system as well as a tower with continuous, 24/7 power supply – both of which we clearly did not have.”

Concerns raised elsewhere

Red flags have already been raised over the airport contract.

In two reports in 2014 and 2016, Kosovo’s National Audit Office warned about lax government oversight of the contract’s implementation.

The 2016 report complained that “the outstanding works are not finished yet and it is not specified when and how they will be finalised.”

Speaking to BIRN’s ‘Jeta ne Kosove’ program in April, Lorik Fejzullahu, the former head of the Private Public Partnership Unit within Kosovo’s finance ministry, said that Limak did not finish the works because it requires additional airfield space, which he said was occupied by KFOR, the NATO-led peacekeeping force stationed in Kosovo since 1999.

Limak could have walked away from the contract, he said, given the Kosovo government’s failure to secure the space needed from KFOR. “One day, sooner or later, Limak will have to do this remaining work,” said Fejzullahu.

KFOR, however, disputed this, saying it had received no such request to vacate airfield space.

“KFOR has not been involved directly in any planning or project for the improvement of Prishtina Airport facilities,” KFOR chief spokesperson Vincenzo Grasso told BIRN on July 11. “KFOR airport staff usually attend coordination meetings with Limak and sometimes those topics were mentioned, but KFOR was never blamed.”

“From what is visible on the ground and on the map, a possible extension of the runway and of the taxiway is not interfering with the part of the airport currently occupied by KFOR,” Grasso said.

Under the terms of the contract, the government has the right to fine Limak 10,000 euros per day for failure to complete the work. But it has yet to take this step, with Fejzullahu insisting “This is the best implemented contract in the region.”

Ejupi and Shileku say the delays are dangerous.

Ejupi first joined the airport staff in 2003 as an Aeronautical Information service supervisor, working up to the post of deputy commercial director before he left in 2013. He then joined Kosovo’s Riinvest Institute, authoring a 2015 report that detailed the shortcomings in the PPP deal and its implementation.

Shileku was the airport’s Coordination Manager from 2001 to 2014, when he became a Quality and Safety Manager at Istanbul Airport for the next two years.

Given the clear and obvious links between high level officials at the airport and political figures it is unlikely that any such investigation could be done without interference by individuals in positions of influence and power. EULEX report

When then Prime Minister Isa Mustafa appointed the pair to their ANSA posts in 2016, Ejupi believed the authorities were serious about putting things right.

BIRN has reviewed more than 30 letters and e-mails dating from August 2016 in which Ejupi and Shileku raised questions relating to the safety and security of flights and irregular activities regarding hiring, radar maintenance and suspicions of kick-backs paid to keep unfinished work under wraps.

They were sent, initially, to Mustafa, then Finance Minister Avdullah Hoti and then Transport Minister Lutfi Zharku. No one replied. Ejupi and Shileku repeated their complaints to the government of Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj that came to power in late 2017.

Asked about the concerns, Haradinaj told BIRN in December: “I am not a judge. The issues that they are reporting have to be investigated and dealt with by the courts.”

The whistleblowers have taken the matter to the police and prosecution and been interviewed. The police and the state prosecutor have told BIRN they are conducting a preliminary “collection of evidence” but no formal investigation has been launched almost a year since Ejupi and Shileku first complained.

A report by the EU’s rule of law mission in Kosovo, EULEX, expressed doubt about the effectiveness of any such investigation given the profile of those involved.

“[I]t is highly likely that there are serious safety issues, poor management practices and potential corruption taking place at the airport in Pristina that require further investigation,” said the report, written in late 2017 and leaked to BIRN early this year.

“Given the clear and obvious links between high level officials at the airport and political figures it is unlikely that any such investigation could be done without interference by individuals in positions of influence and power.”

A driver’s valuable ‘connections’

In a letter to Kosovo’s Anti-Corruption Agency, dated August 31, 2017, Ejupi detailed 10 separate practices at the airport that raised suspicions of corruption.

They included the promotion of employees to positions they were not qualified for, the mismanagement of assets and budgets, the payment of salaries for employees who never came to work and a mismanaged, 7-million-euro contract to relocate radar equipment and software.

Asked about hiring practices, Nuredini admitted to BIRN that around a dozen ANSA employees were relatives or friends of his and Bekim Jashari. He said he had in fact asked Limak to hire his brother as a baggage handler, which the company did in 2013.

“It’s true I asked a friend in Limak if he could do this for me, if he could hire my brother as a seasonal worker,” said Nuredini. “We’re not strangers; they showed understanding.”

The ANSA boss said other senior ANSA managers, past and present, had also helped relatives get hired at the airport.

BIRN’s investigation corroborated this. And one of those hires stands out.

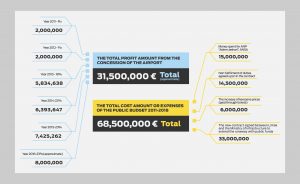

Projected costs and earnings from the Prishtina International Airport concession.

BIRN was leaked an invoice showing that a company called H&B ShpK is being paid 10,000 euros per month by Limak for consultancy services.

Until recently, H&B ShpK was owned by a Kosovar named Murat Mecini. Mecini also happens to be the personal driver of Bekim Jashari, in Jashari’s current position of Skenderaj mayor as well as when he was head of the ANSA board.

Mecini is also a member of the extended Jashari family.

Asked what kind of services the driver of a significant political figure might be providing, Limak Kosovo CEO Haldun Firat Kokturk told the Jeta ne Kosove program: “He is providing consultancy… We have seasonal workers for cleaning and security sometimes. He coordinates that and provides reports.”

When asked whether he was aware that personal drivers in Kosovo are frequently used as intermediaries for kick-backs, Kokturk replied: “It may smell like that to you…But… he is just the owner of the company. He has other workers working there.”

Mecini’s company, he said, “has connections” valuable for locating cleaners and security guards. BIRN asked for details regarding Mecini’s qualifications and the consultancy contract, but Limak declined to provide them.

During the course of this investigation, on February 14 this year, Mecini re-registered ownership of H&B to Ilker Yesilmenderes, a Turkish national. Kosovo’s business registry is a public record and names Mecini as owner of H&B ShpK from 2013 until Yesilmenderes took over.

Contacted by phone, Mecini told BIRN “my contracts are none of your concern.” Jashari did not respond to requests for comment.

According to BIRN’s findings, Limak’s employees include President Thaci’s nephew, Sinan Thaci, and the son of former Foreign Minister Skender Hyseni, Yll.

According to BIRN’s findings, Limak’s employees also include President Thaci’s nephew, Sinan Thaci, and the son of former Foreign Minister Skender Hyseni, Yll. Kadrie Buja, whose husband Shukri Buja was mayor of Lipjan – the municipality where the airport is located – was also on the books until her husbands’s tenure ended in 2013 and she was let go (Limak refused to comment these employments).

Ejupi and Shileku allege that such practices represent serious conflicts of interest and are unlikely to encourage strict monitoring of how well the PPP contract is being implemented.

Kokturk denied Limak hired staff based on their political connections.

“In this country, with a very small population, 1.7 million, everyone needs a job,” he said. “The one who asks for a job, it is not something to be ashamed of. It is good to ask for a job,” he said. It shows, he argued, that those in power are not asking for money or gifts.” They are “just willing to work.”

Case ‘closed’

Ejupi cited the example of the non-existent second generator. Its absence was first noted in an ANSA inspection in 2014, two years before the power cuts began and before Ejupi joined the company.

“That inspection report was commissioned specially in order to identify what outstanding work Limak needed to finish,” he said.

According to copies seen by BIRN, a draft of the report from February 2014 notes the absence of a second generator. The final version, however, produced in September, describes the matter as “closed”, without elaborating.

Two years later, in August 2016, the lights went out three hours before Biden was due to land, a major political event in Kosovo where the United States enjoys significant clout and popularity as a major financial and diplomatic backer.

Shileku frantically started investigating. Driton Mehaj, head of the technical team, told him ANSA relied on a manual generator owned by Limak, which has to be powered up and takes several minutes to get going. Limak’s Kokturk also pointed to this generator as the backup power Limak was obliged to buy for ANSA.

“This worried me to death,” Shileku told BIRN. “Minutes in aviation are not something you should take lightly.”

Driton Gjonbalaj, head of Kosovo’s Civilian Aviation Authority, CAA, told Jeta ne Kosove in early 2018 that blackouts are common in the industry, citing recent power cuts in the US city of Atlanta and in Croatia. The CAA has certified ANSA as fit for service despite the lack of a second generator.

Nuredini also played down the danger, saying the main generator was up and running again within 24 minutes.

Only it happened again less than a year later, on June 27, 2017, when the power went and the UPS – an uninterruptible power supply that should kick in temporarily while power is restored – also failed. Planes disappeared from the screens of air traffic controllers and Skopje airport had to jump in until the power came back 12 minutes later, according to multiple accounts.

“When it happened the first time, and we lost power for 30 minutes, I found it unacceptable for us to rely on this sort of power supply,” Shileku said.

“It costs only 20,000 euros to have this equipment and even if the private investor wanted to cut corners and not invest in this, I am sure we could have gotten it if we had insisted on it.”

“I told my colleagues that even supermarkets in Kosovo buy a backup generator to look after their meat in the freezer and here we are dealing with people’s lives in the air.”

Car mechanic-turned-radar repair man

Nagip Goga, a welder and car mechanic in the town of Ferizaj south of the capital, recalled the day airport staff turned up and asked for his help. It was December 30, 2016, one of the busiest periods for the airport.

“They brought this rotary joint into my workshop and said it was urgent,” he told BIRN. “I weld it to the required size and when they tested it they said it worked.”

Little did Goga know but the joint was part of the airport’s navigation radar, which had broken down. A 7-million-euro contract between ANSA and the equipment supplier TCN for maintenance of the radar had been terminated by TCN three months earlier over late payments by ANSA, according to documents reviewed by BIRN.

With no maintenance cover and no spare parts in storage, ANSA called neighbouring airports to see if it could borrow a spare rotary joint. Tirana agreed and a number of ANSA workers were dispatched to pick it up. It turned out the spare did not fit Prishtina’s radar, hence Goga the welder’s bit-part in restoring operations.

After a power cut at the airport, Ersen Shileku, head of operations at ANSA, asked for a risk assessment. It was never done. | Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

Shileku said the episode was eye-opening.

“For anybody that produces radars it is unacceptable to have spare parts be modified by anyone not authorised to work on such sensitive equipment,” he said.

Gjonbalaj of the CAA, however, was unperturbed, saying an authorised ANSA engineer supervised Goga’s work, meaning flight safety was never in jeopardy.

“The CAA guarantees that the services [navigating signal] offered by that radar are in accordance with all safety standards,” he said.

The CAA’s own website, however, bases safety and risk assessment standards on European Commission regulation 1035/20011, according to which providers of air traffic services must ensure that sub-contractors “have and maintain sufficient knowledge and understanding of the services they are supporting”.

Goga was reluctant to offer any guarantees for his work.

“Of course, I’m no aviation expert, nor have I ever worked on navigation equipment before so I’m not qualified to offer any guarantees on this part,” he said.

The episode epitomised the airport’s failure to invest in expertise, Ejupi said.

“You have to ensure that the people dealing with the navigation equipment are professionals, and more importantly that we have the procedures in place to respond professionally once this equipment breaks down,” he said.

Such measures, he said, “can end up saving lives.”

Two air-traffic controllers at the airport, who spoke on condition of anonymity given their continued employment at ANSA, complained that they were working on sub-standard software because the contract with the radar supplier, TCN, had ended before the hardware had been integrated. That has left them working on a different signal to their counterparts at other airports in the Balkans.

Asked about the oversight, Nuredini said the work would be completed with extra funds in 2018.

Nuredini fired Ejupi on August 14, 2017; the Kosovo government confirmed his dismissal in January 2018.

Ejupi said he refused to leave without a written explanation for his dismissal, so Nuredini called security.

The ANSA boss denies having Ejupi thrown out by security but did say he was fired for “having poked his fingers into contracts, as it’s not his job to inspect things.”

Ejupi was replaced as ANSA deputy director in June this year by Shpetim Selmanaj, a member of Prime Minister Haradinaj’s co-ruling AAK party. Selmanaj was secretary of the AAK youth forum, a personal assistant to Haradinaj and has overseen river cleaning projects (he admitted to being an AAK member but did not comment further on his recruitment).

Ejupi applied for his old job when it was advertised, but did not hear back. “Clearly, politicians would rather not see professionals running things, but society does,” he said.

“In aviation, one cannot wait for things to go wrong and only then mobilise to fix them,” he said. “It will be too late to fix things once they go wrong.”

Design by Jeta Dobranja, Trembelat. Development by Faton Selishta and Lend Kelmendi, Kutia. Graphics by Bardh Ulaj, Trembelat. Photography by Atdhe Mulla. Videography by Fatrion Ibrahimi.