A relationship between a Bavarian campsite owner and a Kosovo Albanian family persists over two generations of migration.

Driving by car from Munich to Krün, a village close to Germany’s highest mountain, the Zugspitze, makes it impossible to miss the countless snow-covered Bavarian houses. Long wooden balconies and ornamental paintings featuring Christian and/or Bavarian symbols decorate the small houses. Shopkeepers of these villages greet their clients with “Grüß Gott!” (“may God greet you!”). Bavarian, the German dialect of this region, can often sound gruff, even when used among acquaintances and friends.

The traditional buildings are indicative of those who dwell in them: Krün’s inhabitants are not considered particularly progressive: in the past 60 years, voters have consistently elected a man from the conservative Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) as their prime minister.

The traditional buildings are indicative of those who dwell in them: Krün’s inhabitants are not considered particularly progressive: in the past 60 years, voters have consistently elected a man from the conservative Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) as their prime minister.

One of these Bavarians is the 79 year-old Armin Zick, who lives in Krün and owns the Alpen-Caravanpark Tennsee, a five-star campsite. Since its foundation in 1953, the luxurious campground has been distinguished 19 times – including awards from France and Germany. Zick could be one of these distant, religious and conservative Bavarians. What one immediately notices upon seeing Zick, who is always wearing Bavarian traditional costume, is that he is not gruff at all. If one were not to know that the people to whom he is chatting are not his clients, one could think they are his friends; he has kind words for each of them, and their mutual affection seems genuine.

One of the men he speaks with is Shefki Hajdini, a 60 year-old man from the Kosovo village of Komoran, nestled deep in the Drenica valley. At the restaurant of the Alpen-Caravanpark Tennsee he began to speak in Albanian, his mother tongue.

“Listen: in 1993, there were three Kosovo-Albanians working here as caretakers: Rrahim Kluna, Latif Berisha, and I.” Hajdini left Kosovo in 1993 because of the unstable political and economic situation and has been living in this region since then.

The first generation of Kosovar migrants went as Yugoslavs to Germany after Yugoslavia and Germany signed a Gastarbeiter (guest worker) treaty in 1968. Many Kosovars, who lived in the least developed part of Yugoslavia, went to Germany in search of work. In the 80s, finding a job in Kosovo was especially difficult for Albanians, who were discriminated against by the Serbian public institutions in Kosovo.

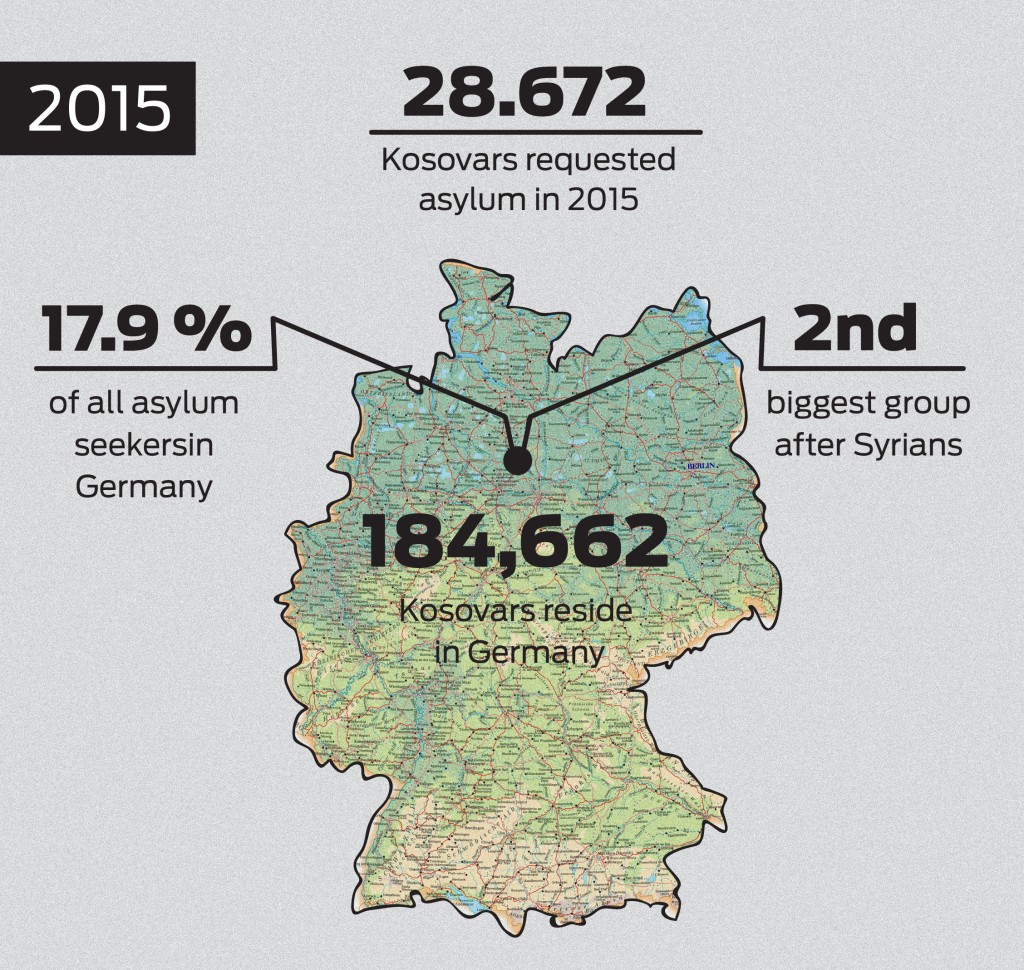

Mr. Kluna, Mr. Berisha and Mr. Hajdini migrated in 1991 as part of the second Kosovar wave to Germany that intensified when Yugoslavia collapsed into war. A third post-war wave is ongoing. 28.672 Kosovars requested asylum in 2015 – 17,9 per cent of all asylum seekers in Germany– making them the second biggest group after Syrians. According to a census in 2014, 184,662 Kosovars reside in Germany, a number that does not include the Kosovars who have acquired German citizenship.

But not everyone gets to stay. Amongst his former colleagues at the campsite, only Hajdini was allowed to do so. In 2000, after the war in Kosovo ended, the German state deported the Kluna and the Berisha family back to Kosovo.

CIKI

Six months after the Klunas and the Berishas left Germany, Hajdini updated Zick on their situation. The Berishas managed to create a decent life, but things for the Klunas did not go as well. The family matriarch was – and still is – suffering from a serious psychological disorder, which cannot adequately be treated in Kosovo. Their home in Drenas was destroyed during the war and Rrahim Kluna had no work.

“I told Zick that I am going soon to Kosovo and will give the Klunas 1000 euros, because they really need help,” Hajdini said, pronouncing Zick the Albanian way: Ciki (“tseekee, with emphasis on the first “ee”). Without hesitation, Zick gave Hajdini 2000 euros for the Klunas as well. From then on, the campsite owner sends them up to 3000 euros annually in order to help the family.

“I found it unfair that the Klunas had to leave Germany. Sani Kluna, Rrahim’s wife, had no therapy in Kosovo,” Zick explains, as he take a seat next to Hajdini.

THE SECOND GENERATION GASTARBEITER

Just then a young man joins us. This is Besmir Kluna, Rrahim’s 22-year-old son. Besmir started his apprenticeship as a cook at Alpen-Caravanpark Tennsee last November, which is little short of a miracle.

Together with two friends, Besmir Kluna left his family in Kosovo at the end of February 2015, and arrived in Germany five days later, where the German police caught him in Passau.

Together with two friends, the young man left his family in Kosovo at the end of February 2015, and arrived in Germany five days later, where the German police caught him in Passau, a city in south-eastern Bavaria bordering Austria. Like Besmir, approximately 50.000 to 100.000 Kosovars left for Western Europe in the beginning of 2015 seeking asylum and jobs.

Before his family was deported in 2000, Besmir went to kindergarten in Germany. Back in Kosovo, he improved his German by watching his favorite show Knight Rider on the German television channel RTL. The young man earned the money for his flight by working for a call centre in Kosovo’s capital Prishtina, where he replied to the complaints of German clients about Italian kitchen products.

“It was not even possible to find an apprenticeship in Kosovo,” he said. Life in Kosovo was “very difficult, especially the first years,” he says crossing his arms and his head hanging.

A LONG WAY TO KRUN

The police sent Besmir to Munich, where he did not stay long. The foreigner registration office organized him a bed at an asylum seekers’ hostel in Bramsche, a small town in Lower Saxony. Having informed his family where he was staying, Besmir’s father then wrote his former boss Zick an SMS, telling him the whereabouts of his son.

On March 23, 2015, Zick traveled the nearly 800 kilometres between Krün and Brahmsche to see Besmir Kluna, whom he remembered as a little boy jumping in the bouncy castle of his camping ground. “We liked each other immediately,” said Zick, and Besmir approvingly nods several times, grins, and slaps his employer on the shoulder. Zick was impressed by the young Kosovar’s German and his determination to find work.

On March 23, 2015, Zick traveled the nearly 800 kilometres between Krün and Brahmsche to see Besmir Kluna, whom he remembered as a little boy jumping in the bouncy castle of his camping ground. “We liked each other immediately,” said Zick, and Besmir approvingly nods several times, grins, and slaps his employer on the shoulder. Zick was impressed by the young Kosovar’s German and his determination to find work.

In Brahmsche, the Bavarian explained Besmir his options: either voluntarily go back to Kosovo or be deported, which meant losing the right to enter Germany for several years. Zick offered to do anything he could to hire the young man as an apprentice cook but that would mean Besmir had to first go back to Kosovo. He left voluntarily.

“One month later, Zick had organized everything, and I could come back to Germany,” says Besmir, grinning.

WORK FORCE NEEDED

“The day I met Zick for the first time after fifteen years was the most beautiful day in my life,” says Besmir.

Germany lacks qualified labour for highly-skilled jobs such as doctors, but also lacks workers for menial tasks like apprentice cooks. According to the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DIHK), 17,974 people started an apprenticeship as cooks in 2006 while in 2013, only 9,750 did so – a decline of nearly 50 per cent. With this knowledge, Armin Zick went to the employment agency in Garmisch-Partenkirchen to run a Europe-wide advertisement for a cook at his camping ground.

When the employment agency official told Zick that nobody replied to his call, he said: “This is really a pity, but I have a potential cook: look!” He then pulled his Samsung smartphone from his pocket, and showed him the picture of him and Besmir. The bureaucratic obstacles in Germany – health insurance, registration of Besmir’s apprenticeship to the responsible institution, etc. – were numerous, but not insurmountable. The Kosovar bureaucratic hurdles demanded more endurance: Zick sent letters to the German embassy in Prishtina three times, but never received a reply; e-mail worked better.

OPTIMISM AGAINST ALL ODDS

Last October, Hajdini and Zick drove to the Munich Airport, where they picked up Besmir. The young man lives now in a room in the campsite’s main building. After attending a vocational school, he has started cooking at the Alpen-Caravanpark Tennsee.

As a child, Zick was confronted with the destitution and hardship suffered by refugees. He was eight years old when World War II ended. One year later, two German refugees – the couple Schlichtig – moved into the flat where he was living. Later when he began his apprenticeship as confectioner in Hanover in 1955, he alsp rented a room from a family who had fled during the war, understanding their travails even more.

In 1957, Zick moved to Stockholm, where he worked as pastry cook for at the Hotel Ambassadör. He traveled through Scandinavia and after he saved some money, he moved to Oslo.

“In Oslo, it was either ‘German bastards’ or ‘German friends.' In Scandinavia, I learnt to prevail against opposition,” Zick says, revealing his life motto, “laugh more, shine more, say yes to life.”

“In Oslo, it was either ‘German bastards’ or ‘German friends,’” he remembers. He was hired at a cake shop but his colleagues refused to work with him because of his nationality. Not the type to be discouraged, he found a job as gardener. “In Scandinavia, I learnt to prevail against opposition,” he says, revealing that his life motto is “laugh more, shine more, say yes to life.”

Zick says his personal experience as a migrant worker was what motivated him to help the Kluna family for fifteen years, and later hire Besmir.

Tolerance toward migrants is the defining issue in contemporary German society, he believes. His country is the primary destination sought by many migrants coming to Europe and their acceptance, he says, primarily depends on the empathy one can feel for them.

Shefki Hajdini, who also plays a crucial role in facilitating the communication between Zick and the Klunas, highlighted that Zick was always a very caring employer. “He always asked about our families, and never put obstacles in our way,” Hajdini says.

In Germany, the Kosovar can do what he cannot do in his home country: work. And the gratitude for this is obvious.

“I enjoy my work a lot here,” says Besmir, high fiving his boss. He too dreams of traveling the world and perhaps after his apprenticeship in Krün he will be able to do that.“The good thing about my apprenticeship is that I can work all over the world. Food specialities also are a good way to discover new cultures,” he concludes with a smile.