On January 19, an exhibition showcasing the work of 15 Western Balkan artists opened in New York at the Austrian Cultural Forum, with a panel discussing the concept of normality. Our correspondent reports on the affair.

There’s nothing normal about how I got to cover the Normalities exhibition in New York City. In a sense this story began with a disruption in my normality. My busy winter break schedule of video-games, binge-watching Netflix, and reading was interrupted by the invitation to cover the exhibition for Prishtina Insight. And so, after a brief period of reluctance (for all heroes go through such a step) and upon conquering my fears (of being unworthy of covering an art show), I mustered the courage to battle the infamous Manhattan freezing winds and haul my winter laziness to Austrian Cultural Forum at 52nd street (between Madison and Fifth Ave).

The opening night of the Normalities exhibition consisted of a panel discussion followed by the opening reception featuring works from fifteen artists: Cäcilia Brown (France), Nemanja Cvijanović (Croatia), Dušica Dražić (Serbia), Flaka Haliti (Kosovo), Ibro Hasanović (Bosnia), Jelena Jureša (from Novi Sad, Yugoslavia), Jakob Lena Knebl (Austria), Irena Lagator Pejović (Montenegro), Armando Lulaj (Albania), Alban Muja (Kosovo), Damir Očko (Croatia), Ana Prvački (Serbia), Maruša Sagadin (Slovenia), Sašo Stanojkoviќ (Macedonia ), Kerstin Von Gabain (USA).

), Kerstin Von Gabain (USA).

The exhibition strives to explore the concept of normality. It questions what it means to be an artist in a region like Balkans, which has been in transition for about a quarter of a century. It also investigates ways of dealing with individual and collective identity in a state of such flux. During the panel discussion on the exhibition’s opening night, the Macedonian curator Suzana Milevska claimed that the term “normalization” was itself problematic since it made sense only within a particular time-frame because of the way norms are established—meaning that with the passing of enough time, what was once considered as an exception to the norm, comes to be regarded as normal.

With a drink in hand I elbowed my way through a Subway-like crowd under the tunes of a live performance of music from Former Yugoslavia. As the two normalities mixed (NYC’s tight spaces and the feeling of being in a Balkan marketplace), I missed only the smell of grilled pljeskavicas for the illusion to be complete.

Nevertheless, it was possible to view and enjoy some good art. Armando Lulaj’s video Never explores normality by manipulating history. Lulaj rearranges Albanian dictator’s name, Enver, written on a side of a mountain, into Never, by switching around the letters. In this way, what used to be the symbol of normality for fifty years, is disrupted by this artistic manipulation. This got me to think that perhaps this is the reverse of what the Macedonian curator Suzana Milevska talked about.

In Film Marathon Macedonian artist Sašo Stanojkoviќ focuses on the institution of the cinema. His video-projected still image of an audience watching a cinema screen is a lament for the vanishing of cinemas in Skopje. Instead of being a celebration of a new normality, one could argue, Mr. Stanojkoviќ’s work it’s a requiem for a vanishing one.

Nemanja Cvijanović’s piece was impossible to miss due to its sheer size but also for being a tribute to Gustav Klimt, busy with images of what I would call a melting pot of Balkan normalities. Jelena Jureša’s film piece entitled Mozarts treats the issues of identity under new normalities, in this case following Eastern Europeans wearing Mozart costumes and selling concert tickets in streets of Vienna.

For Alban Muja, on the other hand, Kosovo’s current quest for normality is tightly linked to isolation and ghetto-like life imposed by strict visa regimes. During the panel he wondered if the normal state of being in Kosovo was that of crisis. In his work My Name, Your City, Muja evokes Albania’s isolationist past, during which Albanians were not free to move. This inaccessibility to the homeland could be traced in the longing of many Kosovars during 70s and 80s, which resulted in a generation of children named after geographic locations in Albania.

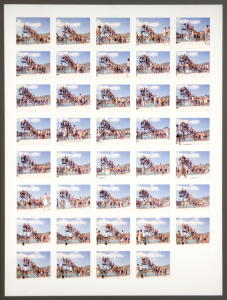

Mr. Muja’s My Name, Your City consists of a series of photographs, in each of them the person bearing the name of a city in Albania poses holding an enlarged print of the eponymous city. So Saranda holds a picture of the Albanian coastal town, Berat that of the UNESCO protected site, and Milot that of a hamlet in northern Albania that is unremarkable in both scenery and history. When viewing these pieces, I was reminded of an excerpt in Plato’s Symposium. There Aristophanes describes love as the search for one’s other half in order to achieve a state of normality. Perhaps in Muja’s work there is also a quest for his subjects to be joined with their corresponding other half, which in this case are not in the form of another person, but that of a city or a town.

Speaking of cities, Maruša Sagadin’s works presented at this exhibition used the city as a starting point for her creative process. To an untrained eye her work could look much like the seven year old niece’s first attempt at playing with chunks of wood, Styrofoam and cement, putting them together haphazardly. But in this case it is the process and the thinking that went into creating the work that really matters. For her installations she used materials found around Manhattan construction sites. In this way she explores her surroundings from a spatial point of view, and not a geopolitical once, since, according to Sagadin, Slovenia always refused to identify with the Balkans. This got me thinking about the power of labels, or lack thereof, and to ponder the good old Shakespearean question, “What’s in a name?” realizing that normalities could be set through nomenclature, like in Mr. Muja’s artwork.

Flaka Haliti’s work, entitled Chain Reaction, consists of a series of photographs representing a different time frame.The photos form a scene where a long line of young boys on a platform wait to jump into a swimming pool. Its title reminded me of subatomic particles and nuclear physics. Perhaps normality doesn’t have a clear start and an end, and is a chain reaction of inseparable continuous events. This eventually led me to thinking about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, and that normality, or lack thereof, might depend whether the observer is inside or outside of the (relativistic) frame. But before merging the theory of relativity with Milevska’s abovementioned argument, it didn’t take long to realize I was slipping into the risky territory of making things up, especially since the formal interpretation of Chain Reaction had to do with the normality as it relates to male bonding, in this case as the boys wait to jump into the pool.

In the end, I recognized the challenge of writing about works of fifteen plus artists. Accepting the impossibility of doing justice to each of them, I left the room to move on to my own normality. Battling yet again the fierce Manhattan wind to the closest Subway station that would get me home, I didn’t fail to notice the coincidental mirroring between life and art: just as the exhibition exploring normality was opened in New York, an ocean away, “normalization” talks between Kosovo and Serbia were happening in Brussels. Striving for normality has become the norm it seems, both in art and in life.