New York-based artist talks to Prishtina Insight about representing Kosovo in the prestigious Venice Biennale art show this year.

For Peja-born artist Sislej Xhafa, “art is an emergency.” The role of art in society, his mantra goes, is to raise questions about “human elements in inhumane conditions.”

This May, Kosovo will take part in the 57th Venice Biennale international art show for the third time represented by Xhafa and his exhibition Lost and Found. Based in New York, Xhafa is one of Kosovo’s most renowned contemporary artists working today. Though his art has not yet been exhibited in his home country, personal experiences regarding immigration, legal status, and freedom color his works.

Keeping an air of mystery and without describing his upcoming exhibition in detail, Xhafa conversed with Prishtina Insight to talk about the themes he explores in this major exhibition. Viewers should expect Xhafa’s Kosovo Pavilion to continue raising questions around freedom and justice. Though the exhibition will not be revealed until the Biennale’s opening, Xhafa’s overall oeuvre might hint at what the artist intends to present.

“With Lost and Found I want to highlight human dignity, justice, and transparency towards the processes of injustice. Lost and Found is about interaction, silence, and presence. Lost and Found is about living memory and about challenge,” he said on a recent Skype call from his studio.

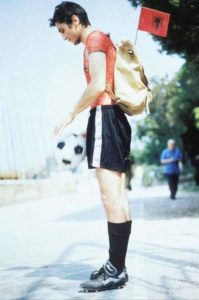

Xhafa represented Albania as a clandestine in Venice Biennale in 1997. | Photo: Kosovo Pavilion Facebook

This is not the first nation that Xhafa will represent in Venice. He has officially taken part in Italian pavilions, including in the 2013 showcase of Italian artists, and has unofficially represented Albania. In 1997, at the outset of his career, he snuck into the Biennale grounds dressed as an Albanian soccer player, blaring an Albania-Italy match from a radio attached to his shoulders. He titled his performance Albanian Clandestine Pavilion in an attempt to comment and stage an ‘intervention’ on Albania’s absence from that year’s show.

“I wanted to highlight the complexity of exclusion and inclusion in the Venice Biennale,” he explained, emphasizing the national prestige that countries seek from this contemporary art event. “Since Albanians and Kosovars are part of the global project of emigration, I wanted this performance to be live, to be a mobile architecture.”

An immigrant who lived first in Italy and then the United States, he is most known for his exploration of legality and illegality, migration, and the politics of representation.

In 2001 at the Istanbul Biennale, Xhafa’s performance Elegant Sick Bus highlighted what he has called the “forced hospitality” and touristic gaze inflicted by the tourist economy. Several men pushed a seemingly broken-down, mirror-plated bus down bustling Istanbul streets. With the bus’s reflective surface, Xhafa wanted to implicate the audience, including the local population, in the spectacle.

Sislej Xhafa, Elegant Sick Bus, 2001/2006. | Photo: Yvon Lambert Gallery

In juxtaposition to this earlier statement on tourism, two more recent works, Barka (2011) and Medusa Archive (2014), focus on forced migration. They are somber works, using found objects to highlight the refugee crisis.

Barka is a boat constructed from hundreds of shoes found on the Italian island of Lampedusa, a transit point for thousands of asylum seekers attempting to cross the Mediterranean. Medusa Archive, an appropriation of objects found on the island, was an elegy to the 2013 Lampedusa shipwreck.

Xhafa does not want to produce sensational art: he did not want to show explicit imagery of violence experienced by refugees such as what is “shown on BCC and CNN,” he said. His comments are reminiscent of a larger question about the effects of war photography and depictions of violence, raised for example in Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others. Sontag argues that images of war often agitate, reiterate, simplify and “create the illusion of consensus”–the illusion that when we see horrific images of human suffering, ‘we’ innately feel empathy. Yet, the late author argued, no such ‘we’ should be taken for granted.

Sislej Xhafa, Barka, 2011. | Photo: Collection Nomas Foundation, Rome, Courtesy GALLERIA CONTINUA, San Gimignano / Beijing / Le Moulin, Photo: Amedeo Benestante

For Xhafa art is about experience and questioning. The role of art is to help viewers experience “different dimensions,” he explained, to open a more contemplative state and alter one’s own state of mind yet raise universal questions.

Critics often point out that Xhafa’s work raises questions, but does not provide technical answers.

“If I already knew the solutions, I would never do art. I use art as a question. We live in a very dynamic, global world. Geographical relations, immigration, injustices… they affect our everyday lives… there is no one solution, there are thousands of solutions,” he responded. “We have to use creativity, not only in art, but in every field… creativity is essential to our survival.”

Sislej Xhafa. lost and found (detail). 2017. | Photo: Courtesy GALLERIA CONTINUA, San Gimignano / Beijing / Les Moulins / Habana

photo: Berin Hasi, Republic of Kosovo Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale

Survival and hope have been central themes weaved throughout Xhafa’s artistic career, and we should expect to see these themes tied to his birthplace as he represents Kosovo in Venice this year. The national pavilions, each with their own curators and artists, are typically managed by states’ ministries of culture. To Xhafa, navigating his own politics of representation is a welcomed part of the challenge.

“The Biennale does not so much represent an artistic statement but a political statement–unfortunately, a national political statement. I am kind of disturbed by that. However, I accept this as part of the challenge,” he said.

“In the end, the role of art is to make good art, without too much talk.”

Lost and Found is curated by Arta Agani, Director of the National Gallery of Kosovo, in collaboration with Kosovo’s Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports. It will be on view in Venice from May 13 – November 22, 2017 (with a Professional Preview on May 10, 11 and 12.)