Centuries ago, tattooing was celebrated as the highest of art forms in the Balkans. As the years went by, the practice was vilified – reserved for gangs, criminals and soldiers alone. Today, practitioners of tattooing in Kosovo explain body art’s revival and its newfound monumental popularity.

Rewind to 1978: 21-year-old Faruk Gashi is serving as a military officer after being conscripted into the Yugoslav National Army, JNA. He is stationed in Ohrid, a southwestern city in North Macedonia. Feeling reckless, and surrounded by friends egging him on, Gashi reluctantly offers his forearm to another officer, who is armed with nothing but a needle and ink.

Soon after, he opens his eyes, looking down to see the letters JNA tattooed crudely across the very middle of his forearm, along with OHRID and the date, 15.06.78.

Today, 41 years later, Gashi brandishes his forearm across the table, the tattoo now so faded the letters are almost impossible to discern. Although he regrets his decision, he shrugs off the feeling. “All my friends back then had tattoos, snakes, naked women… people were doing them for free with a needle. I tried to rub it off immediately but nothing worked,” he said, laughing.

It was not always a laughing matter for him, though. He could never let his father, an imam, see the tattoo, and people told Gashi he would not be able to have a proper burial now that he had ink on his skin. A decade later, in 1988, he was desperate to remove this mark of military affiliation and traveled to Nis, Serbia, to a doctor that he heard could remove it.

“The doctor said that the only way to remove it was to cover the tattoo with a skin graft from down there,” he said, sheepishly pointing to his behind. “There’s no way I could have done that.”

The recent history of tattooing in the Balkans has been intrinsically tied to conflict, from the controversial legacy of Yugoslav army tattoos in the early 20th century and Serb police demanding tattoos for free from Albanian artists during the 1990s, to the presence of NATO soldiers in the early 2000s, who played a crucial role in keeping the tattoo industry in Kosovo alive.

However, as societal mindsets and Kosovo’s cultural and economic landscape is changing, a new generation of contemporary tattoo artists are transforming the industry and shifting it away from its complicated legacy.

Traditional tattooing practices in the Balkans

Across the Balkans, the tradition of using body art began long before Gashi and his friends were messing around with needles and ink. According to Lars Krutak, an anthropologist specializing in body art, the origins of tattoos in the Balkan region can be linked back to women that followed the Catholic religion, or perhaps even earlier in history.

“It is not known when or where the practice of tattooing originated among the Catholics of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, or even the Vlachs of southern Albania and northern Greece,” he said.

Krutak recalled anthropologists from the 20th century noting how tattooing in Albania and the surrounding region was tied not to the Catholic religion, but “a number of curious pagan beliefs” related to darkness, light and other holy powers not directly in line with traditional notions of Christianity.

According to Krutak, anthropologists Ciro Truhelka and Mario Petric were skeptical of the Catholic origin of the tattoos. Writing in the late 20th century, Truhelka and Petric said that the designs discovered on people’s skin in the last few centuries — combinations of cruciforms, celestial bodies, and other natural symbols like the moon, sun and plants — long predate Christianity.

Krutak said that body art in the Balkans were made from the “soot of resinous pinesap, which would be collected on a plate and then combined with honey, water, saliva, and mother’s milk from women who had a male child with blue eyes.” Other substances were also incorporated to form the ink, including milk from a black sheep, horse milk, an egg yolk, the juice of juniper berries, holy water and sugar.

Both the tattoo artists and the equipment they used were far removed from modern tattoo studios. “The traditional tattoo patterns were applied by old women, who first stenciled the design onto the skin with the blunt end of their tattooing needle or a chicken feather,” Krutak explained. “Sometimes the design was carved into a piece of willow or ash bark, and stamped onto the epidermis.”

These practices are rapidly vanishing in the Balkans, said Krutak, because women who continue to follow this tradition are now very elderly. Krutak spent a number of years in the Balkans in the early 2000s, discovering more about the traditions of tattooing. “When I was in northern Greece in 2002, I found just two Vlach women with tattoos – both were more than 90 years of age,” he said.

Soldiers, gangs & intimidation

Krutak has been spending time in the Balkans since 1998, first in Bosnia and Herzegovina and then living in Kosovo at various periods between 2000 and 2002, residing in Suhareka, Dragash and Mitrovica while working for the OSCE.

On the hunt for artists working in Kosovo in 2001, Krutak’s research led him to a man named Naki Krasniqi in Prizren. “I visited Prishtina quite frequently for meetings, but I could not track down any artists there at the time. I had heard about one Prishtina artist that Naki was helping to train and another who left for Germany, but Naki seemed to be the only tattoo artist working in the country,” he said.

“I was struck by how much adversity he had faced during the war: Russian mercenaries and Serbian soldiers forced him to tattoo them for free, and if he didn’t they threatened to kill him and his family,” Krutak continued. “Eventually, Naki and his family fled to Albania until the war was over.”

When Naki returned from Albania his shop had been destroyed, but the artist’s passion for the art led him to rebuild it, eventually giving Krutak himself a big tattoo on his left arm.

Enes Baxhaku, a tattoo artist from Prizren with studios in his hometown and in Prishtina. | Photo: Atdhe Mulla.

Naki was not the only tattoo artist that faced problems in the ‘90s. Enes Baxhaku, a tattoo artist from Prizren with studios in his hometown and in Prishtina, recalled shutting down his first studio during the war.

“I was working since about 1994, but just doing handmade, amateur tattooing,” he said. “Back then, my main customers were gang members, people who wanted this kind of prison-style tattoo.”

It was only after the war that Baxhaku started designing and tattooing professionally. Once NATO troops came in to the country, this opened the door for proper equipment to enter too. In the early 2000s, he said, tattoos still were not incredibly popular, both because of religion and the association of Baxhaku’s style of tattooing and designs with criminality.

Once he began working in Prishtina in 2004, almost all of his clients were members of the KFOR troops stationed in Kosovo. “KFOR troops, internationals, and my biker gang, Black Eagle. We have 89 members, they are my brothers,” he said, grateful that they were interested in his favorite style of tattooing – black, grey and satanic.

Their business kept him afloat until tattooing became more popular among mainstream society. Now, Baxhaku has the studio of his dreams. Named after his biker gang, his Black Eagle studio in Prizren is kitted out with enough stations for his growing list of apprentices, and his collection of classic motorcycles takes pride of place in the studio itself.

The industry blossoms

The tattoo industry has grown exponentially since the war ended, and Baxhaku is not the only one who has seen success since then. Sulejman Fani and Betim Kadriu opened their small studio, Heavy Ink, in February. According to them, the clientele has changed dramatically since Baxhaku and Naki were working in Prizren.

“Tattoos used to be for people who were in jail or in the military, this is where the trend started here,” said Kadriu. “There are tattoo artists here who owe a lot of their success to the NATO soldiers stationed in Prishtina.”

Now, he says, the industry is at the top of its game. “Tattoos aren’t really taboo anymore, you don’t have to be a thug to get them. You see people in famous bands or in movies that have them, it’s just not such a big deal anymore.”

Alaudin Murturi, who runs Prishtina Ink Tattoo, agrees. But according to him, the tattoo industry is still almost exclusively imported, with equipment, training and even the majority of customers all coming to Kosovo from abroad. “Almost all of my clients now are from the diaspora, people from Germany and Switzerland,” he said.

In order for Murturi to learn how to start tattooing and find the right equipment, he had to move to Luxembourg, and work for free in a tattoo studio, cleaning, changing needles and slowly learning how to do stencils, sketches and small designs. After six months, he said, the owner of the studio gave him two machines for free.

Before he got his hands on a machine, Murturi resorted to more drastic measures to fuel his desire to be a tattoo artist.

“I was born knowing this was what I wanted to do. I remember being ten years old and going up to any stranger I could find to ask them about their tattoos,” he said. “I tattooed myself and two or three of my friends during high school, stick-’n-poke style, then hand-built my own electric motor to make the machine by breaking up an old radio and using the parts. It was stupid and dangerous, but my friends are still alive, and they still love the terrible tattoos I gave them.”

Before becoming a successful tattoo artist in both Shkoder, Albania and Prishtina, Sulejman Fani was told by his professors never to start. “I was studying in the Faculty of Arts in Shkoder, and professors told me that tattooing ‘isn’t for me,’” he said. “They said it’s dirty, and it’s not really art. But I did it anyway – I started it really to pay my way through school, I could do it on my own terms and have so much freedom. Now, I don’t need to do it for the money. We do well because people recognize that tattooing is an art form, now.”

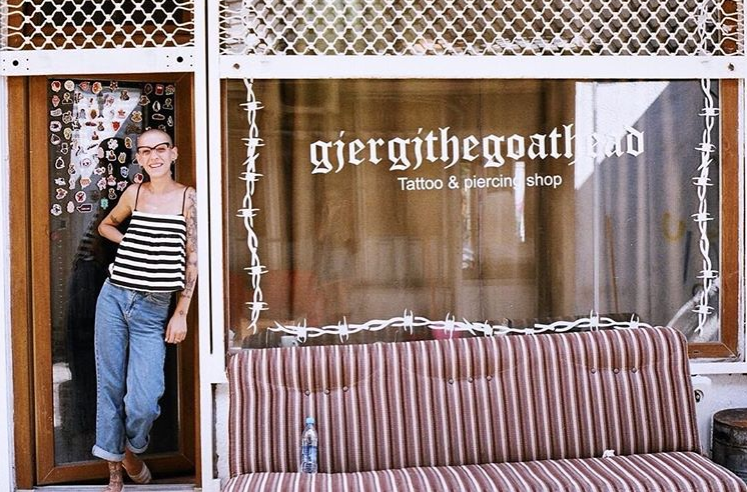

There is no tattoo artist in Kosovo that takes this freedom as seriously as Albana, who opened her studio named Gjergj the Goat Head earlier this year in Prishtina after using her apartment as a makeshift studio for years. For her, tattoos are more than just art, but a form of healing, both physically and psychologically.

“I’ve thought about spray painting ‘Therapy Sessions: 20 euros an hour’ on the window of the studio, because that would be the most honest depiction of what I do,” she said. “For me, tattooing is an experience that I get to share, from the moment you walk into my shop. I become a big sister or a little sister to people.”

Unlike the artists from Heavy Ink and Prishtina Ink, Albana embodies a certain spirituality and has an ethereal approach to the craft, viewing not just the tattoo as something permanent and life changing, but the entire process of tattooing itself.

“I’ve had many people walk into the studio and ask for tattoos like the infinity symbol,” she said, tracing the small figure-of-eight infinity sign against her wrist. “But not a single one of those people walked out with that tattoo. Once you sit down with someone and ask them why they believe something like that represents them, you discover that they were feeling scared of the idea of death, or something. I give people space to question their choices, and make sure they really feel like a part of their identity is going on their body.”

Albana has also been inspired by the traditional tattoo designs of the Balkans, and is doing her part to both immortalize this older style and reinvent it for present day.

“These old suns and tattoos were only ever tattooed on women, and as they vanished, this represented our historical shift from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society,” she told Prishtina Insight. “So I love reviving these designs, but I don’t leave them completely the same. I’ve started accompanying them with what Albanians call a ‘money plant.’ Many people keep them in their homes, it’s a small tree that is said to bring luck and prosperity.”

Through his anthropological research, Krutak has discovered others also working to revive this tradition. “Croatian tattoo artists Zele in Zagreb and Sasha Aleksander in Rovinj create contemporary forms of these ancient tattoos for their male and female clients. So there is a Balkan tattoo revival that is underway,” he said.

Tattooing means absolute freedom for Albana, who said that she has always struggled to live life within rigidly designed societal expectations of happiness and success. “I am able to be myself completely now. I choose when my doors are open, if someone wants a tattoo at 3am, I’ll be there. I tried going to university, I was the art director of a company, I proved myself, but I realized one day that I needed to live honestly.”

Albana was able to start out tattooing when a friend of hers snuck a machine past customs from Berlin, practicing on herself and her friends, and slowly turning it into her livelihood.

The freedom this has given her she believes has brought real happiness. “Life in Kosovo is incredibly tough for so many people, but if you can work hard enough to break out of the cycle that so many people are trapped in, you can change your life and the lives of others. And in my own way, that’s exactly what I’m doing.”

While in the ‘70s, Gashi was desperate to hide his tattoos from the people around him, Albana and the other contemporary tattoo artists working and living in Kosovo can now proudly display their tattoos, their designs and their businesses to the world. Though some prejudice remains towards people with tattoos, they said, all are convinced that tattoos have finally been accepted once again as the art form they were seen as in the Balkans hundreds of years ago.