Lacking protection from employees and the state – victims of sexual harassment in Kosovo remain reluctant to speak out.

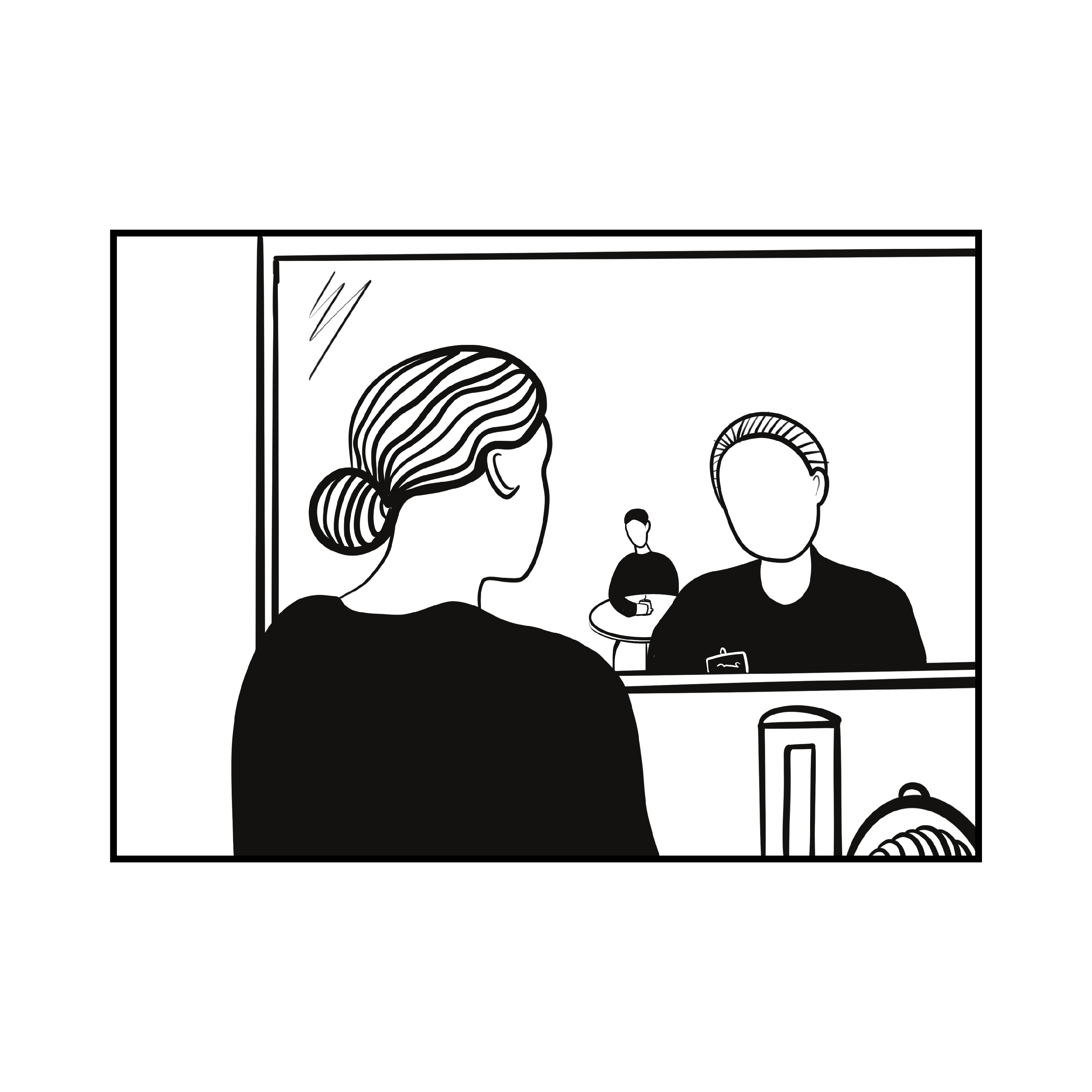

“Leona” has been working in a patisserie for the last four years in the Kosovo capital, Prishtina.

For her and other waitresses working in the city, the job often triggers anxiety due to the various forms of sexual harassment they encounter, ranging from whispers to stalking, stares and wolf whistles, from the cafe’s male clientele.

Carrying a tray full of drinks to serve, she says the mirror near the bar reflects the stares she receives from the men. “Through that mirror placed in the bar, we see the looks we get from clients,” the 24-year-old says.

“Verbal harassment is less common,” she says, “but when we serve on the balcony, and after we take the orders, we often hear unpleasant words.”

Complaints are almost fruitless. Leona and her colleagues were ignored when they spoke out about the men’s behaviour, she says. When they reported cases to their manager, the reaction was minimal.

“When we identified our harassers and told our manager, the only measure suggested was not to serve them,” Leona recalls.

Stigma and lack of trust deter reporting

Kosovo’s 2015 Law on Gender Equality is explicit in outlawing “any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature occurs, with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person,”.

In practice, reporting sexual harassment carries a stigma, and no adequate measures are in place to protect the wellbeing of those who report harassment, say human rights activists.

There are no exact data on sexual harassment in the workplace in Kosovo.

Police say that between January and March, only four cases were reported to them. During the whole of 2020, 48 cases of sexual harassment were recorded, but without details about whether it took place in the workplace or elsewhere.

Liridona Sijarina, who researches sexual harassment at the workplace for Kosovar Gender Studies, an NGO, says the low level of recorded harassment does not reflect reality.

“From field work, we can see that women are harassed in the workplace a lot, but they do not report it to the police or to the workplace because they lack trust … in official structures,” she told Prishtina Insight.

“In many workplaces, women are not even aware of the rules that can protect them from being harassed,” she adds.

Sijarina believes a patriarchal mindset is reflected in the behaviour of law enforcement institutions, resulting in women experiencing prejudice instead of being protected.

“Women do not want to go somewhere where they will be blamed,” she says.

Many fear losing their jobs

“Fjolla”, a journalist in Prishtina, is among those who never reported sexual harassment at the workplace, either to her employees or to the police.

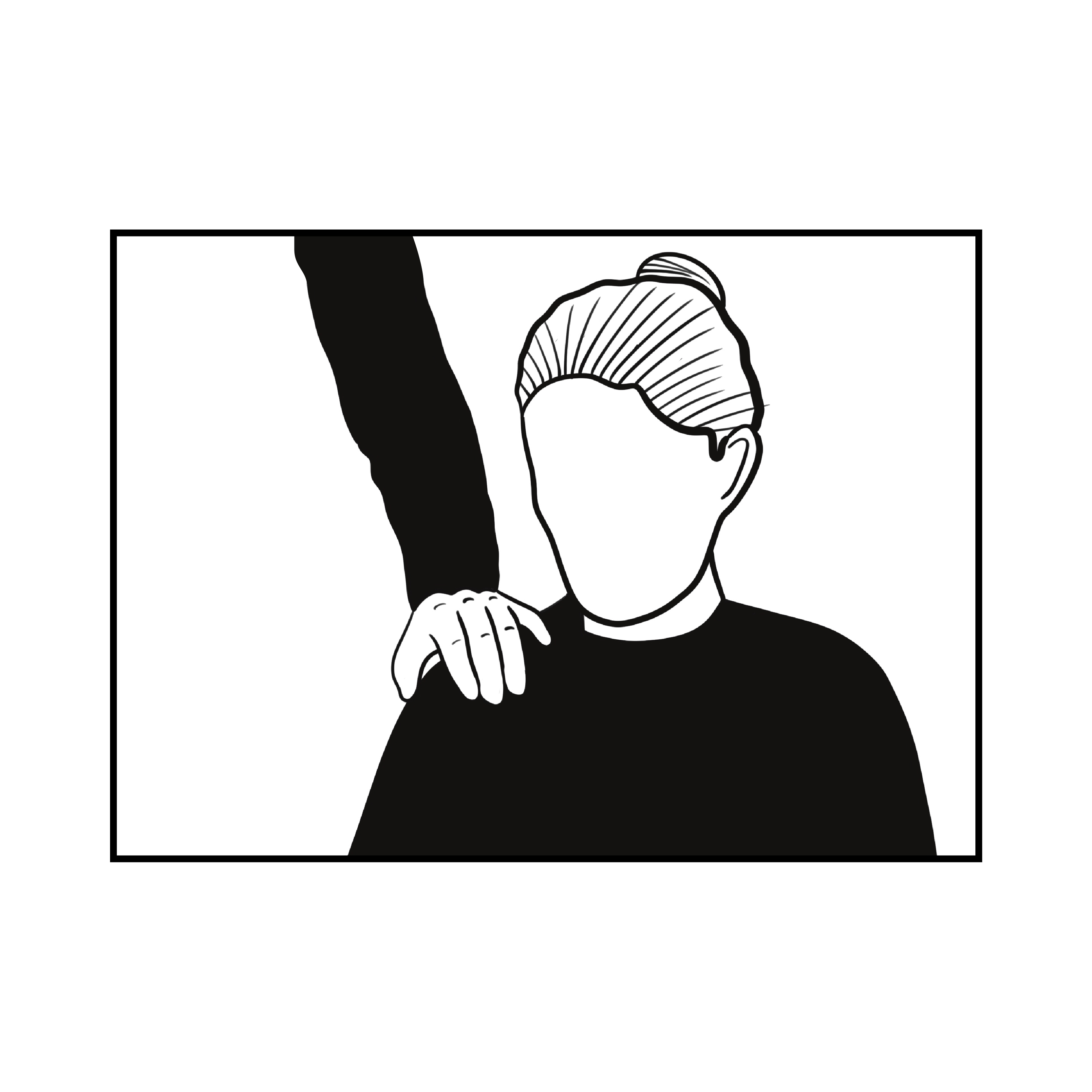

She vividly remembers the anguish she experienced when a colleague started harassing her while they were on fieldwork, which continued in the office and almost escalated to the level of assault.

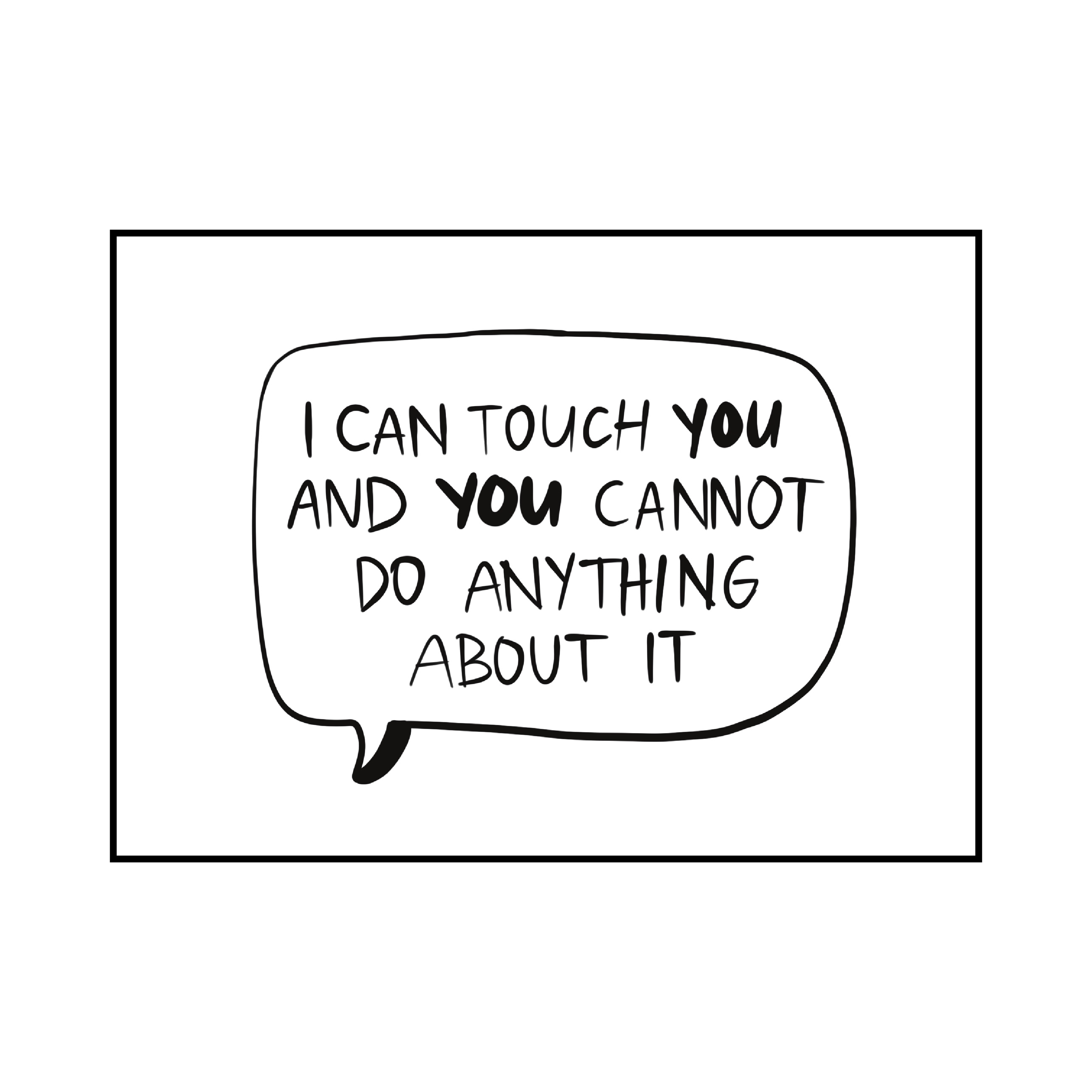

“I was told that, ‘I can touch you and you can’t do anything about it,’” she recalls. “In one instance, when I was telling him that he cannot do that, he almost threatened me,” she says.

She says she felt fearful to report the matter to her supervisor in case she lost her job. “I was afraid to tell them and be fired,” she says.

Eventually, her harasser left his job and Fjolla felt a bit safer.

Sijarina says Kosovo women are also affected by the low level of inclusion of women in the workforce and the overall lack of opportunities, which makes women more vulnerable to sexual aggression.

During 2020, according to the Agency of Kosovo Statistics, the rate of women involved in the formal market was 14.1 per cent, compared to 44 per cent of men.

Sijarina further adds that, along with unemployment, other forms of stigma are to blame for the low level of reporting of harassment at the workplace.

“Women feel that their integrity will be in jeopardy if they report sexual harassment in a society where women are blamed for ‘provoking’ men,” she says.

For Fjolla, sexual harassment is an ordinary “ugly practice” she experiences often in her journalistic work.

“I had one case with an interviewee who, when we were done with the interview, gave me a very different hand-shake,” she recalls.

“Immediately after I returned to the office, I also received a message: ‘You have the physique and look of a princess,’” along with an invitation to go for a ‘coffee’.”

However, Fjola, says that today she is more resistant to sexual harassment and regrets that she did not react more firmly in the past.

“If I could go back in time, I would report any sort of harassment, either to the employee or to the police,” she concludes.

*Names have changed to protect the identity of interviewees.