The short-lived campaign for the June 2017 snap elections reveals stark inequality between men and women in Kosovo politics.

The original version of this story was published by Preportr.

During the campaign for the last national elections in Kosovo, all nominees for prime minister were men, 70 per cent of the candidates in the electoral lists were men, cities were filled with posters of men, television debates were full of men talking to men, while in rallies, both the speakers and the audience were predominantly men.

This is not strange for a society with patriarchal values, where women encounter practical obstacles to joining the electoral campaign, including prejudices on their public activity, lack of financial resources, a low level of education, lack of space in decision-making within political parties, discriminatory representation in the media, and the large responsibility for their families, which limits their participation in public activities.

As a result, most women, especially those who run for the parliament and even moreso those who run for the first time, could not occupy an equal space with men even during the 2017 general elections.

Financing

The impact of money on the election campaign has hardly ever been discussed. But, as the costs of election campaigns increased, so did the competition between MP candidates. The only two parties who responded to Preportr’s queries, Vetevendosje and the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo, AAK, said that all MP candidates fundraised and paid for their own campaigns, with the exception of candidates for prime minister.

For MP candidates this translates to the simple fact that those with greater income are able to buy more space for themselves and are at a greater advantage to get votes.

More importantly, money is making the competition between men and women nominees an unequal race. In general, women have less financial resources compared to men, especially in Kosovo, where the number of unemployed women is the highest in the region. According to the Kosovo Agency for Statistics, 80 per cent of women are unemployed.

Shqipe Gjocaj, a women’s rights activist, explained that the economic situation of women in the country is connected to the possibility of affording an expensive campaign.

“Running a campaign that provides you with visibility requires money, and the economic situation of women is certainly one of the key limitations for women nominees,” she said.

The organizations Cohu and Democracy Plus monitored the spending of political parties during the 2017 electoral campaign. Spending on TV advertisements, online outlets, newspapers and billboards has been analyzed by Preportr from a gender perspective. The results reveal that in all sectors of advertising, male candidates have invested more than women.

The streets in cities are overloaded with billboards and posters, but rarely could a woman be seen. When monitoring 269 billboards in some Prishtina neighborhoods during the last three days of the campaign, Preportr found only eight billboards promoting women nominees.

A large number of MP candidates invested in online media advertisements. Preportr has found that out of 746 advertisements in online outlets, 82.31 per cent promoted men, while only 17.69 per cent promoted women.

Similar results came from monitoring advertisements in five daily newspapers. From 218 advertisements, only 19.27 per cent promoted women nominees, while 80.73 per cent promoted men.

The greatest investment during this campaign was in TV commercials, however. In addition to the production costs, nominees paid a hefty sum for broadcast. Since these commercials are very costly, women nominees had an even lower presence on TV.

From 40,559 seconds of commercials that Preportr monitored, 88.36 per cent promoted men, while only 11.64 per cent promoted women. The monitoring did not include advertisements for the party itself or the PM candidates, because if they had been included, the representation of women would have been even lower. Most party-specific ads highlighted only male candidates or leaders.

The low number of women in public debates

Since the June elections were extraordinary elections and political parties compiled their lists of candidates in the last minute, campaigning for women was even more difficult. With the exception of former female MPs or women who held an important position before, other female candidates had no recognizable persona. A great role in this was played by the media, and especially the television debate in which candidates were invited to present their political programs.

Since the official campaign lasted only ten days, political parties ensured that nominees that were already familiar to citizens would appear in public debates. Unfortunately, most of these were men.

Besa Shahini, a political analyst, sees this as a result of the quota system which guarantees 30 per cent of the Assembly seats to women MPs. As a result, parties do not think women do need the exposure as much as men do.

“Women have a lower participation in policy making, due to the continuous oppression that makes them less outspoken and less represented. So when parties decide to send someone to rallies or debates, they go with men because they are the most ‘competent’ since they participated in decision-making processes,” she said.

“Women have a lower participation in policy making, due to the continuous oppression that makes them less outspoken and less represented. So when parties decide to send someone to rallies or debates, they go with men because they are the most ‘competent’ since they participated in decision-making processes,” she said.

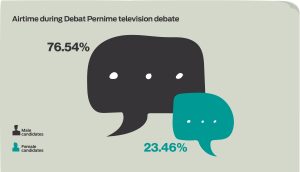

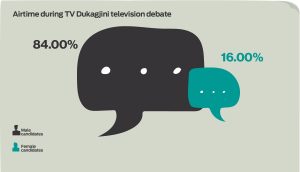

According to a Preportr analysis of various TV debates, the participation and presence of women was much lower than that of men.

Regardless of the fact that the producers of “Debat Pernime” asked parties to send at least one woman representative, among the necessary three participants, most parties did not stick to this rule. Of 81 MP candidates that appeared on the show, 62 were men and 19 were women.

Meanwhile, in the daily electoral debates on TV Dukagjini, from the total of 25 nominees who appeared only five were women.

In this low level of representation of women nominees, the latter have not been able to use TV debates to present their political platform and as a result were overshadowed by men in their parties.

According to a National Democratic Institute, NDI, report from 2015, 62 per cent of women who participated in the survey believe that there is no strategy in the media that promotes the image of women in politics.

Linda Gusia, professor in the Philosophical Faculty at the University of Prishtina, believes that the domination of men in election debates is telling of a lack of basic equality.

“When it comes to representation, which is almost a formal one, there is not even a small attempt in political parties for improvement. We should insist in greater representation of women in the public sphere,” she said.

According to Gjocaj, the lack of women in TV debates is a clear indicator of the mentality of male politicians.

“They preoccupy themselves with filling the gender quota to fulfill what the law requires and they do not care further… Gender equality of which they attribute to their parties is totally superficial,” she said.