A single businessman in Kosovo stands behind six companies reaping millions of euros from the sale of solar energy in violation of anti-monopoly rules, a BIRN investigation has found.

Sunlight glinted off row upon row of solar panels stretching into the hills around the village of Madanaj in western Kosovo.

It was October 2018 and the country, a little over a decade old, was unveiling its first solar park a few kilometres from the site where Serb security forces executed 376 ethnic Albanian civilians in April 1999 in the worst mass killing of the Kosovo war.

If the massacre at Meja marked the darkest moment in Kosovo’s quest for independence, the new solar park was surely a shining example of how far it had come since independence from Serbia in 2008, of its technological advancement and ambition to be free of the coal-fired power plants that have clogged the lungs of generations of Kosovars.

That might have been the case, if only the cards had not been stacked to benefit one very rich man, the ultimate owner of the solar park and who now stands to reap some 27 million euros of taxpayers’ money over the next 12 years in violation of rules drawn up to prevent the emergence of monopolies in the energy sector.

While the rules in Kosovo stipulate that no single investor can produce more than three megawatts of solar energy, BIRN can reveal that one man – Blerim Devolli – stands behind six companies awarded rights to produce a combined 16.7 MW, more than half of Kosovo’s total solar power production.

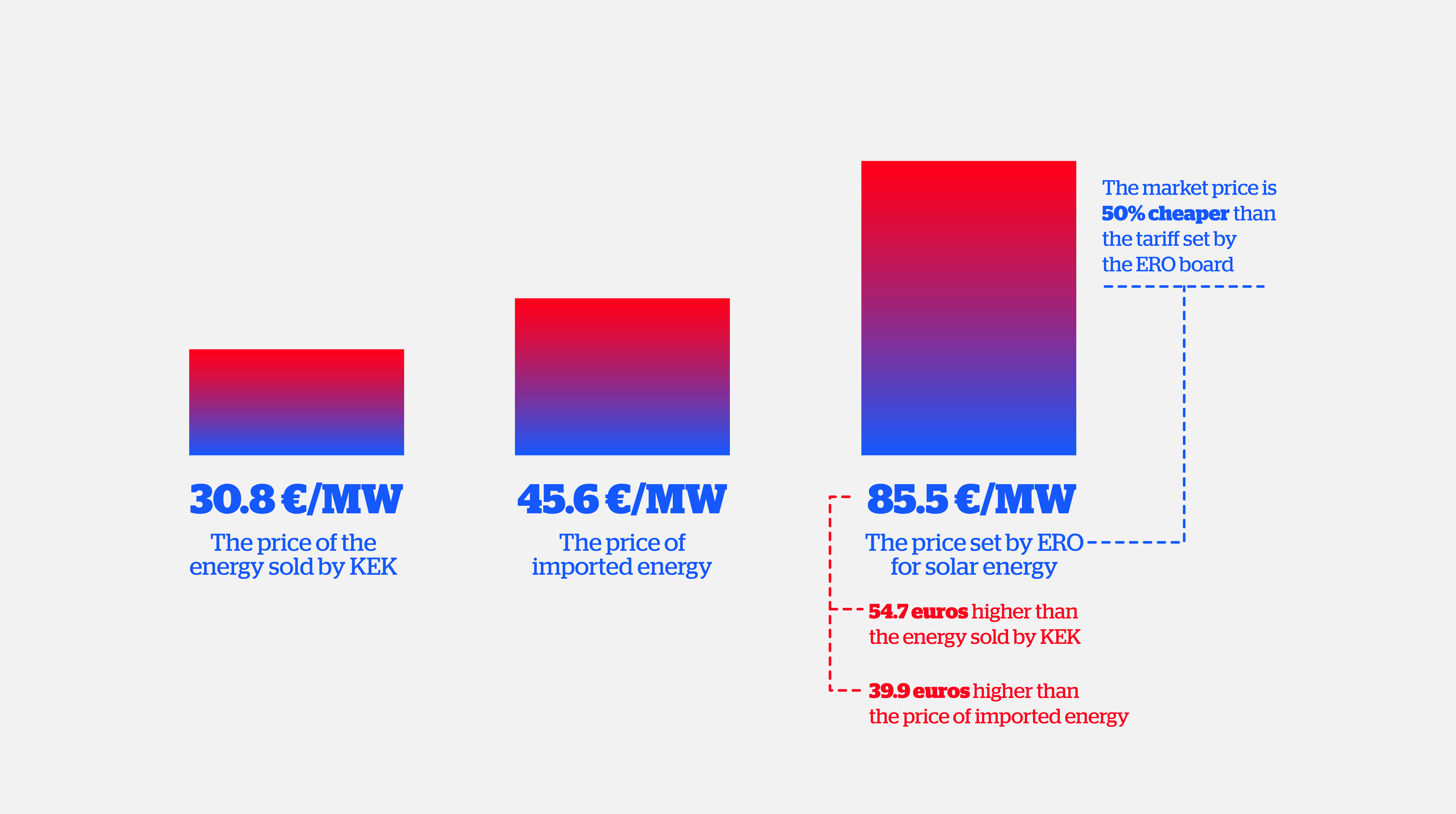

And each of these companies will receive a guaranteed price from the state – a so-called ‘feed-in tariff’ –between two and three times higher than the going market rate under a decision by the industry regulator, the Energy Regulatory Office, or ERO.

The ERO told BIRN it does not have the mandate to check the ownership of companies it does business with. On May 12, Devolli’s holding company, Devolli Group, rejected the findings of this investigation, which was first aired on April 30 on BIRN’s Jeta ne Kosove current affairs programme. Devolli did not respond to several interview requests for this story.

Nevertheless, prosecutors are probing whether to launch a criminal investigation on the basis of BIRN’s findings. Critics say that what should have been a story of clean energy and new beginnings has become a familiar tale of dirty dealings.

Corruption warnings ignored

Devolli’s business interests do not stop at solar energy.

Via the Devolli Group holding company, the 48-year-old makes money from the sale of beer, fruit juice, dairy products, water and a virtual mobile operator. His brother, Shkelqim, presides over Devolli Corporations, which has interests in shock absorbers, television, customs and coffee. Other businesses are registered under Devolli Holding SH.P.K and Devolli Logistic System ShpK.

Devolli’s owns a Range Rover with diplomatic licence plates thanks to his status as a consul in Albania, yacht anchored in the Montenegrin tourist town of Budva.

He is also, however, the ultimate owner of six companies registered in European Union-member Malta, according to the results of a four-month investigation.

Devolli’s dealings in solar power date back to November 4, 2014, when the brewery he bought the same year – Birra Peja – applied for a licence to produce solar energy. Six weeks later, another company, Frigo Food Kosova, also sought a licence.

The ERO granted both licences on May 19, 2016, handing them a whopping feed-in tariff of 136.4 euros per MW, which, according to the Vienna-based Energy Community Secretariat – an international body working to extend the EU’s internal energy market rules to neighbouring countries – is three times the current market price.

Feed-in, or incentive, tariffs are fixed prices at which the ERO guarantees to investors that it will buy all the energy they produce over a 12-year period, a price passed on to consumers via their electricity bills.

Exposing Devolli’s hidden companies

Investors are selected on a ‘first come, first serve’ basis rather than via open competition in which rival firms would seek to offer the most competitive price.

It is a method that was criticised in separate letters to the ERO last year from the Energy Community Secretariat, the US overseas development agency USAID, the German embassy in Pristina/Prishtine and the European Commission, the executive arm of the European Union.

The Germany embassy, in its May 2019 letter, said such a practice “carries a risk of corruption and unnecessary pressure from unreliable developers on the government and the ERO.”

The German letter looks prescient in the light of BIRN’s findings.

Regulator lacks “mandate” to examine investor links

While Devolli was always known to have bought Birra Peja, BIRN has discovered that he also stands behind Frigo Food Kosova, meaning that Devolli, as a single investor, had been handed rights to produce six MW of solar energy, double the limit stipulated under ERO rules.

Devolli’s ownership of Frigo Food Kosova is concealed behind a shell company registered in Malta under the name Frigo Food Solar. Likewise, beer drinkers in Kosovo may be surprised to learn that Birra Peja is owned by the Maltese-registered firms Abrazen and Globusus, though it was always common knowledge Devolli had his hand on the taps.

Asked why it had assigned two licences to two companies with the same owner, when ERO rules prohibit any one investor from selling more than three MW of energy, the ERO told BIRN that it “does not have the mandate to identify connections between these companies.”

“Based on the legal framework, after their application, the ERO treats companies as legal entities established under the Law on Business Organisations, and after completing all relevant steps, issues the preliminary authorisations,” the regulator said in its written response on March 11.

“The ERO has always treated them as projects, and for each project, the legal entity had to be provided with both consent and permits issued by the relevant institutions,” it added.

That is in spite of the fact that the entire ERO board was filmed by a local TV channel, TV SyriVision, as guests of Devolli at the inauguration of the first solar park in October 2018, which is owned by the two companies in question – Birra Peja and Frigo Food Kosova. Speeches and promotional material lauded the launch of six MW of production, double the permitted amount.

Devolli, however, did not stop there.

On November 27, 2019, the ERO granted another eight companies feed-in tariffs to produce 20 MW of solar energy. Four of those companies, according to BIRN’s findings, are ultimately owned by Devolli – Building Construction Kosovo L.L.C., Alsi & Co Kosova, Energy Development Group and the Devolli Group. All are owned by Maltese shell companies with the exception of Devolli Group, which was initially registered in Kosovo but later renamed Abrazen L.L.C., owned by Malta-registered Abrazen LTD.

Each was granted a feed-in tariff of 85.5 euros.

Building Construction Kosovo L.L.C., which was awarded a licence to produce 1.73 MW of solar energy, is a Kosovo-registered company owned by Maltese-based Solar Power Holding;

Alsi & Co Kosova is owned by Maltese-registered parent company Alsi & Co Ltd; Energy Development Group, registered in Malta, is owned by EDG Ltd.

Having tracked the companies to Malta, BIRN paid the standard fee to access each registration in the Malta Business Registry and finally reach the name of the true owner.

According to the registry, all three parent companies are owned by Devolli, who is registered under the Montenegrin citizenship that he holds alongside his Kosovar. All his businesses in Malta are registered at the same address and represented by Wilhelmus Adrianus Woestenburg, who, according to revelations from the Panama Papers, is the legal representative of 150 business entities.

In a statement on May 12, the Devolli Group said Devolli had made no secret of his holdings in Malta and that there was nothing wrong with registering them on the island, which, it said, has “transparent standards compatible with the EU.”

It also denied there was anything wrong in one person owning a number of companies licenced by the ERO, saying other investors had employed the same practice and that it is not ruled out by ERO regulations. Comparing the feed-in tariffs offered by the ERO and energy tariffs elsewhere in the region is inappropriate, it said.

The Kosovo Renewable Energy Association, an industry body, also rejected any comparison between prices in different states and said BIRN’s “attack” on renewable energy projects was tantamount to support for energy imports from Serbia.

However, Kosovo’s State Aid Commission, CSA, which is tasked with ensuring a competitive environment in all areas in which the state offers up resources for exploitation by private investors, saw things differently.

On May 8, a week after this investigation was first aired, the CSA said in a statement that it had started an investigation and had given the ERO 15 days to respond to its queries:

“The limit of those who ought to benefit from this feed-in tariff is three megawatts,” the CSA said. “We are concerned that the ERO has, with their decision, avoided fulfilling this legal obligation.”

Also on May 8, the speaker of the Kosovo parliament, Vjosa Osmani, sent a formal request to MPs on the assembly’s economics commission to look into the matter, while State Prosecutor Sevdije Morina said special prosecutors were gathering information to determine whether there were grounds for a criminal investigation.

Change of heart

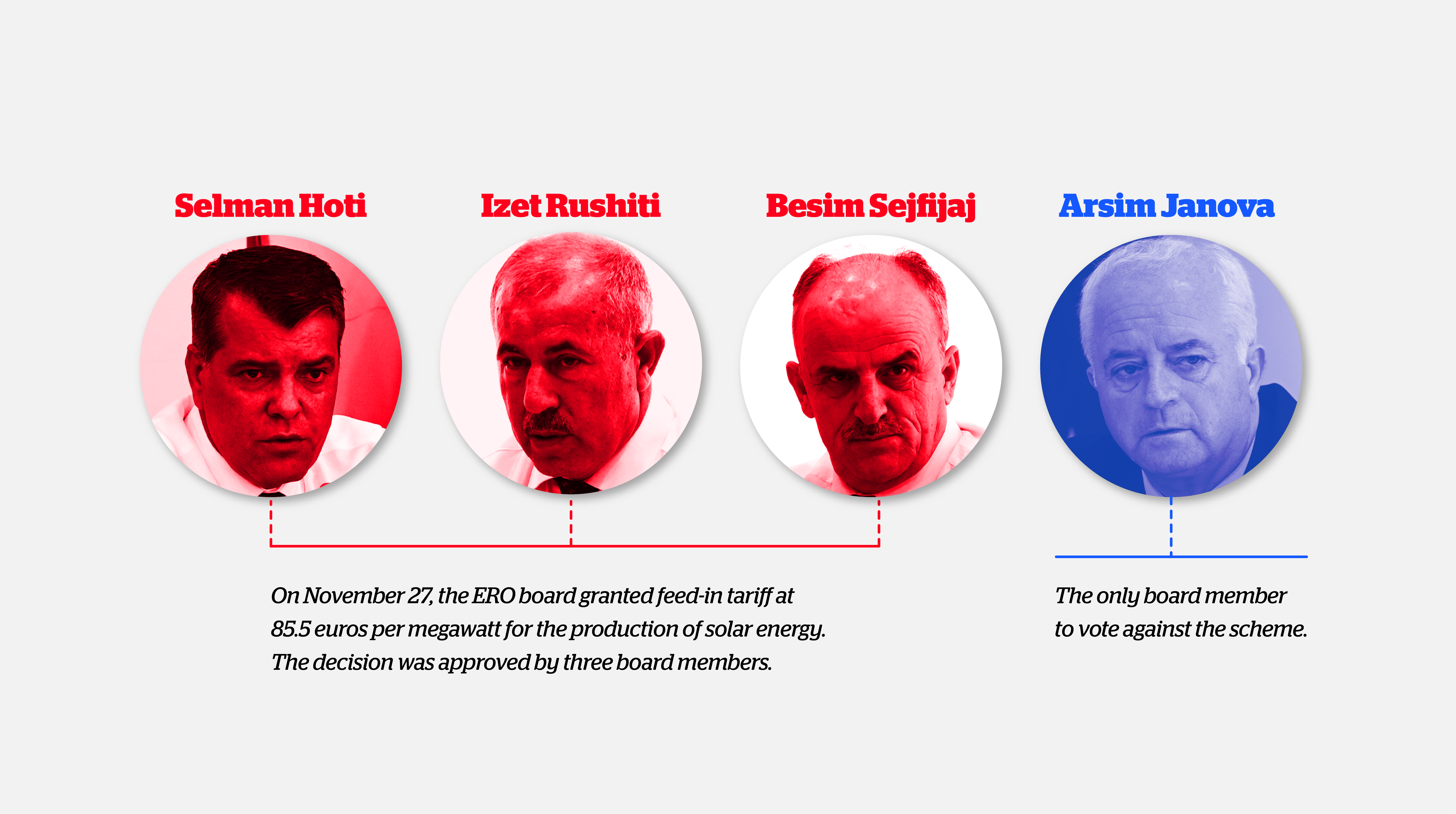

Intriguingly, the ERO board, at a meeting on October 14, 2019, had voted against the licensing of another 20 MW of solar energy via feed-in tariffs. BIRN filmed the meeting, which was visibly tense.

ERO legal officials Afrim Ajvazi and Ymredin Misini cautioned those present that failure to approve feed-in tariffs for the extra energy could result in the regulator being brought to court.

ERO chairman Arsim Janova asked, “Which operator could sue us? Do you actually know who could take us to court?” Without naming names, Misini replied, “I mean, in principle, they can sue us,” to which Janova responded, “Are we actually looking at fulfilling the requests of one particular operator here?”

Janova voted against the feed-in tariffs for the extra energy, as did board member Besim Sejfijaj.

The two other members of the board, Izet Rushiti and Selman Hoti, were in favour, but ultimately lost.

Sejfijaj made the argument that an open competition could secure a more favourable price for the energy, echoing the advice of a number of international bodies.

“Why should the consumer, as well as ourselves, be charged for the feed-in tariffs when tomorrow, someone may come with [an offer of] 50 or 60 euros [per MW],” he said.

Fast forward 48 days to the November 27 meeting and Sejfijaj switched sides, voting in favour and clearing the way for the ERO board to set the feed-in tariff at 85.5 euros per MW. Janova was alone in opposing the scheme. Eight companies were allocated a total of 20 MW – 10.7 of which went to four companies that, it turns out, are controlled by one man – Blerim Devolli.

To date, no evidence has been produced that would suggest the ERO faced any risk of being challenged in court.

But it would not be the first time that public officials have faced the threat of legal action from wealthy private interests.

In 2015, Devolli’s telecommunications provider, Z Mobile, took state-owned Kosovo Telecom to the Court of Arbitration. He won, and Telecom was ordered to pay compensation of more 25 million euros.

‘What’s a man to do?”

ERO board member Selman Hoti, who lobbied hard for the feed-in tariffs, is also the shareholder of an energy company called Electra, which was contracted to install cables at the Devolli solar park that was eventually launched in October 2018. Electra received the contract before Hoti’s appointment to the ERO board in March 2018.

Hoti told BIRN he had asked Kosovo’s Anti-Corruption Agency, AKA, whether this represented a conflict of interest but said that he did not receive a reply.

“Back then I was not a member of the [ERO] board, nor did I have any connection with the ERO,” he said. “We [Electra] executed part of the construction; we laid down a cable to the main station in Gjakova in order to connect it with the solar panels.”

“What’s a man to do – starve just because I’m a board member?”

According to Hoti’s public declaration of assets, he receives a salary of 1,950 euros per month from the ERO [almost four times the Kosovo average] and has 147,000 euros of family savings in the bank.

According to its website, Electra has also carried out regular work for electricity distributor KEDS [Kosovo Energy Distribution and Supply Company], which the ERO is tasked with regulating. As an ERO board member, Hoti is involved in decisions that affect the profit of KEDS on a regular basis.

The Anti-Corruption Agency, asked whether Hoti’s affiliation with Electra represented a conflict of interest, replied that it had opened an investigation based on BIRN’s questions.

Izet Rushiti, who voted with Hoti in favour of the feed-in tariffs, previously ran for the local assembly in 2017 as a candidate of the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo, AAK, led by former Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj.

Of the four other companies selected alongside Devolli’s four, two – Vita Energy and VBS – are owned by men with close ties to Haradinaj – Rasim Merlaku and Valton Bilalli. Haradinaj and his brother, Daut, both live in the plush Marigona Residence development of luxury housing some 20 minutes by car from Prishtina. The neighbourhood was built by Merlaku, Bilalli and a third man. According to social media posts, Merlaku regularly goes hiking with Haradinaj.

Both Hoti and Rushiti were appointed to the ERO board by Kosovo’s parliament in March 2018, when the AAK was part of Kosovo’s coalition government and Haradinaj was prime minister.

British experts, who were tasked with monitoring senior public sector recruitment under a 2016 deal between the UK and Kosovo governments designed to improve cadres and weed out unqualified party-political appointees, had argued that neither man met the criteria to sit on the ERO board having fallen short of the required number of points during testing and interviewing.

Lawmakers, however, ignored the British advice.

‘What’s wrong with Blerim Devolli?’

Feed-in tariffs are designed to guarantee companies a return on their investment in the production of renewable energy, while also guaranteeing the sale of all they produce at a fixed price. Under ERO rules, the difference between the average energy price and the feed-in tariff is passed on to consumers via their electricity bills.

The price set in November 2019 by the ERO for solar energy – 85.5 euros per MW – is 54.7 euros more than the energy that is produced by the Kosovo Energy Corporation, KEK, by burning lignite. It is also almost 40 euros more than the price of energy imported by Kosovo.

Arben Kllokoqi, an energy expert at the Energy Community Secretariat, told BIRN that countries that have used open competition to support solar energy production have benefited from much lower prices. In neighbouring North Macedonia, for example, prices are roughly half the 85.5 euros per MW set by the ERO.

Moreover, on May 27, the Albanian Government launched an open competition for investors for the production of 140 MW of solar energy. For 70 MW, the government secured an incredible price of 24.89 euros per MW, 60 euros cheaper than the price the ERO allocated to the 20 MW granted to companies in November. The remaining 70 MW is expected to be purchased at market price.

In an op-ed published after BIRN’s investigation first aired, Adhurim Haxhimusa, a Kosovar energy expert who teaches at the University of Applied Sciences of the Grisons in Chur, Switzerland, said he had conducted a comparison of the subsidies Germany and Kosovo pay for renewable energies.

“Germany pays only 0.75 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per year in subsidising renewable energies, while Kosovo pays over 2.02 percent of its GDP for this,” he wrote. “So the average Kosovo citizen pays 2.7 times more than the average German citizen.”

The ERO, however, told BIRN: “Currently, the feed-in tariffs are the only support scheme that would allow Kosovo to achieve its targets for reliance on renewable energy sources.”

As for the cost to consumers of the feed-in tariffs for 20 MW decided in November 2019, the regulator said it would come out at 27.6 million euros over 12 years, or 2.29 million euros per year.

Devolli stands to pocket 14.4 million euros of that sum, unless the courts intervene to annul the ERO decision. According to BIRN’s calculations, he will also receive 13.2 million euros via the feed-in tariffs already granted to Birra Peja and Frigo Food Kosova in 2016. That comes to a total of 27.6 million euros from Kosovo’s electricity consumers.

In December, two members of the Vetevendosje party that currently heads Kosovo’s caretaker government – former Kosovo ombudsman Sami Kurteshi and commercial lawyer Geotar Mjeku – filed a complaint with the Kosovo courts challenging the ERO decision of November 2019 based on the suspicion the same investor stood behind more than one of the selected companies. This story confirms that suspicion.

“This is being done without any competition and contrary to all market competition rules,” Kurteshi told BIRN.

On April 6, the Basic Court accepted a request from Vetevendosje for an injunction to stop the ERO from implementing its decision until a final ruling from the courts.

Kurteshi alleged collusion, telling BIRN: “There is a strong connection between the ERO and the oligarchs and they [the oligarchs] also want to influence the courts. This should not be allowed.”

On April 27, three days before airing its investigation, BIRN doorstepped ERO board member and Electra shareholder Hoti at his office.

Pressed about the risk of creating a monopoly in the solar energy sector by handing Devolli such a degree of control, Hoti replied: “Tell me, what’s wrong with Blerim Devolli? If not Devolli, it’ll be some Chinese [investor]. Is that what you want?”

Dorentina Kastrati, Astrit Perani and Faik Ispahiu have contributed to the investigation.