Meet Kosovo’s fledgling generation of interns.

I met Tanita Zhubi, a twenty-something-year-old employed at a local non governmental organization and an old friend, on a spring day. As we reminisce about old times, we end up talking about the days when we worked at an art institution in Prishtina. She interned there long before I joined, and in a way, ushered me into the daily tasks. Although many years passed since then, things become clearer in retrospect.

“I had no idea what I was supposed to do,” she told me. “Whatever there was to do, they would throw it on me: from putting up posters, buying plastic cups, all the way to organizing the logistics of art events, as well as working as an administrative assistant.”

“Did you at least learn something during that time?” I inquired.

“Professionally? Not really. I thought that at least by being in contact with different people, I would get to learn something and would create a network of people. But that didn’t turn out to be so either,” Tanita responded, before adding mirthfully, “Although, I did manage to develop ‘a skill’ to agree with people, even when they themselves have no idea what they’re talking about.”

Tanita’s internship experience is a common one in Kosovo, a market inundated with young people, as 60 per cent of the population are under 35, and about the same percentage are unemployed.

Globally, employers are spending less and less time, money and effort on staff training. As a result, the entire burden of attaining qualification, including the costs, falls upon the employees themselves.

In Kosovo, entry level positions are few and far in between and vary largely from sector to sector. Meanwhile, on-the-job trainings are a rarity, at least among advertised jobs. Most vacancy announcements require that applicants have completed higher education and have worked from two to five years in the field.

Thus, for many inexperienced and unemployed youngsters, internships are the only way to gain the necessary skills and work experience to be able to have the slightest chance of employment.

I did manage to develop ‘a skill’ to agree with people, even when they themselves have no idea what they’re talking about.

However, minimally regulated within the current legal framework, interns are often exploited by being overworked, given trivial tasks with no real skill development opportunities, having no mentors, often working without a contract at all, all the while being denied compensation for their efforts.

“You take an internship to improve your ‘experience package,’ and not to volunteer or be exploited,” said Linda Gjokaj, the co-founder of the Pay My Internship initiative, a recently established NGO. After talking to numerous young people and drawing from their own experiences, Gjokaj and a group of friends decided to tackle unfair conditions of unpaid internships, which she says are “an abuse of human rights.”

Gjokaj’s organization is one of a kind in terms of its approach to internships as a labor rights issue. They are focused on raising awareness about unpaid and non-qualitative internships as well as advocating for a specific law that would regulate these issues.

“Interns have expenses, especially if they have to intern in another city. At the very least these expenses should be covered – not to mention that they work like regular employees,” said Gjokaj, adding that the current law is too vague.

Internships are covered by the Law on Labor, according to which employers have the right to decide on pay, duration of the internship (with a maximum of six months for high school graduates and one year for university graduates), as well as other rights that may come out of an employment agreement. In turn, the intern must follow all of the rules and regulations of the workplace. Since the law does not specify intern rights and does not mention working hours and overtime, it creates legal loophole for employers to demand interns to work overtime and during weekends, without compensation.

Moreover, in many cases contracts are not even provided to interns – as the law states only that “employers may sign a contract” – leaving many interns without legal protections.

Having the convenience of a labor market filled to the brim with young job seekers without social safety nets, employers are in a better position to dictate the terms of the contract and the duration and quality of the internship.

Interns have expenses, especially if they have to intern in another city. At the very least these expenses should be covered.

This happens even in state institutions, as it did to Nora*, a young graduate student who interned without a contract for the Kosovo embassy in Berlin.

Nora, who finished her studies and has not found a stable job yet, was at the time looking for a thesis-related internship in Germany, since her research was focused on Kosovar diaspora businesses. She wrote to Kosovo’s embassy in Germany with hopes that interning there would give her better access to information and to the diaspora business community.

“When they saw my email requesting an internship, they immediately said yes,” she explained.

“It was only later that I realized that they were in dire need of staff but were unwilling to hire anyone new and that’s why they accepted me as an intern,” Nora said, adding that it was only through her persistence that she managed to give purpose to her internship.

“They put me in this room with papers and files all over the floor and desks, which happened to be various official applications and documents. So I had to arrange and systematize them, and afterwards, digitalize all of them. It took me weeks to arrange it.

“In the end I got a letter of recommendation and another title in my CV, though in my experience, employers may not even consider an internship as a valid experience,” she concluded.

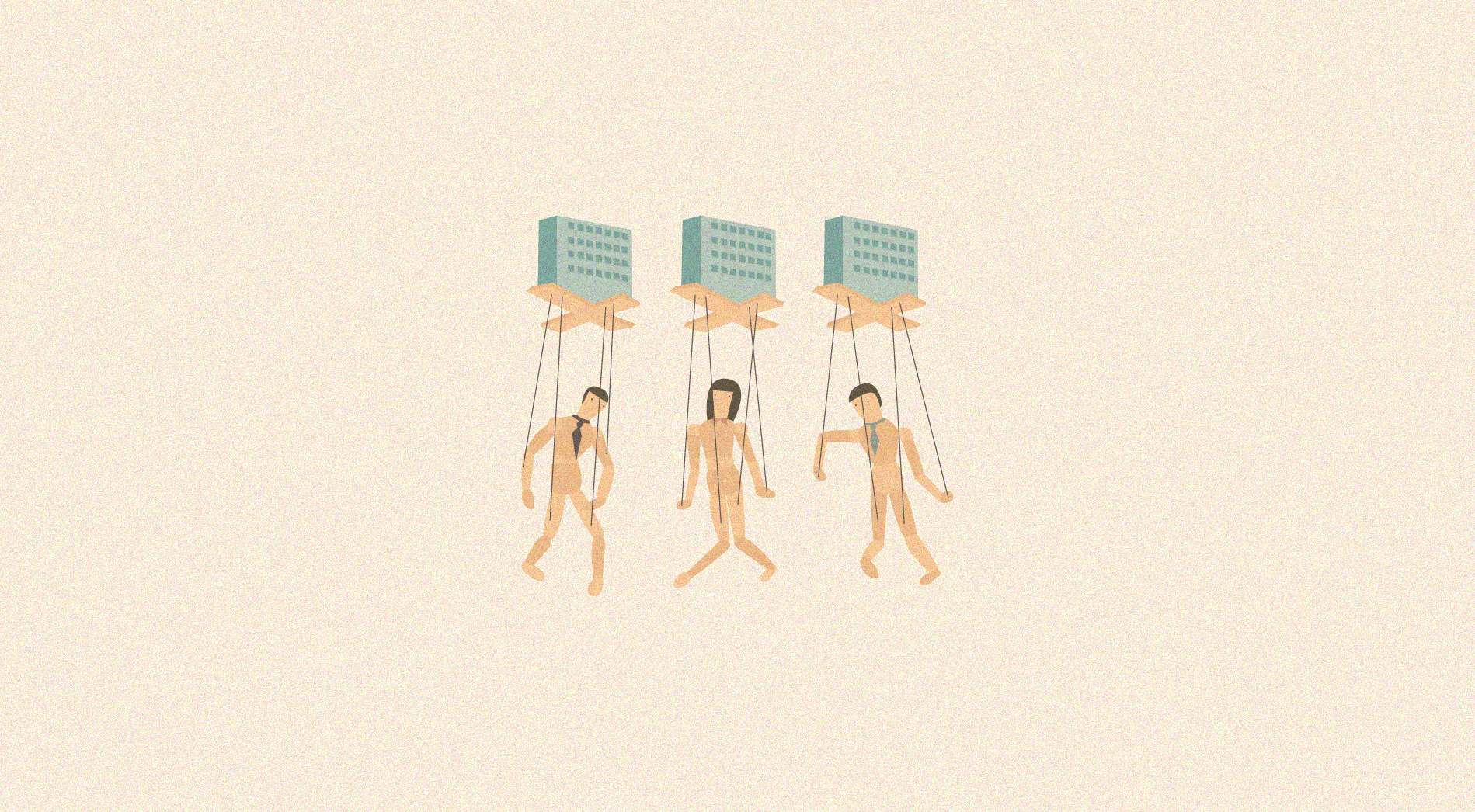

Illustration Jeta Dobranja/ Trembelat.

Both the government and international institutions in Kosovo consider internships as a way to tackle youth unemployment and the low skill-level of the labor force, both in the public and private sectors. In the past, the Ministry of Finance signed a memorandum with the University of Prishtina to employ up to 600 interns in 2016 alone, while the Ministry of Diaspora introduced an internship program for 3,000 students and recent graduates. Meanwhile, international organizations like the German development agency GIZ, USAID and UNDP also support various programs on youth employment, including internship possibilities.

Often internships reflect the direct needs of the specific employer and may be irrelevant to other employers even within the same sector. For example, programs such as ProCredit’s “Young Bankers” or the Raiffeisen Bank internship program are more focused on teaching their interns about their own products rather than the inner workings of the banking system.

Another prime example of the private sector’s approach is the academic and internship program of KEDS, Kosovo’s privatized electro-distribution corporation. Together with the University of Prishtina and the Turkish Bogazici University, they offer a mixed program of academic courses and internships for 50 students per year through the KEDS Academy. The program is in its fourth year and has prepared around 200 trainees.

“It’s a year-long program at the end of which the students have an internationally recognized degree and develop skills mostly related to KEDS and electro-distribution, “ said Viktor Buzhala, KEDS’s spokesperson, referring to the KEDS Academy diploma that the students get.

But who will pay for my rent and bread if I’m doing it for free?

The program lauds its own merits, claiming that interns are paid and the majority of them find a place within KEDS and KesCO as part of their pledge for Corporate Social Responsibility.

On the other hand, the representative of the KEDS workers union Hysni Gashi says that the KEDS Academy plays a more sinister role. The union claims that they are using the KEDS Academy to create qualified labor only for themselves, as well as to hire employees with short term contracts. Meanwhile, the union claims, KEDS is unlawfully and collectively laying off older workers with permanent contracts.

“They fired 320 workers and hired 160 new workers that went through the KEDS Academy training, paying them almost twice less than they paid those who were laid off,” Gashi said, adding that the KEDS Academy is a PR tactic used to improve KEDS’ image.

Meanwhile, some companies, argued Linda Gjokaj, rely on free intern labor for their survival.

“Some media portals have only two full-time employees and three interns that rotate constantly,” Gjokaj said.

This ‘system’ of internships also reproduces inequality: since unpaid interns bear the costs of their ‘employment,’ not everybody can afford to work up to one year without an income. As a result, individuals entering the labor market with less financial means struggle to gather internship experiences to pad their CVs. Often they are forced to work low-skilled jobs, which unlike internships, offer hard cash in return.

“It would be great to continue my education and develop myself further. For example, to work with children with learning disabilities,” said Agron, a psychology student in his 30s who works as a security guard. “But who will pay for my rent and bread if I’m doing it for free?”

Countries like Germany, France, Spain, and Ireland already have laws that oblige employers to provide compensation for internships, although even those measures have come under scrutiny from critical activists who deem them insufficient.

While, hardly anyone disagrees that internships can be an important first step in one’s professional career, without legal measures in place to protect the labor rights of interns, such exploitation can only be expected to continue.

But at least there is room for minor improvements. Tanita’s current workplace, for example, cannot afford to pay their interns more than 80 euros per month, but they do offer contracts and mentorship, which is an incremental but necessary improvement.

“Not much effort is needed to improve this. If the tiny foundation like one that I’m currently working at can do this, others can as well,” she concluded.