Vladimir Miladinovic’s exhibition ‘Drawing Rectification’ opens at the Boxing Club on April 7. Lura Limani visits the show and discusses the ink reproductions of archival works with the artist.

“I don’t feel guilty about anything that happened in the 1990s,” Vojislav Seselj said just a week ago, adding that his idea of the Greater Serbia – a state that would include territories around Serbia inhabited by its neighbors – would remain “immortal.” Seselj was just acquitted by the Hague Tribunal on charges of crimes against humanity, murder and persecution, expulsion and torture. Neither Seselj, nor Karadzic, who was sentenced with 40 years in prison a few weeks ago, were accused of crimes in Kosovo, but their sentencing resonates in a country where 17 years after the war, 1,600 people are still missing.

In that sense, it is a strange but crucial moment to exhibit Vladimir Miladinovic’s work in Prishtina. On March 26, dozens of young activists marched from central Belgrade to Batajnica to mark the 17th anniversary of the Suhareka massacre. Like Miladinovic, the activists were adamant to not let history simply slip away: more than 700 bodies were found in a mass grave in the Belgrade suburb in 2001. Yet, this is neither part of a collective memory nor does it find a place in a public discourse which would rather forget the ‘90s as one does a bad dream.

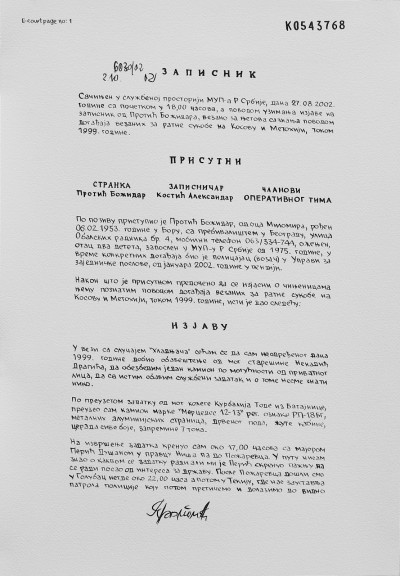

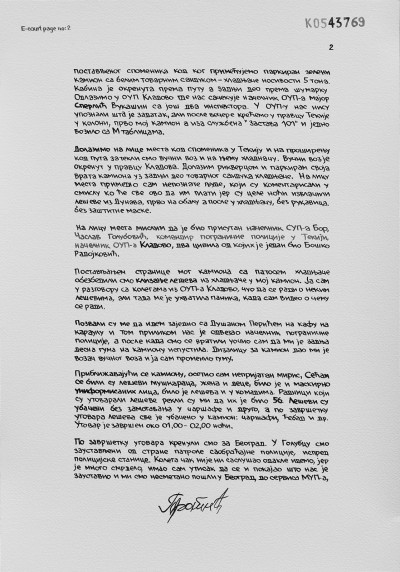

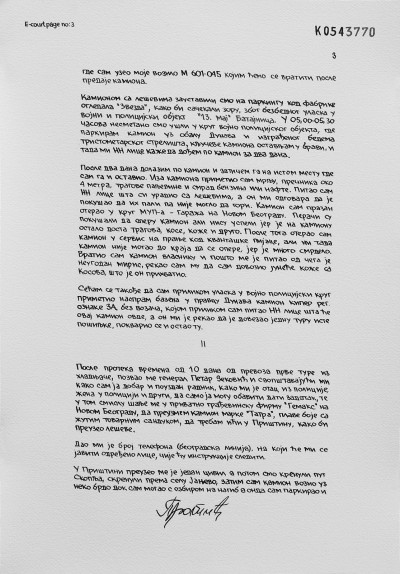

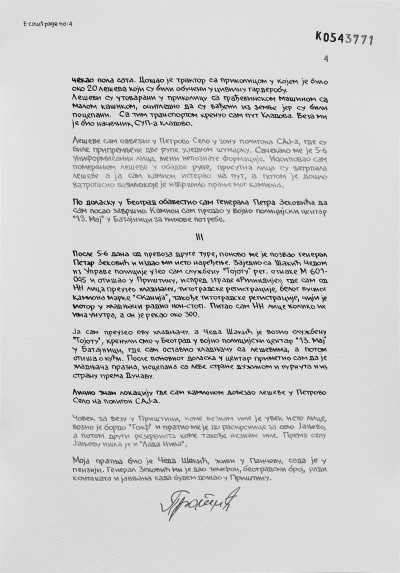

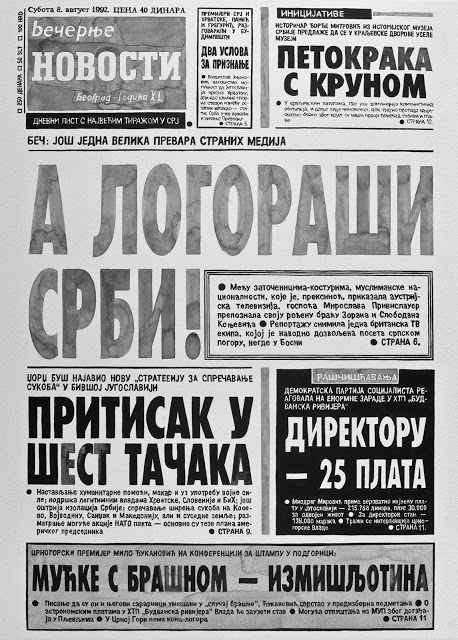

Miladinovic, a Belgrade-based artist who for the past few years has followed “a daily routine” of searching the archives and resurrecting documents from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, newspaper covers, official documents, lists, reports pertaining to the wars during the 1990s, is presenting part of his ‘Rendered History’ series at the Boxing Club, open from April 7 until May 7. Each document or piece of paper is reproduced by hand in verbatim, resulting into ink drawings of magazine covers, reports, or maps that look much like the originals, with the exception of being larger. Miladinovic does not comment the source material, he reproduces it by hand to visualize his own research and reading.

The exhibition curated by Albert Heta, the director of the Center for Contemporary Art Stacion, is a presentation of some of these reproductions, which hang on the temporarily installed white walls. The viewer strolls through the ‘sanitized’ room, which now has been turned into an archival white cube, and can read reports on concentration camps, mass graves, as well as an excavation report at the Batajnica site along with a list of items discovered next to the bodies.

Just as it is cruel to read the list of items in Miladinovic’s neat handwriting, it is equally harrowing to follow the meticulous reporting of the items. Hundreds of things are listed one after another: a Pierre Henry wrist watch is followed by hair, pubic hair, car keys, more wristwatches and metal projectiles. It is repetitive, and as Miladinovic himself says, boring and bureaucratic, but what better can illuminate the banality of evil than tedious technical language.

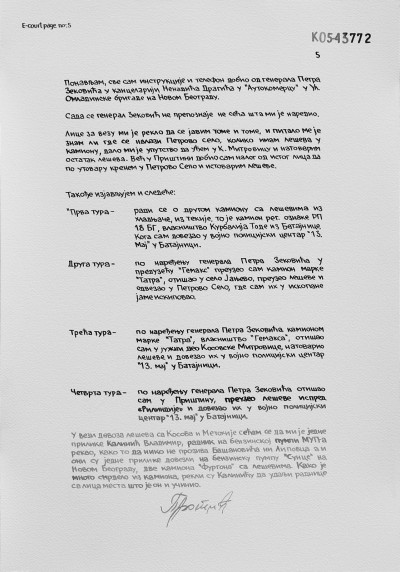

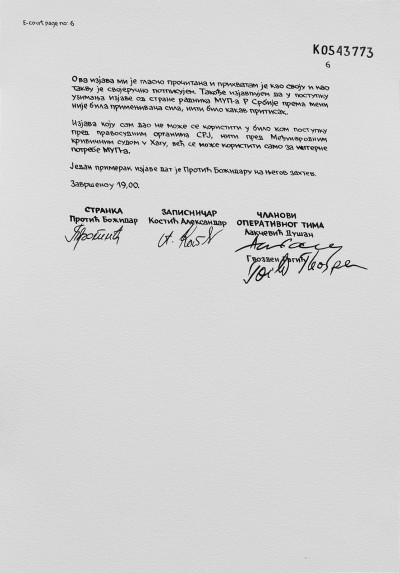

Similarly, the presentation of a six page report written by the truck driver who transported the bodies from Kosovo to Batajnica in order to “sanitize the site,” hints at the propriety of the war machine – it was after all properly documented!

"Zapisnik" (Record), 2016. Series of six drawings Ink wash on watercolor paper Dimensions 50cm x35cm. 2016.

“Batajnica is not a topic that is hidden, the state did everything about it – they discovered the bodies, prosecuted people, returned the bodies to relatives – they did the bare minimum,” explains Miladinovic, adding that the problem was not with the knowledge – the knowledge is available. Nevertheless most people need to be reminded what happened, because the memory of a mass grave just outside of Belgrade is vague. “They will say, ‘Oh yes, I know, but please remind me what was it about,’” adds Miladinovic.

As a response Miladinovic spends hours on reproducing ink documents created by a bureaucratic justice system, whose knowledge production can be questioned if it fails in being incorporated in any kind of cultural memory (cf. Assman). His reproductions, whether they are of an item list exhumed from a mass grave site by an archeology team (which he says included students), or cover pages of major newspapers revealing the existence of concentration camps in Bosnia, are interventions in these memory processes. In a sense the artworks serve as reminders, but can also be interpreted as an inquiry into memory practices. Inevitably, they are bound to questions of national identity and how it is constructed on an erasure of a certain past, as Miladinovic explains.

“The question is whether this bureaucratic agenda, the court, the law – this bureaucratic forum produces any specific knowledge,” said Miladinovic, who is using his artworks as a tool to address the problem of knowledge that is produced but remains meaningless.

In the curatorial note of the exhibition, Heta asks, “What is being drawn and washed in ink (not) to be moved and (not) hidden anymore and shown in this exhibition? What and for whom? Are all sides in one place?” I would say that the meaning the works produce depends radically from the context of their exhibition. In Serbia they relate to an audience which is aware but might not feel responsible for atrocities committed by a rabid nationalist regime, with the question of collective guilt versus collective responsibility still majorly ignored. In Kosovo, they might serve as a mock-trial: a necessary justice process which was taken away from Albanians, says Heta.

“A trial is necessary for reconciliation,” he explained on Tuesday during a public debate about art organized by New Perspektiva in cooperation Democracy for Development (D4D). Very few Serbs were tried in Kosovo for war crimes, and even relatives of the victims found in Batajnica had to testify in court in Serbia. “Crimes are usually tried where they happen,” Heta pointed out, but in general that has not been the case with Kosovo. The displacement of the trials, whether in Serbia or the Hague, robbed Albanians from a justice process which would allow for mourning, as well as closure. Reconciliation here might not mean only between people, but also reconciling with one’s past. Indeed, the war might have ended in 1999, but every new agreement in Brussels, whether with Serbia or the EU, serves as a jolt reminding Kosovars of the yet unfinished process of state-building.

By titling the exhibition ‘Drawing rectification’ the curator and the artist hint at a process of correction which is not necessarily available to memory. In the end, what would the rectification be? “The artist’s role is to challenge dominant narratives,” Miladinovic told me while showing me his work. He was anxious about the reception in Kosovo, aware that it could be used for “politics of victimization,” which he considers naive. Interested in the creative process of imagination, he explained that he was curious how these documents can be used to imagine how those things happened. But, the audience in Prishtina not only can imagine their occurrence – it can also remember it.

“Proof is necessary only for those who don’t believe,” Miladinovic told me. I would disagree – proof also serves as a reinforcement of an already known truth. Proof can also operate as an acknowledgment, which is crucial in imagining any kind of justice. Seventeen years after the Kosovo war, the Serbian government has not yet issued an official apology for the crimes committed against the Albanian population by the Milosevic regime. Miladinovic’s work, in this radically different context, might serve as another reminder that there is a large amount of knowledge produced about the war – but not much acknowledgment of its victims.

The exhibition opens on Thursday, April 7 at 8 pm, and will be open until May 7. The Boxing Club is located on Mark Isaku st. no.2, in Prishtina. Opening hours: Tue.- Frii. 11 am – 1 pm, and 3 pm – 5 pm.