Brought to the US as a nine-year-old, Albanian filmmaker Juna Skenderi potentially faces forced return to Tirana as President Trump moves to enforce stricter immigration policies.

New York –

Juna Skenderi has not stepped outside of the United States for the past 21 years. Fast-paced and bubbly, I would describe her as an ‘all American girl.’ But, Skenderi, originally from Albania, is an undocumented immigrant.

“We’ve overstayed our visa for 18 years,” Skenderi explained frankly.

Skenderi is a recipient of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, DACA, a program President Obama established with an executive order in 2012 to give undocumented people who arrived in the United States as children a pathway to attaining work and education.

President Donald Trump, who campaigned on a xenophobic platform, rescinded the program last month, and Skenderi, who has lived for most of her life in the US, might have to leave the country she calls home.

“The way that the entire rescinding of DACA happened – I would describe it as a really shitty breakup,” Skenderi told me in early September, a week after President Trump’s administration announced it would be phasing out DACA and halting new applications.

Prior to moving to the US, the Skenderi family lived in Tirana, Albania. Here, Juna (left) is posing with her sister Silva (right).

The program, signed by Obama after a series of failures to pass a bill known as the DREAM Act in Congress, offered work permits and renewable two-year protections from deportation for certain undocumented immigrants who arrived in the US before age 16. It required registering with the government and listing a home address, something that now alarms many recipients who fear that they could be easily tracked down and deported.

“By rescinding it in this ruthless way, in some obscure way it might be a good thing,” Skenderi said, adding that now that everyone is “super hyper aware and hyper-sensitive,” a solution might be possible.

After the immediate backlash to the decision, the President backtracked and gave contradictory statements: hours after his administration rescinded the program he proclaimed his love for the so-called Dreamers and gave Congress a deadline to push a bill forward by March next year. But after the White House published hardline immigration policy demands on Sunday, including the construction of a 10 billion dollar wall on the border with Mexico (a move that the Washington Post has called ‘a sabotage’), a deal to save DACA seems once again out of reach.

“By doing this, [President Trump] forced me and a lot of kids – because I feel like a kid when I talk about this – he’s forced us to live in the present,” Skenderi told me as we sipped green tea in downtown New York. “We can’t make plans.”

The term ‘Dreamer’ has been in my family for a very long time

Skenderi, a 30-year-old filmmaker who is currently working on a documentary project about being an undocumented immigrant and her family’s “failed American dream,” is impatiently waiting for Congress’ negotiations to end.

Congressional Democrats are trying to salvage the program by agreeing to The White House’s demands for stricter immigration policies, as immigrant rights activists continue to protest. In her hometown, minority leader Nancy Pelosi was also accosted by activists, who flooded the stage demanding “All of us or none of us!”

“The term ‘Dreamer’ has been in my family for a very long time,” said Skenderi, who moved with her parents and two sisters to New Jersey in 1996 when her father got a job in an American company. Not long after they arrived, Skenderi’s father, a pharmacist specializing in herbal medicine, realized that the company was going bankrupt. Once it did, he lost his job and could not renew his work permit. In April 1999, the family had two choices: go back to Tirana as the war in Kosovo was raging, or stay in the US illegally.

Skenderi as a young girl stands for a photo with her American friends.

“I found out all of this only after I was looking into applying for colleges,” explained Skenderi, who studied filmmaking at Montclair State University, working her way through college as she was not eligible for a loan (when I asked her about it she widened her eyes and said “Loans? No.” and laughed at my naivete). Her story echoes those of many DACA recipients, some of whom don’t find out about their status until they want to apply for a driver’s license or college admission.

“I feel like I’m floating above myself, I’m only able to talk about it now because I’ve been working on the film,” she confided. “I feel like a year ago, I would have only been crying.”

There are about 11 million undocumented immigrants in the US, about 800,000 of which are DACA recipients. The vast majority, 78 per cent, are from Mexico, while immigrants from Guatemala and Korea follow at five and three per cent respectively.

The problem of Dreamers and DACA is very much a deeper racial issue.

In contrast, numbers of DACA beneficiaries from the Balkans are insignificant: 250 from Albania; 70 from Macedonia; 50 from Montenegro; 30 from Serbia; 20 from Kosovo and Croatia each; and no recorded cases from Bosnia and Herzegovina or Slovenia.

While Skenderi shares much of the uncertainty and precarity of her fellow-Dreamers from across the world, as a petite blonde, she also noted that she benefits from white privilege.

“The problem of Dreamers and DACA is very much a deeper racial issue. It’s just one little branch of the giant tree that’s the race issue of this country,” Skenderi explained, emphasizing over and over again how incredibly privileged she was. When she goes to rallies, Skenderi told me, people often mistake her for an ally.

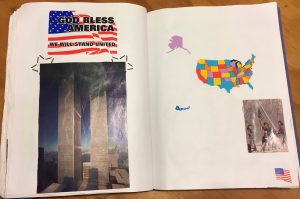

Skenderi’s childhood scrapbook, depicting images of young Juna with friends in New York.

“Whenever I go to marches, we chant in Spanish… The only Spanish I know is about resisting!” she said smiling.

Looking at pictures of Juna’s childhood and adolescence, one is struck by her coyness: posing with her two sisters and cousins in Tirana, or sitting proudly with her new toys for her tenth birthday; or (my personal favorite), sitting angelically on the grass in her cheerleader uniform. At the same time, one is struck by their conventionality. Her scrapbook looks like that of any other American pre-teen.

Most conventional, she told me while two beams of light pierced the New York sky, was her reaction to 9/11: she glued a photo of the burning Twin Towers and a ‘God Bless America’ sticker in her diary. “I’ve never felt more American in my life… that, I’m on this side of things,” she said earnestly.

Her scrapbook otherwise documents a happy childhood. Skenderi and her two sisters learned English in a year and “integrated in American society rapidly, to the point that I don’t think I had a moment to question things until later when I was in high school.”

Skenderi included the September 11 attacks in her childhood scrapbook.

Skenderi herself was popular from the start. On the first day of school she won a race, beating the tomboy, and became fast friends with the popular girls. “Being thrown into popularity… I was immediately accepted.”

It was only later, in high school, that she realized that unlike many of her friends she did not have a lot of privileges but had been “urgently accepted” because of her whiteness. In high school she also realized that she could not just tell her fellow immigrant classmates of color that “she was one of them.” She looks back at this with guilt, realizing that part of the reason she didn’t reach out as a teenager is because it would have jeopardized her status as a white, popular girl.

Skenderi’s first job was at the town library in Rutherford, when she was 16. “Because I was 16, they didn’t really ask for authorization… all I had was this slip from school which said ‘yes, you’re allowed to work,’” she said, adding that this was “the job that really paid for college, on top of the many other jobs that I did.”

After her parent’s savings ran out, her dad, who Skenderi pointedly remarked, has a PhD, delivered pizzas and worked in a gas station, while her mother babysat (“A lot of babysitting in our whole family”). Juna and her older sister also helped chip in for the rent.

Today, Juna Skenderi is a 30-year-old filmmaker and DACA recipient.

Skenderi, who always knew she wanted to be an artist, learned video production in high school and decided to study film at Montclair.

“Honestly, it was my only option, because it was a state college and I could count as an in-state student,” she said, explaining that it was her mother who had done all this research about where she could pursue higher education. It was around this time that Skenderi found out about her undocumented status.

“I don’t think I knew the depth of it. I just sort of assumed that it was like we were working towards getting our Green Cards but it was somehow more challenging for us for some reason.”

Equipped with a Social Security Number, which her parents had gotten when they still had legal permits, Skenderi was able to work odd jobs in restaurants or film sets, and pay taxes.

“I never lied [about my status]. I would say ‘All I have is a SSN; I’ve worked at my library and paid taxes.’ I also tried to get [my employers] to sympathize,” she said, adding with modesty that since she was good at her job and charming, it usually worked.

“It was ironic, because I was allowed to get in there because of my perfect English and white skin, but right in the basement and the kitchen were all kinds of undocumented people working in the kitchen who were faking their papers and doing all of those things. I never did, but I was just able to say ‘this is all I have’ and that would be good enough,” she said.

When DACA was introduced in 2012, Skenderi was relieved: she could find something more than an odd restaurant job. But being in the art world also reminded her of how much she’s missing out on. Her friends are starting to save and travel, or buy property – things that she desperately wants and cannot do.

Skenderi has not seen her family in Albania for 21 years. In this photo, Juna (far right) poses with her sisters and cousins.

Leading up to the election, Juna was terrified. Trump promised get rid off DACA on day one of his presidency. She became a recluse and started having dark thoughts. As a form of coping, she started embroidery, a craft that her mother had taught her and which she finds as a way to connect with her Albanian roots. It might be high time for Skenderi, who barely speaks any Albanian, to start practicing.

“Right now I feel anger that it’s come to this point for so many people… that it might come to it that my sister and I have to make that choice: pack up our things and leave,” she sighed. “My family still owns that tiny apartment in Albania, I have family back in Albania that will take care of me. I don’t have it as bad,” she said, trying to find a silver lining.