Amidst wranglings between government officials on one side and educational experts and the opposition on the other, Prishtina Insight presents a snapshot of the issues affecting the three educational institutions that lost their accreditation this week.

In July 2014, in the wake of the previous month’s inconclusive elections, Kosovo’s then prime minister, Hashim Thaci, expressed his pride at the opening of five new universities in which students from across Kosovo’s regions could enroll.

“Within the ‘New Mission’ [that year’s election slogan from the Democratic Party of Kosovo, PDK] we intend to invest in increasing the quality of our human resources in order for them to become competitive in a global economy that is relying on knowledge and innovation more and more everyday,” he told reporters.

Five years later, in July 2019, three of these institutions of higher education, ‘Haxhi Zeka’ University in Peja, ‘Isa Boletini’ University in Mitrovica and ‘Ukshin Hoti’ University in Prizren all lost their accreditation for the upcoming academic year, following a negative assessment by the National Quality Council, NQC.

Thaci, who is now Kosovo’s president and who masterminded the foundation of these public universities has been silent on the decision of the NQC. However, his former colleagues in the government have reacted fiercely against the scrapping of accreditation for the three public institutions, with current Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj calling the NQC “a mafia.”

The debate that has erupted this week looks set to continue, with government officials’ criticism of the NQC being met with calls from opposition parties, the international community and NGOs for the government to keep their hands out of the education system, and respect the assessment conducted by the NQC.

University troubles

The three public universities, along with three others in the cities of Ferizaj, Gjilan and Gjakova were all formed in the span of six years between 2009 and 2015, and have all since faced allegations of political interference and influence. They have also struggled with a lack of staff and allegations of imitating the programme of the University of Prishtina, as well as other flaws.

Current Minister for Education, Science and Technology, Shyqiri Bytyci, has stated that reducing the programs and profiling these universities is necessary, if they are not to be shut down completely. “They should be identified with selected programs so we do not have repetition, or attempts to imitate the University of Prishtina; especially while they cannot even achieve a good imitation of this university,” Bytyqi told BIRN in December 2018.

“I don’t want to go into why all these universities were opened, but there was no evaluation of the necessity of opening public universities… and when we do things without prior evaluation, there is a huge risk of deterioration,” he added, while insisting that he would review the work that the universities do.

The first of the regional universities was founded in 2009, when the Ukshin Hoti University in Prizren became the second public university to be established in Kosovo. Prizren’s new university began work in 2010, initially with 1,700 students, which increased to around 10,000 in 2014, according to official data.

However, despite the huge increase in the number of students, according to the latest report by the NQC, the university needs to improve its provisions.

“The university needs to modernise study programs but without the resources to boost libraries, provide access to modern journals, and increase staffing levels, this is very difficult,” the report states. “The University of Prizren is clearly in a difficult situation regarding funding.”

In December 2018, students protested against conditions at the university, as well as to highlight the need for scholarships and the dangers of political interference. This final issue has only exacerbated in recent months, as the university has faced accusations of employing party militants.

Since starting his position in 2017, Minister Bytyqi has appointed four members of the university board, including chairman Bedri Muhadri, who has openly admitted to being a member of Bytyqi’s party, the Social Democratic Initiative, NISMA.

This month, Demir Limaj, brother of NISMA leader Fatmir Limaj, was also appointed as an assistant economics professor, while the university’s recently elected new rector is also accused of having affiliations to the party.

The NQC report also finds technical issues with the institution, including that the university failed to give an exact number of students, giving different numbers in different declarations.

“In the first meeting it was mentioned that the university had approximately 6,000 students, but in the self-assessment report it was said that it had 17,000 students, while in the electronic data system there are more than 29,000 students,” it states.

Also, similarly to the reports on the other two universities that lost their accreditation, the NQC noticed negligence by the university in presenting documents in English, the language of the report.

Ukshin Hoti University was also criticized by the NQC for a lack of transparency in its public documents, an issue also highlighted by the Organization for Increasing Quality of Education, ORCA, who published a report on transparency in February this year.

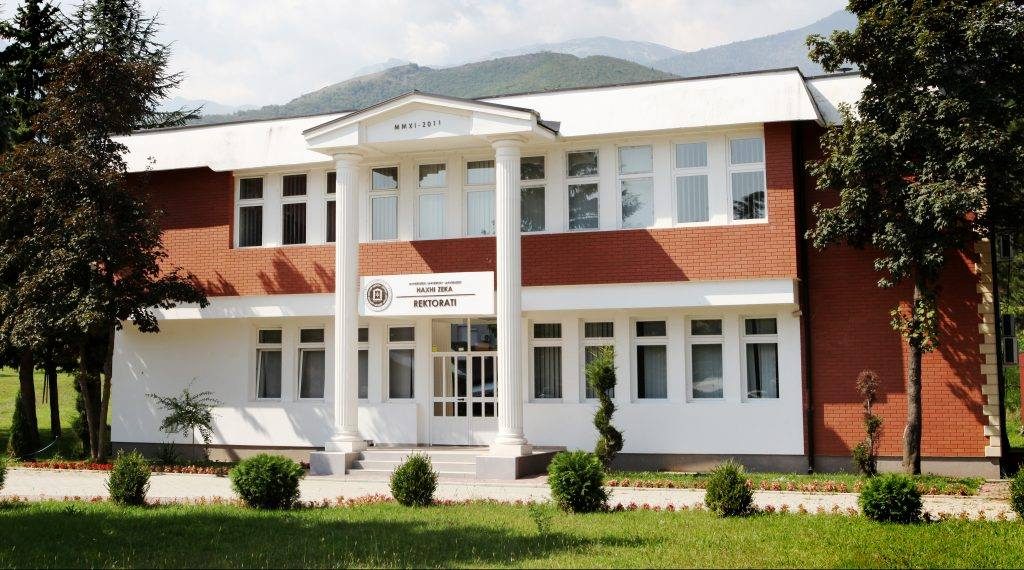

Similar challenges face the Haxhi Zeka University in Peja, established in 2011. Throughout its existence the university has faced criticism regarding nepotism and political affiliations, which were voiced in a student protest in 2017. The students also requested scholarships, for which the university said they lack the financial means.

BIRN discovered this week that a number of the academic staff at the university are members of the ruling party, PDK, which was instrumental in establishing these universities.

Astrit Ademaj, the general secretary at the university who is responsible for hiring the staff is himself a member of PDK. Contacted by BIRN on Wednesday, he responded. “Yes, I am general secretary and member of the chairmanship of PDK in Peja branch. And I am proud of it.”

The NQC report finds numerous other issues. “The administrative and managerial staff’s ability to express themselves in English is still underdeveloped,” it states. “The university’s management does not have any knowledge of the Code of Conduct and were unable to answer general questions, let alone mention specific sanctions.”

Besides problems with English, BIRN has found that the university seemingly has trouble with Albanian as well. In their official statement regarding the decision to not accredit this institution, more than ten grammatical errors were made in a three paragraph text.

According to the report, the university also had ‘no touch with reality’ regarding self-assessment. “The institution must have been preoccupied with presenting positive institutional practice and has completely failed to be self-critical,” the report says.

The Isa Boletini University in Mitrovica was formed in a package vote by the Parliament with the universities in Gjilan and Gjakova in May 2013. But while the other two public universities passed the experts’ test for accreditation, the Isa Boletini University plummeted in its recent evaluation.

In 2016, the first diploma from the university was ceremonially awarded by the President of Kosovo and the initiator for the university’s establishment, Hashim Thaci. Two years later, Thaci’s wife, Lumnije Thaci was promoted to the position of Vice-Dean.

“There was no influence [regarding my admission] because I have devoted my whole life to education and all that I have achieved, may that be little or a lot, is a hundred percent my work, my devotion,” she insisted in a statement for BIRN in 2018. She also insisted that her husband had no influence on her admission as a professor in this university prior. Before the position she lectured at the private college ‘Fama’.

Her appointment nonetheless sparked protests from the student organisation Studim, Kritike, Veprim, in which seven people were arrested.

The NQC report finds many technical issues affecting the university’s running. “There is no formal instrument for quality assurance, besides the course assessment made by the students. Teaching quality and program effectiveness is not evaluated by questionnaires or employees,” it states.

Another issue highlighted is the makeup of the university’s board. Five years after its formation, the university still functions on a temporary statute, thus giving the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, MEST, decision making powers on issues like the expulsion of a rector.

A lack of staff in this institution has caused problems in appointing management positions, and the university was criticised in the NQC report for having all of its board members appointed by MEST.

“According to the Higher Education Law in Kosovo, the Board should have 5 to 9 members,” the report states. “In this composition the number of members appointed by the ministry is specified in the statute, but it should not surpass half of the total number. According to the [university’s] statute, the board has 9 members, all of which are appointed by MEST.”

A BIRN report also shows that this university has recently approved new regulations on internal elections that allow two management positions. The university has said that this was done due to the lack of internal academic staff.

The faded proposal for university reduction

The wide ruling coalition known as PAN (PDK, AAK and Nisma) came to power after June’s elections in 2017. Early on, NISMA’s Minister for Education, Science and Technology, Shyqiri Bytyqi, surfaced the idea for ‘university reduction’, saying that the ministry would discuss plans to turn most of the public universities back into branches of the University of Prishtina.

In an interview for BIRN in January 2018, he was highly critical of the universities’ quality. MEST then sent the internal report to the parliament and government for further discussion.

In December 2018, Bytyqi repeated the need for a decision regarding the existence of these universities. “There have been two proposals, the first one is for the reduction of the number of universities transforming them into branches or campuses, and the second proposal is to have a profilisation of these universities. Profilisation should be a minimum,” said Bytyqi.

However, this calendar year no major developments towards this aim have been revealed to the public, and reducing these universities capacities have not been at the heart of the debate on higher education.

Despite Bytyqi being critical of the quality of education at these universities, he did not give his support to the NQC’s decision to remove their accreditation, describing it as ‘problematic.’ According to the minister, this is because the council’s composition is questionable.

“We had an official paper by the Anti-Corruption Agency regarding some matters that the council needed to clear up,” Bytyqi said at an urgent press conference on Monday. “In the Agency’s recommendations it is said that there are legal issues with the current composition of the council. We wanted these issues to be cleared up, and for there to be no decision making from the council until these issues are cleared up.”

At the press conference, Bytyqi also asked for the government to ‘address the issue’ of the universities’ accreditation being withdrawn.

The three universities have the right to complain against the NQC’s decision, although the Complaints Council can only return decisions for reevaluation, and cannot change the NQC’s initial decision.