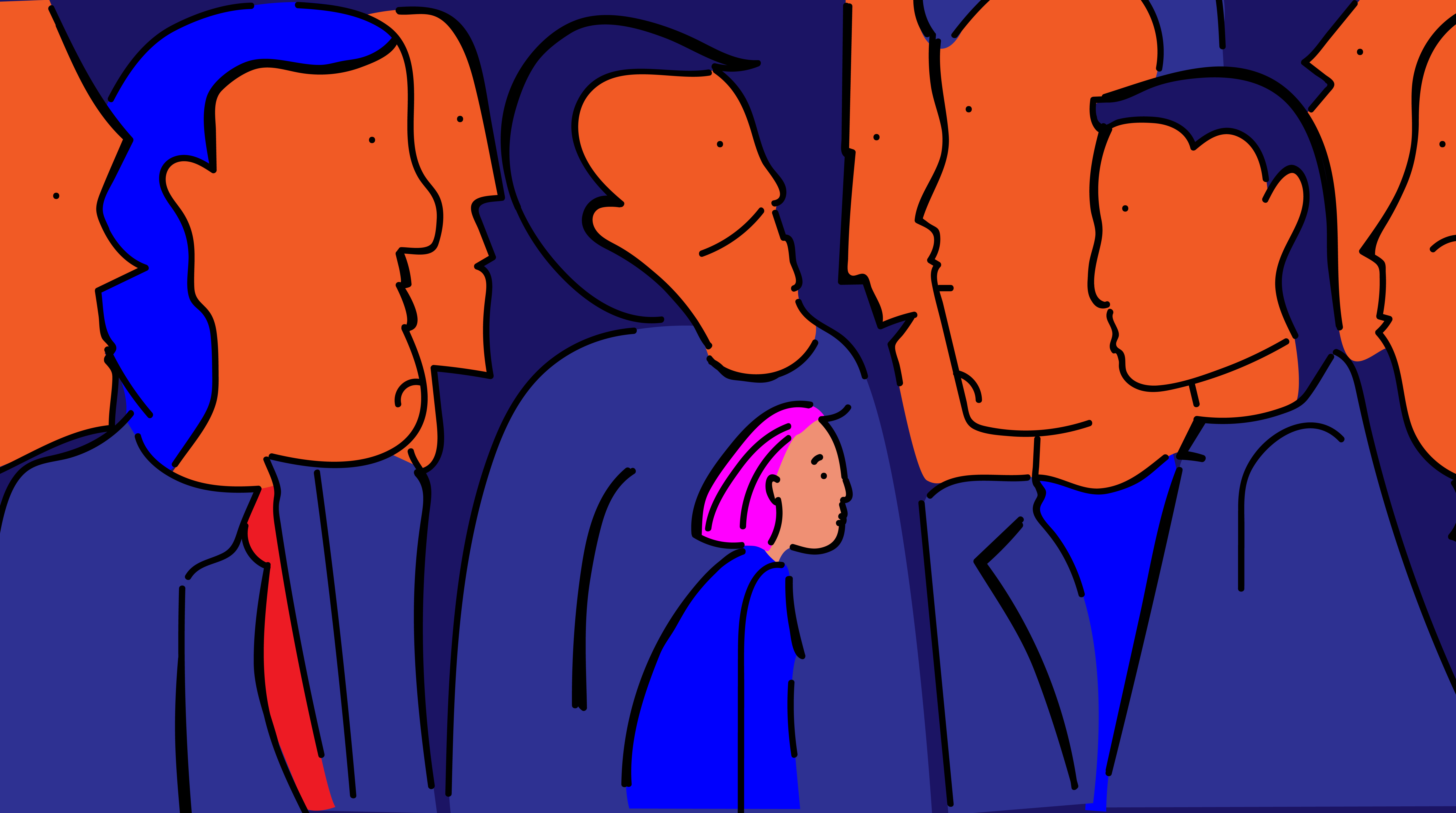

Despite quotas in place demanding equal representation, women remain vastly underrepresented in the Kosovo’s public institutions, violating the law and setting a dangerous precedent for the future.

The cabinet of the Kosovo government consists of 21 ministers, 20 men and only one woman, Dhurata Hoxha, who leads the Ministry of European Integration. Likewise, within the cabinets of these ministries, the number of women in decision making positions remains very low.

Gender equality and representation remains a challenge for Kosovo political parties as well. Only one political party, the Social Democratic Party, PSD, includes a 50 per cent gender quota in their program, a recent decision undertaken in March, making them the first party in Kosovo to adopt a self-enforced gender quota.

A study published in February by the Balkans Policy Research Group indicates that women comprise roughly 12 per cent of senior decision-making positions in the government of Kosovo. This gender disproportion is a characteristic of a patriarchal social system in a country where politics has long been considered a man’s job.

This state of affairs is a violation of the Law on Gender Equality, approved by the Kosovo Assembly in 2015.

The Law on Gender Equality obliges all public institutions to take special measures to accelerate the realization of actual gender equality.

“Equal gender representation in all legislative, executive and judicial bodies and other public institutions is achieved when a minimum representation of 50 per cent for each gender is ensured, including their governing and decision-making bodies,” reads the Law on Gender Equality.

However, the law does not specify how this should be implemented. Four years since its adoption, Kosovo institutions have failed to comply with the Law on Gender Equality, as discrimination against women remains very high.

Such a position is echoed even by members of the Kosovo Assembly, who back in 2015 voted on the law.

Albulena Haxhiu, a Vetevendosje MP, is one representative at the Kosovo Assembly whose career kicked off thanks to the gender quota in 2010. According to her, however, failures in implementation exhibit a lack of commitment from central institutions to implement the law.

“Although the law was adopted in the Assembly, it is the Assembly who is not following its own responsibilities, serving as a precedent for other institutions because lack of implementation is not being sanctioned,” said Haxhiu.

Last year, the Kosovo Assembly selected a new all-men negotiation team engaged to finalize an agreement on normalization of relations with Serbia. The negotiation team is made of nine men, politicians coming from the ruling parties and one opposition party, PSD. However, the Minister of European Integration, the only woman that serves in the cabinet, is not part of the team, despite the fact that the dialogue with Serbia would ultimately pave the way towards European integration for Kosovo.

Barriers to removing the barriers

Gender quotas were first introduced in Kosovo by the United Nations Mission in Kosovo, UNMIK. On February 17, 2008, Kosovo declared its independence, and a couple of months later adopted the law into its electoral system. A previous gender quota of 30 per cent that was adopted and implemented by UNMIK was enshrined in the Law on General Elections. This means that electoral party lists and the Assembly of Kosovo must consist of at least 30 per cent men and 30 per cent women.

Over the last couple of years, women in Kosovo have made significant advances in education, labor force participation and political activism. In fact, women have overtaken men in some areas of educational participation. However, despite improvements in education attained and political participation, this has not translated into a significant increase in women leadership in public institutions.

Only 12.7 per cent of women in Kosovo are employed, a figure that should alert us to their economic dependence. According to an OSCE survey, 55 per cent of women are dependent on the income of their partner, while 27 per cent on that of their parents.

Based on the EU Gender Action Plan 2016-2020, GAP II, the EU Office in Kosovo funded the Kosovo Gender Analysis released in 2017, which showed large inequalities and discrimination between men and women in Kosovo in the areas of law and policy.

According to the EU Office in Kosovo, lack of implementation remains the elephant in the room.

“The Kosovo Gender Analysis clearly proved that quotas have triggered improvement in women’s representation in Kosovo when applied. On the contrary, where quotas have not been applied, women remain largely underrepresented,” the EU Office said to BIRN in January.

The EU Office in Kosovo further reiterated that “women’s participation in politics is crucial for the development of inclusive, responsive, and transparent democracies. As such, the EU Office said, it is present in Kosovo to make sure local authorities adjust to such progressive practices that will eventually benefit Kosovo in the future. Ultimately, Kosovo’s perspective and goal remains EU integration; thus, ensuring women equality is a prerequisite for membership in the bloc.”

The case for quotas

Gender quotas entail that both men and women must constitute a certain percentage of the members of a certain institution. They help ensure minimal representation and reduce the socio-economic and political barriers for qualified women in Kosovo.

Quotas are usually applied as a temporary measure, until the barriers for women in access to employment opportunities are steadily decreased or removed through time.

Igballe Rogova, the head of Kosovo Women’s Network, a leading local NGO that advocates for equal rights and opportunities for women, is in principle against gender quotas. Rogova rejects the idea of seeing women as numbers. However, she stated that the current socio-economic and political situation in Kosovo makes the imposition of quotas a last resort.

“I am personally against gender quotas. However, in Kosovo it is necessary to have them because we have political leaders with patriarchal mindsets even though they proclaim they are progressive,” said Rogova.

Rogova believes that this state of affairs has societal ramifications.

“Many Kosovars believe women have specific tasks in society and a defined role,” she said. “They are not used to seeing women in leadership; thus, this constructed reality is hard to break without something solid as a counter-effect.”

Former MEP and Kosovo rapporteur in the European Parliament, Ulrike Lunacek, stated that “Kosovo needs visible women in high positions in order to encourage other girls and women to believe in that they can also have a career and earn their own money; this is also necessary to change perceptions of gender roles. Men need also to learn that women can be bosses too and that sexist language and sexual harassment are no-gos.”

For Lunacek, the contribution of former Kosovo President Atifete Jahjaga is an example of how leading women contribute to gender equality.

“President Jahjaga was quite active in the struggle against breast cancer, impunity and violence against women and served as a role model to other women and young girls in Kosovo,” she said.

The hard work begins afterwards

Albulena Haxhiu said that the implementation of the gender quota helped her establish the foundations of her political career. She managed to enter parliament in 2010 with the help of the gender quota, and since then, Haxhiu has been re-elected twice without the help of the quota.

Despite the quota helping Haxhiu overcome the barrier to election, Haxhiu believes the hard work for women in Kosovo begins afterwards. She pointed out how some local media channels contribute to damaging stereotypes against women.

“There have been cases when the secretariat of the party has sent a woman to present the Vetevendosje position on a certain issue and the latter was refused [participation] on the basis that she was not a competent person, in some cases emphasizing gender,” she explained.

For Haxhiu, women remain attacked on many other fronts in the Kosovar society.

“Even when women are part of heated TV debates, women are usually criticized for their manners, mainly using phrases such as: women should not yell, or women should be calm.”

Skeptics argue that quotas are in principle against equal opportunity since women are given preference to men. Moreover, they argue that gender quotas define elected and appointed politicians based on their gender and not on their qualifications or skills.

However, the reason why people argue for gender quotas is because their representation in senior decision-making positions is extremely low.

An effective tool to increase women’s leadership

Gender quotas do not discriminate but in fact compensate for actual barriers that women face. Studies show that having more women increases the health and quality of democratic representation.

Evidence from around the world provides examples of where quotas have had immediate and direct effect on women’s participation. According to a UN report published in 2005, quotas have been an effective tool to increase women’s access to decision-making. Moreover, they have helped boost women’s participation, decision-making and leadership and develop incentives to attract women to take leadership roles.

The government of Kosovo and its institutions should not be a place dominated by men. A government mirrors its society, a combination of different backgrounds, voices, professions and more.

Lunacek stated that a quota was always present in Kosovo, privileging men over women.

“Today an informal system of quotas is de facto in play, where men are privileged over women and where men choose men for decision-making positions, which is not a formalized system but nevertheless a systematic and very real deep-rooted culture of positive treatment of men,” she assessed.

Despite numerous challenges and problems, women role models are emerging in Kosovo society, examples such as Olympic medal winning Judoka Majlinda Kelmendi, Distria Krasniqi and Nora Gjakova are breaking the stereotypes in Kosovo.

Notwithstanding challenges, Rogova’s only hope is the young generation. She believes that new generations are more open minded and will instill a different culture which will reduce the patriarchal mindset of Kosovo society.

“The implementation of the gender quota is only the beginning of a long and problematic process of empowering women as key actors in Kosovo,” she concluded.

Visar Xhambazi is a research fellow at Prishtina Institute for Political Studies (PIPS). He holds a Master’s degree in International Studies from Old Dominion University in Virginia, specializing in US foreign policy and international relations.

Feature illustration for Prishtina Insight: Jete Dobranja/Trembelat.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Visar Xhambazi and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union or BIRN and AJK.”