Kosovo’s state budget has often been wasted on a bloated public sector wage bill and endless infrastructure projects, while social schemes have rarely reached those who need them the most or help alleviate poverty. It’s time for a change.

With snap parliamentary elections scheduled for February 14, political parties are set to spend the next month making big promises about how to improve the lives of Kosovo citizens in the coming four years.

One of the key tools for implementing parties’ electoral programs, as well as guiding political and social change, is the state budget. However, in recent years irresponsible decisions by previous Kosovo Governments have left the budget as little more than a means of cementing misguided policies.

Rather than influencing economic growth, increasing employment or alleviating poverty, a series of clientelistic governments have used the budget as a means of preserving its voter base.

The state administration is currently overloaded with employees, while social schemes are often oriented towards groups in society that have more electoral power and not towards the groups that need state support the most. At the same time, capital expenditure has mainly been concentrated on highways, which have not economically justified the astronomical costs of their construction.

Previous election promises have led to large growths in public spending, with examples include raising salaries in the public sector and installing social schemes for numerous groups affected by the political turmoil and conflicts of the 1990s – war veterans, political prisoners, as well as teachers and other members of Kosovo’s parallel system.

Every year, close to 60 percent of the state budget is devoted to wages for employees in the public sector and social transfers, while the average salary in the public sector is now 195 euros higher than the average salary in the private sector.

As salaries have increased, capital expenditure (or money spent on improving or maintaining the state’s assets) has gone down. In 2013, capital expenditure was the largest single category in the budget, accounting for 38 percent of total spending, but by 2021 it has fallen into third place, accounting for only around 26 percent.

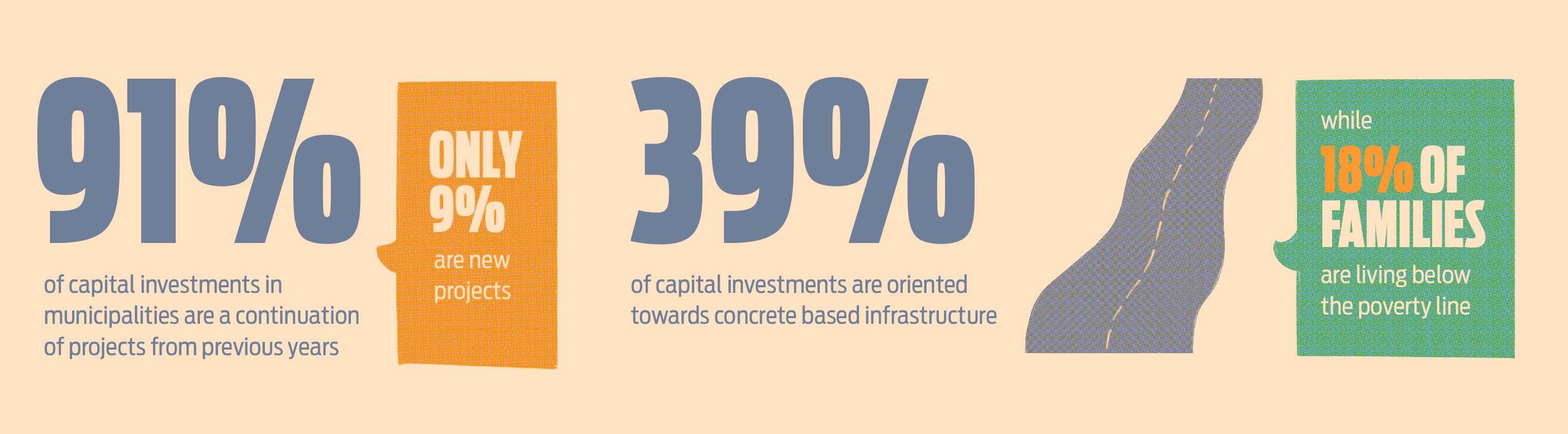

Most of that spending is also restricted due to previous decisions. In the 2021 budget, 91 percent of capital expenditure within Kosovo’s municipalities is allocated to continuations of projects from previous years, while only 9 percent or 8.5 million euros will go on new projects.

In fact, most of the 2021 budget has already been committed since 2019, when Ramush Haradinaj was Prime Minister. As a result, most of the investments are in municipalities governed by Haradinaj’s party, the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo, AAK.

All told, public spending is in a dire state of affairs, and there are four key steps that urgently need to be taken in order to restore the power of the state budget to be an effective tool of government.

First, spending on wages and expenses must be lowered, in part by reducing the number of employees in public institutions.

Currently, the 93,000 employees in the public sector make up around 30 percent of the total number of people employed in Kosovo’s formal economy. On top of this figure, an average of around 2,000 people are hired through service contracts per year.

Reducing the number of employees in the public sector does not necessarily mean dismissing people from their positions. It can also be achieved by imposing a long-term moratorium on employment and not refilling the vacant positions of those who retire.

In the next five years, 3,110 civil servants and 3,561 education workers are expected to reach retirement age. By simply not refilling these vacated positions, the number of employees in the state administration will fall significantly.

This reduction of employees in the public sector will not hinder the work of state institutions. On the contrary, it will increase efficiency and effectiveness.

For example, the number of pupils in schools has declined over the last decade. From the 2008/2009 school year up until the 2018/2019 school year the number of pupils has decreased by close to 100,000. However, the number of staff employed in schools during the same period has increased by more than 400 people.

Similarly, technological innovations have made many administrative procedures far simpler, rendering large numbers of employees in the public sector unnecessary.

The money saved on public sector salaries can then be allocated to development projects, including improving the business climate and increasing employment in the private sector.

Second, a radical reform of social schemes must be made. All of the current schemes, most of which are based on people’s role in Kosovo’s struggles during the 1990s, should be replaced by social schemes based on socio-economic status.

This means that a war veteran or a teacher in Kosovo’s parallel education system would be supported by the state through social schemes if his or her financial situation was not good, rather than simply because he or she played a crucial role in the 1990s, as current schemes are designed.

Such a reform may end up increasing the overall budget for social transfers, but it would also help reduce poverty or even eradicate it altogether if it is properly targeted. Currently, 18 percent of families are living below the poverty line, surviving on less than 1.85 euros per day.

Another demonstration of the injustice of current social policy-making is the clear gender gap. Although women make up the majority of those defined as poor, face problems in accessing housing and finance, and have a far higher rate of unemployment, around 70 percent of the recipients of social subsidies are men.

Third, capital expenditure must be redirected toward development projects and social infrastructure.

In the 2021 budget, about 39 percent of capital expenditure is oriented towards concrete based infrastructure. Meanwhile, AAK have regularly insisted on including the Dukagjini Highway project, expected to cost more than one billion euros, in any governing plan to which they are party.

However very few investments have been made that directly affect the development and social welfare of citizens in the Dukagjini region.

Fourth, in addition to spending reforms, there should be a change in approach to revenue collection.

The state has not yet managed to extend its sovereignty to the entire territory, thus leaving room for the development of informality and the so-called ‘grey economy.’ The informal economy accounts for roughly 30 percent of Kosovo’s GDP, or around 1.8 billion euros, while expanding the revenue base creates equal treatment for all businesses and increases the investment budget.

Past election campaigns have shown us that political parties do not have the courage to address issues related to public sector employment, to minimize overloaded social schemes or change the course of capital expenditure. In fact, election campaigns have only served as platforms to open the door to more problems, promising salary increases in the public sector, allocating subsidies for more and more people and pledging investments in highways.

It remains to be seen whether this election campaign will address the elephant in the room, or in this case the elephant in the budget, but here’s hoping for a change.

The views expressed in the Opinion section are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect BIRN’s views.

Agron Demi is a Senior Researcher at the GAP Institute in Prishtina.